Political engagement shouldn’t be a question of class. A new project is examining the gap and what to do about it

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 4 June 2020

4 June 2020

Social mobility is a widely shared ideal in practically all western countries: your family background should not matter for your education, your professional career and for where you end up in life. Consequently, social mobility has been a key concern of social scientists for decades – an interest reignited by the way the Covid crisis is fuelling inequalities in health, education, and the labour market.

Far fewer academics have been interested in the influence of family background on political engagement – i.e. interest in politics and the desire to participate in it. This is surprising as a lack of inter-generational ‘political’ mobility is likely to be as detrimental to social cohesion as a rigid class society. Democratically-elected governments are more incentivised to serve the interests of those who vote than those who are politically disengaged. Since middle class people have higher levels of political engagement, this may contribute to a vicious circle in which people from disadvantaged backgrounds withdraw their support for democracy altogether. In other words, the passing down of disengagement across generatations may lead to a permanent and alienated ‘political’ underclass.

This is why the Nuffield Foundation has funded our project, entitled “Post-16 Educational Trajectories and Social Inequalities in Political Engagement” (April 2020 to September 2021), which aims to investigate:

- how social disparities in political engagement evolve over the life course;

- how strong the influence of post-16 educational pathways is on these disparities compared to that of earlier educational experiences and other conditions;

- whether these trajectories have lasting effects on political engagement

How can education disrupt the transmission of disengagement from one generation to the next? This is a legitimate question to ask because people develop political identities in adolescence and are therefore susceptible to external influences during this period, such as the teaching they get at school. It is a particularly pertinent question for the UK as the link between social class origin and voting is stronger in the UK than in any other European country, as I show in my recently published book co-authored with Bryony Hoskins. We also found that this link becomes stronger during adolescence, which suggests that education is actually playing a counterproductive role by increasing rather than mitigating social disparities in political engagement. It does so by sending teenagers off into different educational pathways after age 16: those from disadvantaged backgrounds are disproportionately enrolled in vocational tracks where they do not receive the same engaging education in terms of sparking an interest in politics as their peers doing A levels.

Therefore, we could potentially make a big difference by ensuring that students in the vocational track experience at least as many, if not more, relevant civic learning opportunities as those pursuing A-levels and going on to university. In fact, studies from various countries have shown that students from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit more from citizenship education than students from privileged families, in terms of becoming more politically engaged. As these young people are overrepresented in vocational studies, offering such learning opportunities in vocational education is likely to be particularly effective.

In our project, we hope to gather more evidence on these issues. We will analyse longitudinal data of the British Household Panel Survey/ Understanding Society (BHPS/US) to explore these questions. This dataset tracks multiple birth cohorts from 1991 to the present and surveys each cohort annually. It includes many questions on political engagement, education and family background. These qualities make it uniquely suited to examine the development of political engagement over the life course and the impact of education on it relative to that of other conditions.

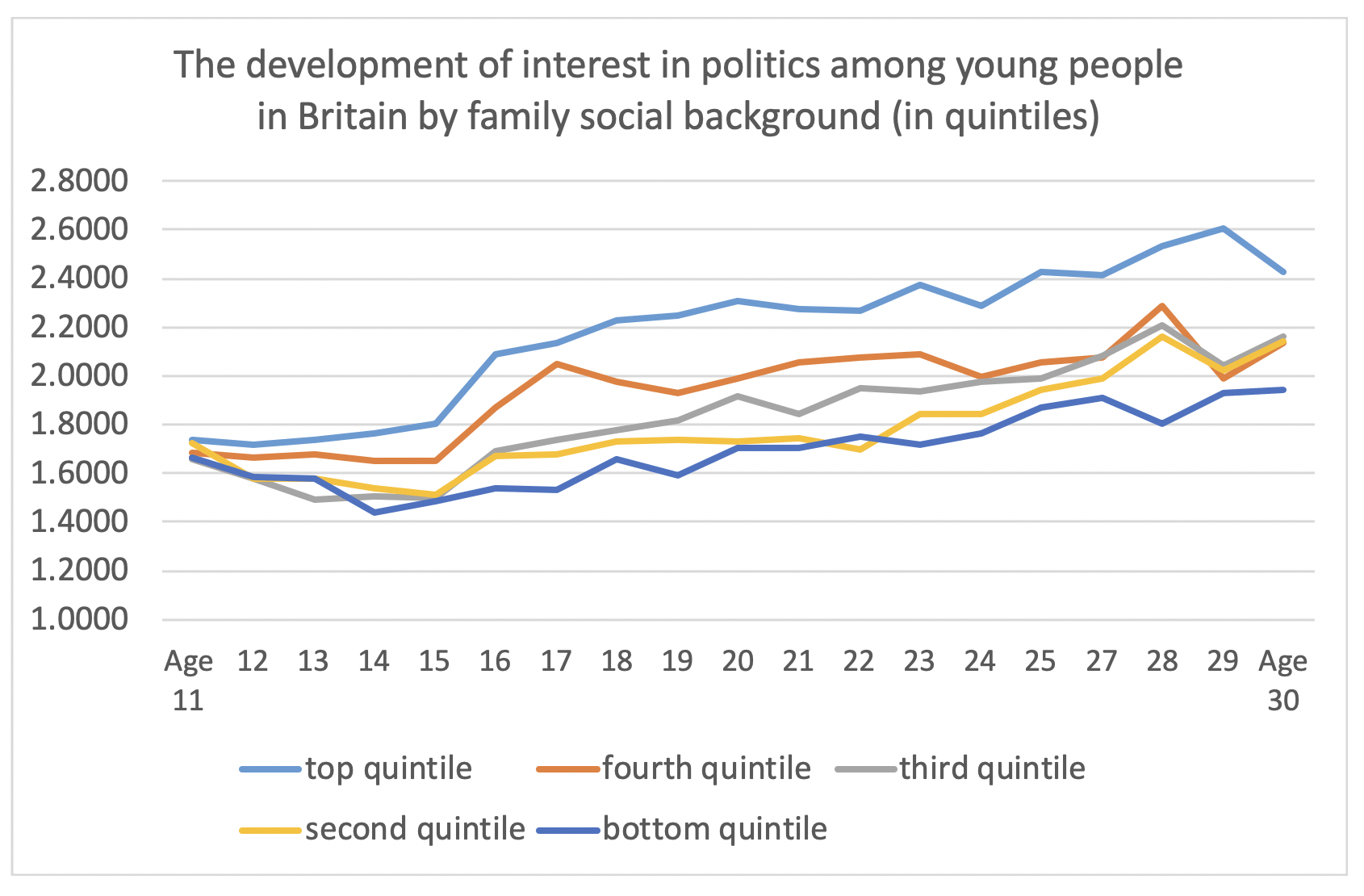

Work for the project has just started and we can already present some provisional results. The figure below shows the development of interest in politics among young people between ages 11 and 30 by social background – as measured with parental education, occupation and income. Social background is given in quintiles – bottom 20%, 20-40%, 40-60%, 60-80% and top 20% – and political interest is captured with a four point Likert scale ranging between 1= “not at all interested” and 4= “very interested”. The midpoint of this scale is 2.5, which indicates neither interest nor the lack of it. The lines in the figure represent the average political interest for each quintile. We see that children from different social backgrounds hardly differ in their interest in politics at age 11. All score well below the mid-point of the scale, indicating broad disinterest. However, differences soon emerge and by age 15 there is a clear relation with social background: children from the top 20% are the most interested in politics and those from the bottom 20% the least. After age 15 levels of interest rise for every group but they rise much faster for children from privileged backgrounds than they do for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This clear divergence coincides with the branching out of the education system in several tracks. Thus, these provisional findings are in agreement with the ones mentioned earlier. The next step in our analysis is to see whether the branching out into different tracks is also causing these disparities to widen.

More information about the project is available here. The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org

Source: British Household Panel Survey/ Understanding Society

3 Responses to “Political engagement shouldn’t be a question of class. A new project is examining the gap and what to do about it”

- 1

-

2

Jan Germen Janmaat wrote on 17 June 2020:

Dear Geraldine,

Many thanks for your positive reply. I’ll certainly read your book and suggest it to a student of mine who is currently writing her dissertation on student voice and school councils.

Can I include you on the project’s mailing list?Best, Jan Germen

-

3

Geraldine Rowe wrote on 9 November 2020:

Hi Jan,

Sorry to have missed your response to my comment. Is there a chance you might like to request an inspection copy to consider as course reading, or to write a review? If so, requests can be made at http://pages.email.taylorandfrancis.com/review-copy-request quoting title ‘It’s Our School, It’s Our Time’by Geraldine Rowe ISBN 9781003015864. Pre-orders are being taken and the book will be shipped on 24/11/20.Best wishes,

Geraldine

Close

Close

I have written a book, to be published by Routledge, It’s Our School, It’s Our Time, to help schools to involve pupils in decisions that affect them. By involving pupils in decisions about the curriculum, discipline, environmental design and school culture, schools can develop a sense of agency and community involvement which has been linked By research to positive outcomes as adults (see Marmot report recommendations, for example) although research on the impact of such participation on later Voting behaviours is sparse. I wrote this book in response to the findings of my doctoral research at UCL Institute of Education. Very interested to see outcomes of your project.