These techniques, which collectively have come to be known as “Human Resource Management” (HRM), have yet to be fully tried and tested in the public sector. Initial findings are mixed. For instance, one study on the use of performance pay found it was negatively associated with the performance of public sector workplaces. However, some studies suggest HRM is generally associated with improved school performance.

Perhaps the best known study finds that, across the globe, the more intensively these practices are deployed, the better schools perform. What is currently lacking is some understanding of what works in schools, compared to what works elsewhere in the economy. Is it really the case that HRM practices have the same returns in schools as they do elsewhere in the economy?

This taps into an old argument among management scholars, some of whom subscribe to the universalist argument – these practices deliver benefits for all, regardless of circumstance – versus those who emphasise the importance of selecting practices that “fit” with the internal and external factors affecting the workplace’s performance, such as the market it operates in. Evidence on incentive pay suggests what works in the private sector may not work in the public sector. Could it be that “what works” for schools really differs from what works in the commercial for-profit sector?

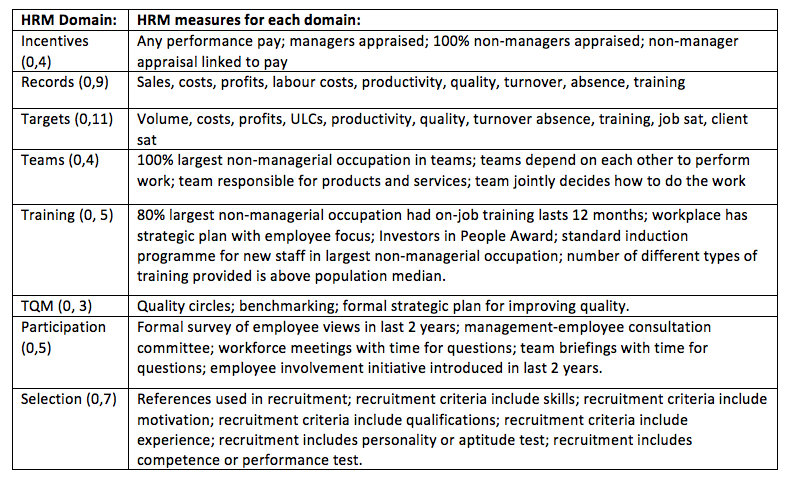

Ours is the first study to investigate whether “what works” in schools is the same or different to what usually works elsewhere. The study differs from the literature in many respects. It is, to our knowledge, the first to compare schools with other workplaces – the rest of the literature is confined to the schools’ sector. In doing so, it draws on nationally representative surveys of workplaces in Britain in 2004 and 2011. These data contain 48 measures of HRM (see the table below), increasing confidence in our ability to “map” the whole HRM terrain, rather than relying on a small set of practices which happen to be collected in the survey, a problem that besets many studies.

The HR managers are the survey respondents: they are the ones who know most about the practices deployed at the workplace, limiting measurement error in describing the HRM practices present at the workplace. In schools the person responsible for HR might be the Head Teacher in smaller schools or, in large schools, a dedicated HR practitioner. We establish “what works” for eight workplace performance outcomes that are meaningful in schools and elsewhere, such as labour productivity, sickness absence and quits. Although we do not claim to identify causal linkages between HRM and workplace performance, we use a variety of statistical techniques to test the robustness of our results.

Table 1. HRM measures used in the study (click to enlarge)

We find more intensive HRM use is positively associated with better workplace financial performance and labour productivity in schools and in other “like” workplaces (they are matched on size, age, and workforce composition). When we look within workplaces over time, we also find workplace financial performance and labour productivity rise as workplaces deploy HRM more intensively.

But the types of HRM that “work” in schools differ from the types that work elsewhere.

Schools benefit from increased use of rigorous hiring practices when selecting new recruits, employee participation mechanisms (such as team briefings), total quality management (TQM) and careful record-keeping, none of which seem to improve workplace performance elsewhere in the economy. By contrast, increased use of performance-related pay and performance monitoring, which do improve workplace performance elsewhere in the economy, are ineffective in schools. The only HRM practice that benefits both schools and other workplaces is more intensive provision of training.

The findings are important for government policy. Head Teachers have increasing autonomy over managerial decisions, not only in Academies, where they are no longer local government-controlled, but across the whole schools’ sector, so it’s important that they understand how to use that autonomy when adopting HRM. We find HRM is linked to improvements in schools’ financial performance, something that’s vital given the parlous state of many schools’ finances. But it does little to tackle teacher turnover, something that is of increasing concern. Our findings also raise concerns about the government’s hopes that greater use of performance pay for teachers will bring about improvements in school performance. The challenge for schools and government is to experiment with HRM to work out what works in a school context, then disseminate that across the sector to raise schools’ performance everywhere.

Author notes:

The study uses the Workplace Employment Relations Surveys for 2004 and 2011. These are nationally representative surveys of workplaces with five or more employees. They contain 406 schools (226 primary, 129 secondary and 51 technical/vocational). The non-schools workplaces comprise 3,485 private sector workplaces and 1,084 public sector workplaces. Panel analyses are conducted on the subset of workplaces followed up between 2004 and 2011, which includes 87 schools. The analyses are weighted so that estimates can be generalised from the sample to the population as a whole. The workplace performance measure is based on managerial responses to three questions: ‘Compared to other workplaces in the same industry how would you assess your workplace’s… financial performance, labour productivity, quality of product or service?’ Each is scored on a scale running from ‘a lot below average’ to ‘a lot above average’. The scales are collapsed into an additive (0,9) scale where 9 identifies the best performers. We use a variety of estimation techniques to investigate links between HRM and workplace performance including Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression; weighted regressions using propensity scores; weighted regressions using entropy balancing; and panel analyses.

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper Can HRM Improve Schools’ Performance?, which is being presented at the Royal Economic Society’s 2018 Annual Conference, at the University of Sussex, Brighton.

- Acknowledgements: The researchers acknowledge the Nuffield Foundation for funding this study (grant number grant EDU/41926), the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service and the National Institute of Economic and Social Research as the originators of the Workplace Employee Relations Survey data, and the Data Archive at the University of Essex as the distributor of the data. All errors and omissions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

- The post gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE Business Review, the London School of Economics or the IOE.

Close

Close

Thanks Jan useful

Anna Douglas

>