Four reasons why female teachers are paid less than men

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 21 June 2018

21 June 2018

The teaching profession in England remains dominated by women, but as they accumulate experience in the classroom their pay gradually falls behind that of men. By the time secondary school teachers have accumulated 20 years of experience, men are earning almost £50,000 per annum yet women are earning under £45,000 per annum. In the primary phase the gap is larger, with men earning over £51,000 compared to women at just below £43,000. Data from seven years of the School Workforce Census, combined with a survey of over 2,000 teachers via the Teacher Tapp survey app provides some explanations for how this pay gap occurs.

1. Female teachers are less likely to reach leadership positions

Only a minority of teachers ever proceed to senior leadership positions. For example, in School Workforce Census in November 2016, for those with over 30 years of experience, 67% of men and 74% of women are still classroom teachers. However, as the chart below shows, men do make it into senior leadership posts at much higher rates than women.

2. Men make it to leadership positions much earlier in their career

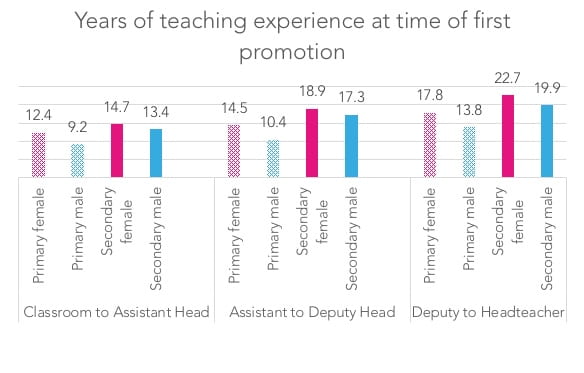

For those women who do decide to apply for senior leadership posts, their appointments tend to come much later in their career. Here we track three groups of teachers who are achieving their first promotions in the summer of 2011, and watch what happens to them during the next five years of their career. They are those who are:

- (Full-time) classroom teachers in November 2010 and (full-time) Assistant Heads by November 2011

- (Full-time) Assistant Heads in November 2010 and (full-time) Deputy Heads by November 2011

- (Full-time) Deputy Heads in November 2010 and (full-time) Headteachers by November 2011

The chart below shows that for each of these three cohorts, the men have far fewer years of experience than their counterparts when they achieve a promotion into a new senior leadership role.

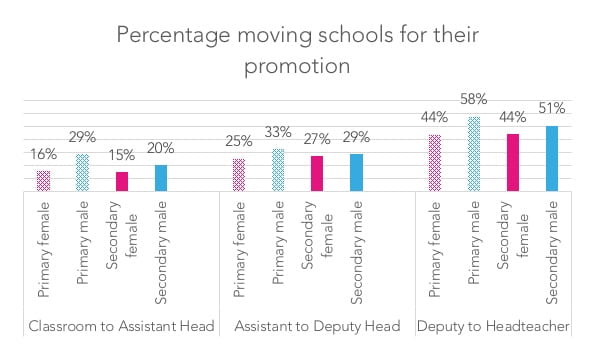

One explanatory factor seems to be male teachers’ willingness to move schools for the promotion. It seems likely (though we cannot tell here) that they are proactively seeking out promotions in new schools rather than awaiting a vacancy in their existing school.

3. Women achieve less good wages at promotion to headship

We can observe no differences in salaries achieved on first promotion to Assistant Head or Deputy Head, once we control for phase, region, age, experience and tenure in school. However, there are differences in initial wage achieved as a newly-appointed Headteacher, with male teachers achieving a £1000 greater salary, after taking account of phase, region, age, experience and tenure in school.

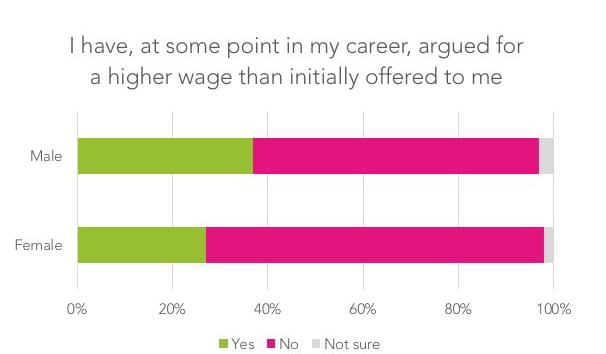

We cannot observe the wage bargaining process in the School Workforce Census, but last week we asked a sample of over 2000 teachers in English schools about their attitudes to pay negotiation. Male respondents were 10 percentage points more likely to report that they have in the past argued for a higher wage than was initially offered to them.

Teacher Tapp survey date 13/06/18; N=2,307

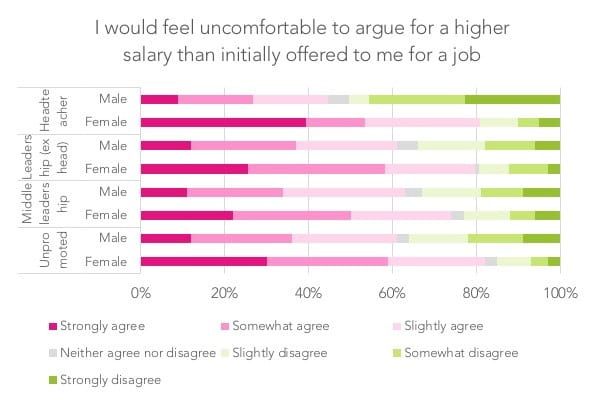

Moreover, when we asked whether the teacher would feel uncomfortable arguing for a higher salary than initially offered, women were much more likely to say that they were and this unwillingness to wage-bargain was highly pronounced amongst those who are headteachers. This is precisely the group where the pay scales allow considerable discretion in earnings.

Teacher Tapp survey date 12/06/18; N=2,348

4. Women are more likely to slip back into more junior roles after achieving promotion

As we track what happens to these three cohorts achieving their first promotions to new posts, we find their roles five years later are quite different. In each case, the women are much less likely to have secured a further promotion, are more likely to have slipped back into a lower teaching post and are more likely to be no longer teaching in a state-funded school. This has a significant impact on the wage gap between male and female teachers.

Conclusion

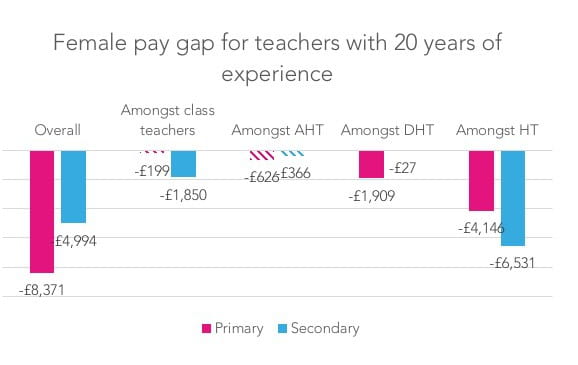

The pay gap for teachers by the time they have accumulated 20 years of experience is considerable, at over £8,000 in the primary phase and £5,000 in the secondary phase. In part, this is explained by men achieving promotions to senior leadership much earlier in their career and then being far less likely to drop out or back down to a classroom position. When we compare those with 20 years of experience by seniority, we find a pay gap amongst classroom teachers in secondary schools, most likely because the men have taken on more responsibilities that attract pay increments. We find no pay difference amongst Assistant Heads, a modest pay gap amongst Deputy Heads and a large pay gap for Heads. Given the greater discretion in pay bargaining for these more senior posts, it is worth reviewing whether this process disadvantages female teachers who report they feel less able to advocate for a higher wage.

Close

Close