Jerome Bruner: ‘A life is a work of art, probably the greatest one we produce’

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 13 July 2016

13 July 2016

Jerome Bruner, one of the most influential writers of our times in the fields of psychology, culture and education died aged 100 on June 5 2016. His writing scored much more than a century: it set up enduring understandings about humanity.

His dynamic development started with psychology but became more extensive and more integrated, especially with the concept of narrative, and his own story illustrates the ideas and understandings as they developed.

He was born on October 1 1915 in New York City to Herman and Rose Bruner, Polish Jewish immigrants. I hesitate to mention that because Jerry’s research (1957) demonstrated that an introduction with such categories leads our perceptions to continue focusing on them. Jerry never smoothly fitted other people’s categories. He was born blind and didn’t have sight until the age of two. I do not hesitate to mention that because Jerry has helped us see so much. And he said “having my sight restored, made me sensitive to the new”. His father died when he was 12, and his mother moved around the USA. After a secondary school experience in six high schools which he described as “appalling”, he went to college (1933) and quickly achieved first degree (1937), MA (1939) and PhD (1941).

His first publications from his first degree reflected the dominant fashion in psychology at the time: experiments with rats. But he showed that shock treatment could affect future learning. And Jerry crossed other boundaries: he said last year “When I had a particularly bright rat, I would take the rat home and give it to my children, and they’d become my children’s pets around house. So they weren’t just laboratory animals”. Similarly humans were not to be regarded just as simple responders to stimulus, but as creators. In 1939 he began his postgraduate study at Harvard, where he was soon working on an analysis of the previous 50 years of American psychology, differentiating psychology for science’s sake from psychology for society’s sake.

World War II intervened: he worked in military intelligence analysing German propaganda broadcasts: “I’d got myself into the job because I’d been turned down for the draft but that wasn’t going to stop me”. His doctoral thesis in 1941 was entitled “A Psychological Analysis of International Radio Broadcasts of Belligerent Nations” and led to analytic publications on conflict and propaganda and his first book (1944) Mandate from the People. It was important to him tackling the dynamics of division and democracy in a new international context .

After the war he returned to Harvard saying “This was the place where the future of psychology was being shaped”. His research demonstrated that human perception was influenced by matters of value, as when 10-year-olds judged high value coins to be 35% larger than cardboard discs of the same size. For children from low-income households the effect was larger. So our perception of the world is not a matter of accuracy. From there it followed that “knowing” was how human beings get “beyond the information given”. “I guess my view is that knowing, getting to know the world, is not just perceiving something; it’s constructing it”.

In 1952 he became professor of psychology. His book A Study of Thinking (1956) portrayed human beings as strategic learners who work hard to make sense of the world around them. A later emphasis of Bruner’s stance was that “to gain insight requires ‘going meta’ … that enables you to turn around on yourself, to reflect upon your reflections”.

Following the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957 a conference was held to identify the problems of science education and to recommend solutions. Bruner chaired it, and later published The Process of Education (1960) which emphasised the importance of initiative and motivation to learn. Learning is an active process in which learners construct new ideas or concepts. The learner selects and transforms information, constructs hypotheses, and makes decisions. “We concluded that any subject could be taught in some honest form to any child at any stage in his development.” This was a landmark book which led to much experimentation and a broad range of educational programs in the 1960s. It has been translated into nineteen languages and has sold more than 500,000 copies. “I confess that the book’s initial reception and the widespread comment it produced surprised me”. His later book Toward a Theory of Instruction (1966) emphasised three elements of learner-centred education: stimulate curiosity, develop competence, build community. He also tackled the detail of curriculum development in Man: A Course Of Study 1965. Films and other audio-visual materials were created to support enquiries around three themes: What is human about human beings? How did they get that way? How can they be made more so? This made him no stranger to how politics were starting to control education: “we found ourselves handily defeated in distributing MACOS to American schools by fierce opposition sparked by the then Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, who actively opposed its adoption in his home State”. He was more successful in 1965 under the Lyndon Johnson government, establishing the Head Start pre-school provision.

In the early 1970s Bruner found Harvard conservative and took up an invitation to join the University of Oxford. He liked to tell the story of crossing the Atlantic in his classic yawl “Wester Till”. A landfall in West Cork, led to his getaway (and writing) cottage in Reenogreena.

At Oxford the focus on early years continued with the PreSchool Research Group “That was taken up by Lady Plowden in her battles with the then minister for education, Margaret Thatcher”. But there was considerable disagreement with the experimental psychologists at Oxford, and he returned to Harvard in 1979.

The 1980s brought the “narrative turn”, where Jerry highlighted thinking, self-knowledge and culture as the human use of story. His book Actual Minds, Possible Worlds has 14,000 citations. And having earlier clarified that one of the unique properties of humans is their ability to think about their thinking, and learn about their learning he later (1998) published on humans’ stories about their stories. “Typically we tell ourselves about our own Self and about other Selves in the form of a story”. At age 84 Jerry published on narratives of aging. “A life is a work of art, probably the greatest one we produce”. Most recently he analysed processes of law from this perspective.

His approach to developing ideas was explicit and engaging in his writing and lecturing. For example “Life as narrative” (1987) started with “I would like to try out an idea that may not be quite ready, indeed may not be quite possible. But I have no doubt it is worth a try. It has to do with the nature of thought”. More recently at an Oxford event which included naming a building after him, the 92-year-old steps lightly onto the platform of a crowded lecture theatre, and begins “This afternoon, I’d like to try out another idea for the future”.

In the 1990s Jerry identified worrying trends. In Acts of Meaning he argued that the ‘cognitive revolution’ had now gone wrong because it moved from the image of humans as ‘meaning-makers’ to that of ‘information-processors’, and that led psychology away from the deeper objective of understanding mind as a creator of meanings. In Culture of Education he said “education is not an island, but part of the continent of culture”. And he analysed “folk pedagogy”, the stereotypical ideas about how learning happens, many of which are active today, including in the acts of politicians. “Debates have been so focused on performance and standards that they have mostly overlooked the means by which teachers and pupils alike go about their business in real-life classrooms — how teachers teach and how pupils learn”. He visited progressive classrooms,

and analysed four crucial ideas: agency, reflection, collaboration, and culture.

I had contact with Jerry (as anyone who met him soon knew him as) at meetings to talk about learning – and life. Reaching 100 was “nifty”: in a recent email Jerry said “I find it both enlivening and thought provoking”.

At each stage his perspective became richer and more comprehensive. Some say Jerry was also a trailblazing figure in a multitude of other fields. But Bruner’s stance offers meaningful connection between those fields. Those who best understand him have described his “deeply consecutive career”. He has been influential across the world and has nearly half a million mentions on the internet.

It’s a story of a wonderful human being who knew that what is wonderful about human beings is their storying. The story will continue, but from this point on Jerry is immortal.

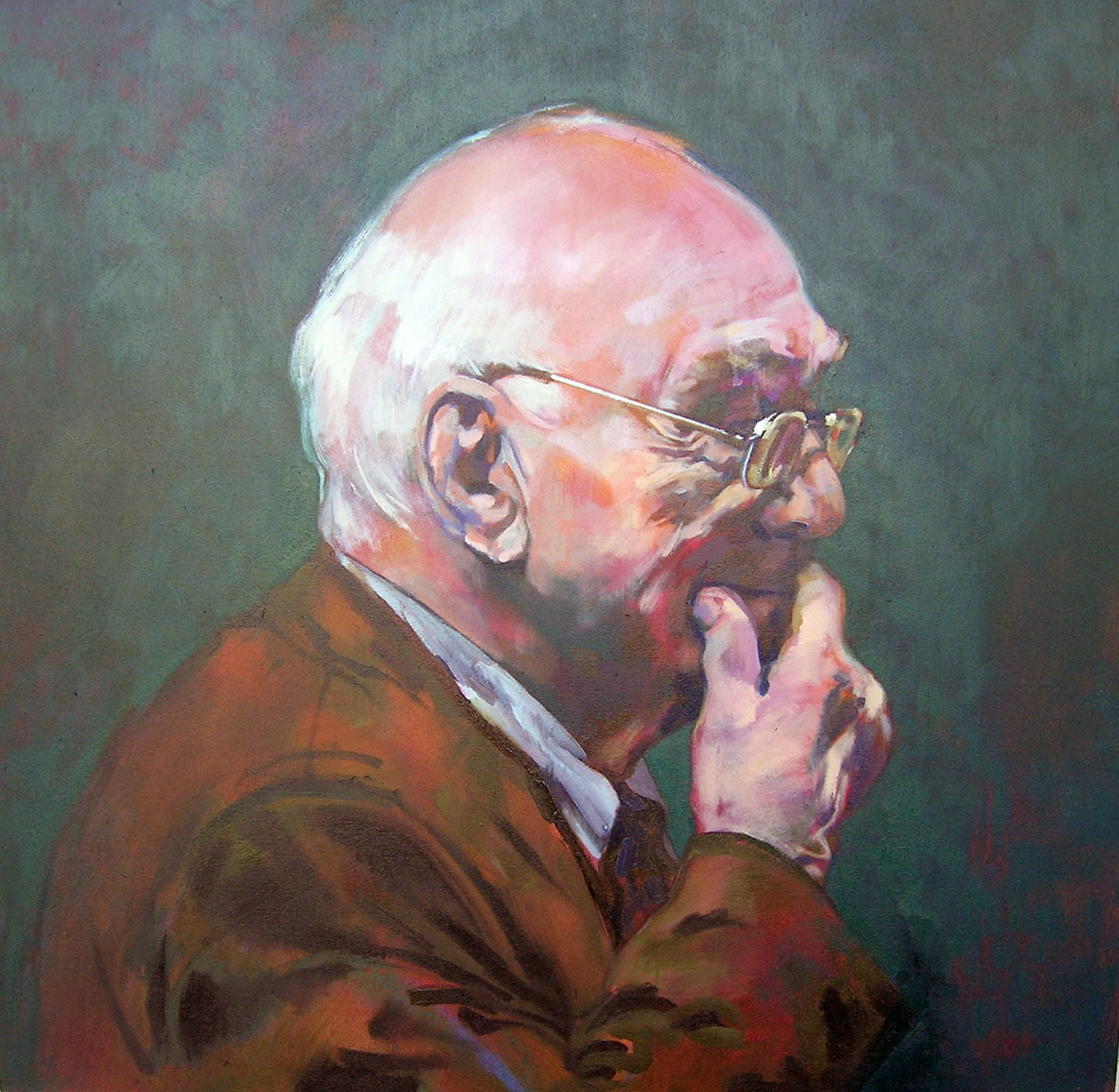

Portrait at University of Oxford by Beth Marsden 2007

2 Responses to “Jerome Bruner: ‘A life is a work of art, probably the greatest one we produce’”

- 1

-

2

lofalearner wrote on 26 July 2016:

pdf version including video links available at

http://chriswatkins.net/download/989/

Close

Close

References (in order mentioned – not all mentions are full citations)

Bruner, J. S., & Perlmutter, H. V. (1957). “Compatriot and foreigner: a study of impression formation in three countries”. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 55(2), 253.

McCulloch, T. L., & Bruner, J. S. (1939). “The effect of electric shock upon subsequent learning in the rat”. The Journal of psychology, 7(2), 333-336.

Bruner, J. S., & Allport, G. W. (1940). “Fifty years of change in American psychology”. Psychological Bulletin, 37(10), 757.

Bruner, J. S. (1943). Public thinking on post-war problems. Washington,: National planning association.

Bruner, J. S. (1944). Mandate from the people. New York,: Duell.

Bruner, J. S., & Goodman, C. C. (1947). “Value and need as organizing factors in perception”. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42, 33-44.

Bruner, J. S., Goodnow, J. J., & Austin, G. A. (1956). A study of thinking. New York ; London: Wiley.

Bruner, J. S. (1984). “Notes on the cognitive revolution – OISE’s Center for Applied Cognitive Science”. Interchange, 15(3), 1-8.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The Process of Education. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a Theory of Instruction. Cambridge MA: Belknap Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1965). Man; a course of study. Occasional paper no 3, the social studies curriculum program. Cambridge, Mass.: Educational Services.

Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (The Jerusalem-Harvard lectures). Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J., & Kalmar, D. A. (1998). Narrative and metanarrative in the construction of self. In M. D. Ferrari & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Self-awareness: Its nature and development (pp. 308-331). New York: Guildford Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1999). “Narratives of aging”. Journal of Aging Studies 13(1), 7-9

Bruner, J. S. (2003). Making stories : law, literature, life. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1987). “Life as narrative”. Social Research, 54(1), 11-32.

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

And of course don’t forget Jerry’s story of Jerry

Bruner, J. S. (1983). In search of mind : essays in autobiography (1st ed.). New York Harper & Row.