By guest blogger, on 17 January 2020

Mental illness is a major cause of early retirement – but do those who are forced to leave work early for this reason get better afterwards? What is the relationship between work stress and mental health? A new study of public sector workers in Finland suggests there is a link – and there are important lessons for employers. Tarani Chandola from the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies was among the authors of the study.

Mental illness is a major cause of early retirement – but do those who are forced to leave work early for this reason get better afterwards? What is the relationship between work stress and mental health? A new study of public sector workers in Finland suggests there is a link – and there are important lessons for employers. Tarani Chandola from the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies was among the authors of the study.

One way in which we can track the prevalence and level of mental illness is by looking at the use of psychotropic medication – that is, medication which can alter one’s mental state. This group of drugs includes common antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs and antipsychotic medication.

If there is a link between work stress and mental illness, then we should expect those forced to leave work for this reason to get better after retirement. So by tracking the levels of psychotropic medication among a group of workers before and after retirement, we could find out the extent to which there was such a link.

We were able to use data from a long-term study of Finnish public sector workers to examine the issue more closely.

It matters because previous studies have shown an increase in the use of this group of drugs among all those who take disability retirement, particularly those whose retirement was due to mental ill health. Those from higher social classes saw the biggest drop in medication use after retirement, suggesting there are social factors at play here, too.

Global issues

The effect does seem to vary around the globe, though – some studies from Asia found an increase, rather than a decrease, in mental health problems after leaving work. But in Europe, retirement has often been found to be followed by an improvement in both mental and physical health. Retirees have reported sleeping better, feeling less tired and generally feeling a greater sense of wellbeing.

We were able to use data from the Finnish Public Sector study cohort study, which followed all employees working in one of 10 towns and six hospital districts between 1991 and 2005. The study included participants from a wide range of occupations including administrative staff, cleaners, cleaners and doctors, and they were followed up at four-year intervals regardless of whether they were still in the same jobs. Their survey responses were linked to a register of medication purchases for at least two years before retirement and two years after.

We had information on 2,766 participants who took retirement because of disability. Uniquely, the data included both participants’ use of medication and their perceived levels of work stress. So we were able to ask whether there were differences in this pre and post-retirement effect between those in low and high-stress jobs.

Specifically, we looked at something called effort-reward imbalance – that is, when workers put in too much effort at work but get few rewards in compensation: according to a recent review, this carries an increased risk of depressive illness.

If our theories were correct, we would see a decline in the use of psychotropic medication after disability retirement, and it would be greatest among those with high levels of effort-reward imbalance. Along with mental illness the other major cause of disability retirement in Finland is musculoskeletal disease, so we categorised our sample in three groups – mental illness, musculoskeletal disease and ‘other.’ Eight out of 10 in the sample were women, and three out of 10 reported high effort-reward imbalance before retirement.

Unsurprisingly, those who retired due to a mental disorder had the greatest increase in psychotropic drug use before retirement. And those who were in high-stress, low-reward jobs had higher levels of medication use than those who were not. But after retirement, there was no difference in psychotropic drug use between those with high vs low effort-reward imbalance. It looked as though stopping work in high stress jobs reduced the need for higher psychotropic medication use among those workers who exited the labour market for mental health reasons.

Retirement because of musculoskeletal disease or other causes was not associated with any similar link between stress level and psychotropic medication.

Lessons for employers

Our study showed that among people retiring due to mental disorders, those in high-stress, low-reward jobs benefited most from retirement. So it’s likely that they could benefit from the alleviation of work-related stress before retirement, too.

In conclusion, if employers could find ways of reducing the levels of stress suffered by employees suffering from mental ill-health, their early exit from paid employment might be prevented and their working lives might be extended.

Psychotropic medication before and after disability retirement by pre-retirement perceived work-related stress was published in the European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 0, No. 0, 1–6.

The other authors were Jaana Halonen, Taina Leinonen, Ville Aalto, Tuula Oksanen, Mika Kivimäki and Tea Lallukka of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; Hugo Westerlund and Marianna Virtanen of the Stress Research Institute, Stockholm University; Martin Hyde of the Centre for Innovative Ageing, Swansea University; Jaana Pentti, Sari Stenholm and Jussi Vahtera of the Department of Public Health, University of Turku; Minna Mänty of the Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki; Mikko Laaksonen of the Research Department, Finnish Center for Pension.

These authors also have the following additional affiliations: Jaana Halonen; Stress Research Institute, Stockholm University; Jaana Pentti; Department of Public Health, University of Turku; Minna Mänty; Statistics and Research, City of Vantaa, Finland; Mika Kivimäki, Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki and Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London; Marianna Virtanen, School of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu; Tea Lallukka, Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki.

This blog article is courtesy of the Work Life blog, which is a blog about the relationship between work and health and well-being of people, whether they are preparing for working life, managing their work / life balance or preparing for retirement and life beyond retirement. Led by the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies, University College London

By e.schaessens, on 5 December 2019

Author: Loren Kock, PhD student, Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group

Smoking cigarettes remains a leading cause of preventable death and disease in many high-income countries. Most of these harms fall disproportionately upon socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who generally have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent. In increasingly resource constrained health systems, what role does behavioural support that is tailored to an individual’s socioeconomic position (SEP) play in helping smokers quit and stay quit?

Smoking cigarettes remains a leading cause of preventable death and disease in many high-income countries. Most of these harms fall disproportionately upon socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who generally have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent. In increasingly resource constrained health systems, what role does behavioural support that is tailored to an individual’s socioeconomic position (SEP) play in helping smokers quit and stay quit?

Reducing health inequalities, which includes access and provision of health-care services, has been included as one of the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDG 10). Given that smoking is estimated to kill almost 8 million people a year and largely falls along a socioeconomic gradient, acting to prevent uptake of smoking and to help existing smokers quit is an essential part of this goal. Alongside other interventions and policies, the WHO’s ‘MPOWER’ package of measures to reduce the prevalence of smoking worldwide, provision of behavioural support to individuals trying to quit smoking is widely thought to be an effective approach. An advantage of these interventions is that health providers can be flexible in their delivery; support can be delivered in-person or over the phone, via digital media or through the use of financial incentives.

To tailor or not to tailor?

Even with the best support, most people relapse to smoking within the first month of quitting. Interventions that are tailored to smokers from disadvantaged groups stem from the knowledge that these individuals have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent than do those from more affluent groups. This is largely due to issues such as financial stress, absence of social support, addiction, lower confidence, stress, scarce life opportunities and less interest in the harms related to smoking. Because they don’t specifically address these barriers, it is generally thought non-tailored interventions are generally less effective among disadvantaged groups and may therefore be exacerbating existing inequalities. Compared with interventions that have no specific demographic target (non-tailored), interventions that are tailored to address these socioeconomic barriers (SEP-tailored) could, at least in theory, be more successful.

Our study published in the Lancet Public Health sought to tease out how much more effective, if at all, SEP-tailoring was for helping socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers quit.

Is SEP-tailoring more effective?

Our analysis of long-term (6 month) smoking cessation among disadvantaged participants from 42 randomised controlled trials revealed that individual-level behavioural support, regardless of whether or not it is tailored, can assist disadvantaged smokers with quitting. As aforementioned, tailored approaches specifically are expected to have an important role in reducing health inequalities by addressing some of the needs specific to disadvantaged smokers. However, further analysis revealed that when compared with not tailoring, SEP-tailoring was no more effective.

Quitting is hard

These results highlight the challenges that disadvantaged smokers face when making a quit attempt. It’s likely that behavioural support is effective in the short term, but the benefits wear off or disappear entirely when weighed against the circumstances and stresses that a recently quit ex-smoker faces every day. Dealing with the cravings and withdrawals associated with abruptly coming off the highly dependence-inducing nicotine from cigarettes, while also having to face unstable employment, low income, poorer housing conditions and general lack of support makes it much more likely that a disadvantaged ex-smoker will find themselves returning to smoking. It may be that even when tailored behavioural support attempts to adjust for SEP, it isn’t quite enough when weighed against these life circumstances. However, although no more effective than non-tailored approaches, tailoring is still an effective method; our analysis estimated that all types of behavioural support can improve quit rates by over 50%.

Doing more, and better

These findings don’t imply that tailored approaches should be abandoned. Instead, they should be a call to action for improved, multifaceted approaches at the individual, community, and population level that recognise the wider context of socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers. Sometimes complex problems require complex solutions!

Read the paper: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(19)30220-8/fulltext

By guest blogger, on 9 October 2019

Emma Walker, second year BBSRC-ESRC funded Centre for Doctoral Training in Biosocial Research PhD student at University College London’s Institute for Epidemiology and Health Care, describes how getting involved with research on social media helped her to reflect on her own usage.

Emma Walker, second year BBSRC-ESRC funded Centre for Doctoral Training in Biosocial Research PhD student at University College London’s Institute for Epidemiology and Health Care, describes how getting involved with research on social media helped her to reflect on her own usage.

It’s 00.23 and I should be in bed. I’ve got lots on tomorrow but I’ve spent the last 45 minutes scrolling. Scrolling through the profiles of Instagram “life style coaches”, yogis, models; each collection of photos perfectly curated to appeal to my desire for millennial aesthetic.

Everything feels so much better than anything I have. And actually, in the world of Instagram, I know that everything is much better than what I have. Number of followers or number of likes on each post has conveniently quantified this for me.

The next evening, as part of my public health PhD work, I’m reading Professor Yvonne Kelly’s paper laying out the effects of social media use on the mental health of girls. I diligently make notes “.. greater social media use related to online harassment, poor sleep, low self-esteem and poor body image .. ” “..girls affected more than boys..” and pause periodically to check my phone.

All my friends are at the pub having a great time, another friend just put up a post where she looks amazing, it already has 50 likes. I get to the methods section of the paper “how many times in the last 2 weeks have you felt miserable or unhappy; found it hard to think properly or concentrate; felt lonely; thought you could never be as good as other kids…”.

Then the penny drops. Why do I think I’m immune? I’m like the lifelong smoker who’s confused by their cancer diagnosis: “I never thought it would happen to me.” The idea starts to filter in: I don’t need this in my life. In fact, I need this to not be a part of my life.

The next day I deactivate my Instagram account. That day I meet a friend for coffee in a hipster café and don’t take a picture of my coffee. That night I get to sleep by 11pm. The next day I work more productively than I’ve worked in weeks.

An opportunity to get involved comes up: the National Literacy Trust are really interested in Yvonne’s work and are keen to put together an event for young people. A great group of undergraduates and I devise a series of activities to find out what young people think about the research.

The first section would involve 4 zones at the front of the Renaissance Learning centre room for Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree and Strongly Disagree we put a series of statements on the board and ask the pupils to move to a zone and explain why. We include statements on a range of topics including cyber bullying, sleep deprivation, self-esteem and body image and parents and social media.

On the day, the 50 enthusiastic 11-14 year olds from 3 schools across London jostle about, keen to share their opinions and to hear one another’s. I’m amazed at the diversity of ideas, overall willingness to get involved and the mental health literacy of many of the students.

Some responses are predictable; the boys happy to appear less concerned about body image, many keen to state in front of their teachers that social media does not in any way disrupt their studies. Some are surprising; only a handful of pupils had been on social media before arriving at the event that day (a significantly lower proportion than the adults running it!) Other responses are hard to read; were the gaggle of girls laughing at the very idea of social media posts making you feel left out, honest or desperate to seem not to care?

A clear feeling was the young people’s frustration at their parents use of phones and social media. Many expressed irritation at the rules their parents have established – no phones at the table, in bedrooms, after 8pm – that they, themselves constantly break.

One boy described having to ask the same question 3 times before his dad will look up from his phone. The idea that our event should be run for parents was cheered.

Next we presented them with the evidence base for the possible impact of social media and mental health then asked them to make public health campaign like posters with top tips that could go up in their schools. We were presented with a beautiful collection of posters with thoughtful advice, carefully put together information, clever slogans and eye catching drawings. Audio recordings from the day gave further insights from the young who readily offered tips and advice for younger children.

Overall, I think the event was a success. My main impression was that these young people are actually very well equipped to protect themselves from the potential mental health impact of social media. That in fact it may be people in their 20s, who have grown up in the full glare of social media and its pressures, who are at the greatest risk.

It was a real privilege being able to discuss this topic with young people and the message that stood out the most from them is the opportunity parents have to make a difference by practicing what they preach. Chances are they’ll benefit from switching off!

As for me, it’s now been 6 months since I deleted Instagram and whilst it hasn’t been plain sailing – I have got this itch for the buzz of an influx of likes – for the time being I’m happy and I would wholeheartedly recommend it!

By guest blogger, on 30 September 2019

We have a fantastic post below from Vennie an A-level student aspiring to study Medicine at university. She visited the Research Department of Primary Care and and shadowed some of our academics in their various projects in July. In this post talks about her experience and what she took away from it.

We have a fantastic post below from Vennie an A-level student aspiring to study Medicine at university. She visited the Research Department of Primary Care and and shadowed some of our academics in their various projects in July. In this post talks about her experience and what she took away from it.

Dementia is an increasing problem especially with the growing older population in the UK. The awareness of dementia is rising, especially through the use of media and organised events such as Memory Walks. However, how much do we know about dementia?

Well, in simple words, dementia is the ongoing decline in the brain. This is only an umbrella term for 200+ different sub-types of dementia that exists, some of which you may have heard off. For example the most common two are Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

During my placement in the Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health at the Royal Free Hospital, I was able to shadow members of the team that are involved at different levels of research projects.

I discovered that there are many stages which make up the process of a research project. Starting with the planning and design of the research project, ethics, and recruitment through to finally analysing and presenting the results produced. Alongside all this and integrated throughout are processes to ensure the results are implemented into clinical practice and policy, to make a difference. I learnt about the different types of studies such as qualitative studies and large clinical trials. Due to the involvement of human participants including often patients from the NHS in the studies the department runs, a major part of the research process is the ethical application and review. The purpose of the review is to establish if the project has more benefit than risk to the person and their family as well as is the project being conducted sensitively. For all of this to happen, it may take 5 to 20 years to see a difference in practice and policy.

In order for, this project to be successful, a range of people are required to take part, which in turns bring a variety of skills into the mix. These individuals may include designers, programmers, clinicians, psychologists, sociologists, statisticians, qualitative researchers, and importantly patients and their family themselves. A few of the most prominent skills are communication, teamwork, determination and resilience. For example, a project with Dr Davies and Prof Rait I observed on producing a support package for people with dementia and their families, communication has a massive role to play. The project uses workshops with people with dementia, their family and professionals to develop the support package. There is a need for clear communication between the ranges of people for this project to progress smoothly. The communication may come in the form of discussion-based in meetings, emails and many other ways. Therefore, teamwork is essential as each person will have a special role in the project. Finally, determination and resilience are required from every member of the team as there will be challenges along the way, which could be out of your control that must be overcome. For example, if the project does not meet the criteria of the ethics committee it may be returned to the researcher, and his or her team must go back and amend the plan.

In conclusion, research of any kind similar to this project requires a range of people to be involved with a variety of skills that are vital for the research to work. This work experience has been a fascinating and exciting opportunity for me to experience what goes on behind the scenes of a research project.

By guest blogger, on 5 September 2019

Authors: Aradhna Kaushal, John Isitt, Christian von Wagner, Douglas Lewins and Stephen Duffy

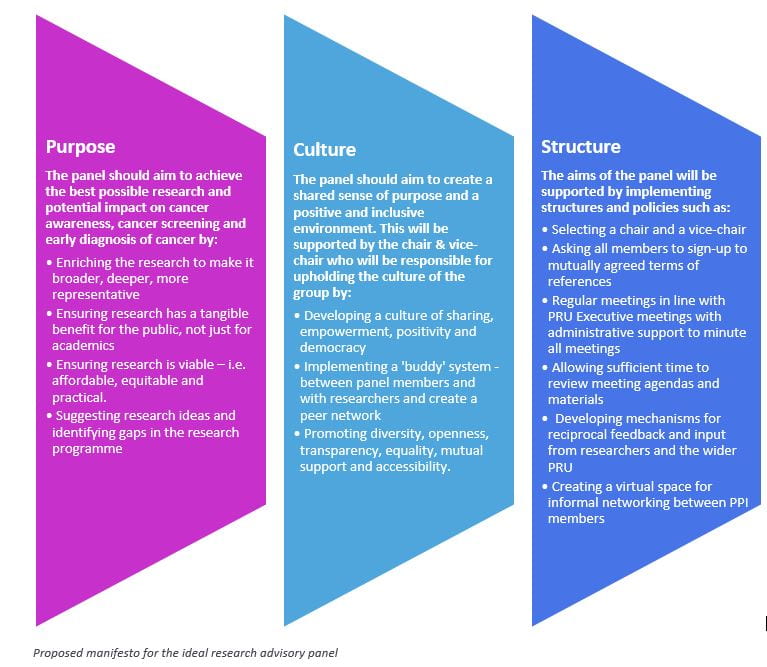

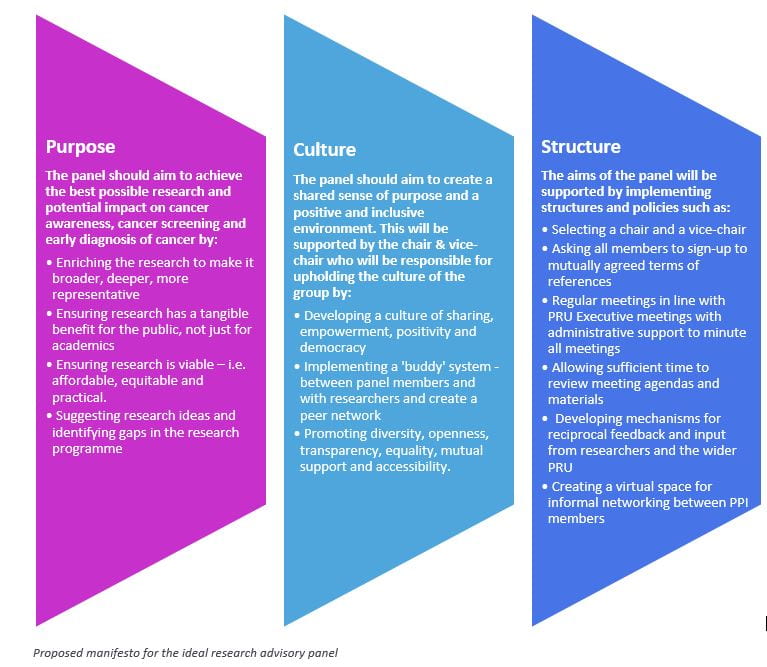

The Policy Research Unit (PRU) in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis recently set up a Research Advisory Panel to ensure that its research programme is relevant to and reflects the perspectives of patients and the public. In May, we ran a co-creation workshop designed to help the research advisory panel and PRU staff to build relationships with each other, to share ideas and experiences, to understand different perspectives, and to discover and prioritise discoveries together. The culmination of the workshop was the creation of a manifesto for the development of the Research Advisory Panel.

The Policy Research Unit (PRU) in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis recently set up a Research Advisory Panel to ensure that its research programme is relevant to and reflects the perspectives of patients and the public. In May, we ran a co-creation workshop designed to help the research advisory panel and PRU staff to build relationships with each other, to share ideas and experiences, to understand different perspectives, and to discover and prioritise discoveries together. The culmination of the workshop was the creation of a manifesto for the development of the Research Advisory Panel.

What did we do?

On the 31st of May we ran a co-creation workshop bringing together newly appointed patient and public members, with academics and administrators – to co-create the Research Advisory Panel’s (RAP) purpose, structure and culture to answer the challenge:

“What would the ideal Research Advisory Panel look like? What should it be responsible for? What’s the best way to involve PPI members effectively with academics and administrators? And how should it be organised?”

Co-creation in healthcare research, sometimes referred to as co-production, is “an approach in which researchers, practitioners and the public work together, sharing power and responsibility from the start to the end of the project, including the generation of knowledge” (NIHR, 2018). This approach is important in healthcare research as those affected by research are in an ideal position to contribute to the design and delivery of research through their unique experiences and knowledge.

The group was made up of nine patient and public involvement (PPI) members, four academic staff from the Policy Research Unit in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis (PRU), the administrator who supports the PRU, and the PRU’s director. Everyone participated equally in the workshop to co-create what an ideal Research Advisory Panel for the PRU would be like and how best to support and integrate PPI members.

What did we find?

In the first half of the workshop, recognising the differences in experience and diversity of the group, attention was given to create relationships, safety, permission and tools for sharing our personal experiences of PPI – the good, the bad and the ugly – and identified a range of attributes and obstacles to PPI in research. We discussed the importance of developing good relationships between PPI members, researchers and clinicians, and creating a positive environment for us to work together.

“As a new PPI member, you’re thrust into the midst of academics, physicians, etc and expected to make conversation over coffee. This can be a big obstacle for some people. They can be totally phased by the social demands.”

“Researchers tend to operate in cliques outside the meeting. [We] need to identify training for researchers to approach us as well as us approaching them.”

“If it really is about being a tick box, now I walk away. I’m not going to be complicit with that kind of game play. If I’m in the room, then accept me being in the room. You might not like everything that I say and that’s allowed, but please don’t have me here as a hologram.”

We then worked in small groups to create the future, writing manifestos for the ideal RAP in terms of purpose, culture and structure, which we presented back to the workshop. The main proposals are summarised below.

What happens next?

The insights from this workshop will be used to guide the future working relationships of the research advisory panel of the PRU. We are currently adopting the manifesto into our current terms of reference and way of working. We also have exciting plans ahead setting up a training and development plan for PPI members and virtual space where they can keep in touch with each other.

For anyone interested in running a similar workshop, please contact Partners in Creation.

By guest blogger, on 30 July 2019

With the help of a Researcher-Led Initiative award, PhD students Fran Harkness and Jo Blodgett, and Research Fellow Aradhna Kaushal organised a day of podcast training for early career researchers to learn how to beam their findings straight into the ears of the general public. Here they explain what a podcast is and how you can get started making your own.

Why podcast?

Why podcast?

Do you want to learn how to share your research discoveries beyond academic community (and pay-) walls? It would be unusual for a non-academic to read a journal, and as researchers, it’s not possible control how findings make headlines. But 6 million people in the UK listen to a podcast every week. And with people almost entirely listening to episodes as a lone activity- often on their phones whilst driving or travelling- the podcast has their full attention. Podcasts such as ‘All in the Mind’, ‘The Infinite Monkey Cage’, and our own Institute’s ‘The Lifecourse Podcast’ are easy to access (freely available online), and able to build a relationship with audiences through regular episodes. They disseminate new research in an informal style, often by chatting about new research with a fellow host, or interviewing academics.

Researcher-led initiative

We knew we wanted to make a podcast, but we didn’t know how. That’s where the Researcher-Led Initiative awards came in. We successfully applied for £1000 from the UCL Organisational Development to invite an experienced podcast trainer, Chris Garrington, and fellow academic and journalist Jen Allan to teach us everything we needed to make our own episodes.

Along with 13 other early career researchers, we learnt about the practical aspects of making a podcast such as how to conduct an interview, choosing recording equipment, incorporating jingles, editing audio files and disseminating podcasts online. We practiced recording and editing our recordings. It was such a buzz hearing our voices “introducing” our own podcast after the jingle. Of course 10, 000 more practice hours are needed before any Poddies are won but it was much easier than we thought it would be.

Recording a podcast series

We learnt that before you make your podcast, it’s important to consider the ideal format for the topic. For example, will a monologue or interview work best? Is the role of the presenter to ask questions on behalf of the audience or to offer their own opinions and thoughts? We also considered how many episodes are feasible to make, how often and how long should they be. Who are the audience and what kind of tone and style will appeal to them?

We experimented with sound quality between recording straight onto our laptops or enhancing it with different microphones, and received sage advice such as not to record in a coffee shop and to record some background sound separately when on you are on location in case you need to loop it in behind new recordings back in your studio (ahem bedroom). Jen then gave us a session of how to get the information you need from your interviewees, including to learn to soundlessly agree with them so to not cut them off (as qualitative researchers probably already know), and how to get around difficult questions.

What kit do you need?

You don’t need highly specialised equipment to make a podcast. An investment in a good microphone will ensure the quality of the audio recording. You may also consider different types of microphones (such as lapel microphones or hand-held) for different needs. You can also record interviews via Skype or Zoom using an Ecamm Call Recorder. Once you have your audio file, you can edit this using freely available software such as GarageBand (Mac) or Audacity (Windows). When you are ready to share your podcast with the world, you can share this using a podcast hosting website such as Libsyn: A podcast host simplifies and automates both the RSS feed and file hosting and delivery to your subscribers. But a good host does more than that by providing useful stats, tutorials, and support.

Thanks to Chris and Jen, we somehow finished the day with a mini episode and many big plans for the future! Watch this space.

By guest blogger, on 11 July 2019

The teenage years are a time for experimenting and for pushing boundaries – particularly when it comes to intimate relationships. Such experimentation is a natural part of growing up. But there are potential risks, too – particularly if these early experiences aren’t positive ones. A new study from Professor Yvonne Kelly from UCL’s Department of Epidemiology and Public Health and colleagues, investigates what kinds of intimate behaviour 14 year-olds engage in, and asks how this insight can help to ensure young people are well prepared for healthy and happy adult relationships.

We know teenagers experiment with intimacy, often moving ‘up’ the scale from hand-holding or kissing to more explicitly sexual activity. But we also know teenage pregnancy numbers have been dropping in recent years. And our new study suggests that fewer young teenagers are actually having sexual intercourse than some might previously have thought.

We’ve all seen the headlines – studies have shown us (links) that 30 per cent of those born in the 1980s and 1990s had sex before the age of 16, and that among those born in the early 1990s a little under one in five had done so by age 15. But our new evidence, based on 14 year-olds born during or just after the year 2000, paints a rather different picture of this latest generation of teenagers.

Our research used data from the Millennium Cohort Study, the most comprehensive survey of adolescent health and development in the UK. It follows children born between September 2000 and January 2002 and has collected information on them at nine months and subsequently at age three, five, seven, 11, and 14 years. We used information from the most recently available data, when the study’s participants were 14 years old, and were able to look closely at the lives of 11,000 of them.

Intimate activities

Participants were asked about a range of ‘light’, ‘moderate’ and ‘heavy’ intimate activities. Handholding, kissing and cuddling were classed as ‘light,’ touching and fondling under clothes as ‘moderate’ and oral sex or sexual intercourse as ‘heavy.’

As might have been expected, more than half – 58 per cent – had engaged in kissing, cuddling or hand-holding, while 7.5 per cent, or one in 13, had experienced touching or fondling. But in contrast to other studies, (though our sample was younger than those mentioned above) we found only a very small proportion – 3.2 per cent or fewer than one in 30 – had been involved in ‘heavy’ activities in the year before they were interviewed for the study.

And most parents can take comfort from the fact that if their children aren’t participating in other risky activities such as drinking or smoking, they probably aren’t having sex either – there was clear evidence of links between heavier sexual activity and these factors.

We also found those who were most likely to confide worries in a friend rather than a parent, those whose parents didn’t always know where they were and those who stayed out late were more likely than others were to be engaged in heavier forms of sexual activity. Other potential links were found to drug-taking and as well as to symptoms of depression.

Our findings suggest young people who push boundaries may push several at once – that those who drink, smoke or stay out late, for instance, are more likely to engage in early sexual activity.

So, initiatives which aim to minimise risk and promote wellbeing are crucial – and they need to look at intimate activities, health behaviours and social relationships in relation to one another.

A key point is that if young people can learn about intimacy in a positive way at an early stage, then those good experiences can build foundations which will help them throughout their lives.

Most importantly young people need to know how to ensure their intimate experiences are mutually wanted, protected, and pleasurable. The concept of “sexual competence” – used to refer to sexual experiences characterised by autonomy, an equal willingness of partners, being ‘ready’ and (when relevant) protected by contraceptives – is important at all ages, as are close and open relationships with parents.

Better understanding of this interplay between personal relationships and behaviours are key to better support for young people. The right intervention at the right time can ensure a teenager’s intimate life is set on a positive course.

Partnered intimate activities in early adolescence – findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study, by Yvonne Kelly. Afshin Zilanawala , Clare Tanton, Ruth Lewis and Catherine H Mercer,is published in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

*Afshin Zilanawala is based at the Research Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, and Oregon State University, United States.

Clare Tanton is based at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Ruth Lewis is based at the University of Glasgow.

Catherine H Merceris based at University College London.

This blog article is courtesy of the Child of our Time blog, which is a blog about the health and happiness of children living in the UK. led by the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies, University College London,

By guest blogger, on 12 June 2019

Picture Credit: Ibrar Dar

Authors: Chantal Edge, Dr Binta Sultan, Serena Luchenski, Dr Al Story

There’s no avoiding the fact that health is getting worse for people who are at the extreme edges of society. The number of people sleeping rough has almost doubled nationally. Deaths among homeless people and people who use drugs are increasing, and we are putting more people in prison. This is driven by social and political forces. Over the last decade, austerity has led to record numbers of working families living in poverty and major increases in child poverty. Housing is unaffordable to millions, foodbanks have proliferated, children’s and youth centres have seen systematic disinvestment, and access to legal aid has been greatly reduced. At the same time, funding is decreasing for services which reduce the harms of extreme social exclusion, such as addiction treatment, needle exchange and hostels.

So what should we, as a multidisciplinary research and advocacy group, be doing to stem the tide of inequity? How can we stop people from becoming socially excluded, improve services for people who are, and ultimately help people escape exclusion? The team at our newly launched UCL Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health has reached out to experts with lived experience of exclusion, policy makers, voluntary sector, health and social care workers and academics to frame our research and advocacy priorities for the next five years.

So what is Inclusion Health?

“Inclusion Health is a service, research, and policy agenda that aims to prevent and redress health and social inequities among the most vulnerable and excluded populations.” (Luchenski 2017, The Lancet)

Put simply, Inclusion Health is about understanding the forces that cause and perpetuate social exclusion so we can prevent it and bring vulnerable and under-served people in our society ‘out of the cold’. People who are homeless, drug users, prisoners, or sex workers suffer from poorer health outcomes than people in the general population and are far more likely to die early. Research at UCL found that women from these socially excluded groups were 12 times more likely to die than other women of the same age, and men eight times more likely. People who are socially excluded are more likely to be murdered or commit suicide and more likely to die from accidents, overdoses, infectious diseases, cancers, liver disease, heart problems and respiratory diseases. Social exclusion damages health, destroys lives and fractures communities. Dedicated research and advocacy to highlight the harms of exclusion and remedy the causes is urgently needed.

What is the new UCL Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health?

The UCL Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health (CCIH) was set up by a multidisciplinary team of researchers, experts with lived experience and frontline professionals who are dedicated to reducing health inequity. The Centre already has a broad range of research projects underway, measuring the health harms of exclusion and developing and testing interventions to improve the health of excluded groups. At the heart of all these projects are partnerships with people who have lived experience of exclusion (‘experts by experience’) and professionals from across the public and voluntary sector.

Co-producing the Inclusion Health agenda

Picture Credit: Ibrar Dar

On 3rd June 2019, the Centre held a launch event to bring together a wide range of experts to shape the agenda and co-produce research and advocacy priorities for the next five years. Over 100 representatives from the voluntary sector, policy, academia, healthcare and a wide range of experts by experience worked together to tackle three key areas – preventing exclusion, improving services for those who are excluded and escaping exclusion. Through a series of presentations, workshops, democratic voting and ‘dream-boarding’ we collected and collated information on where we need to start.

Consultation and analysis is on-going but emerging priorities include:

- Tackling the upstream determinants of exclusion – political determinants, poverty and traumatic childhoods

- Addressing societal and professional ignorance, indifference and stigma that can further deepen and perpetuate exclusion

- Making services more accessible and integrated to stop people falling through the cracks

- Ensuring that experts by experience are at the heart of health research, service development and decision making

- Creating better routes out for people to escape exclusion

This event was run in partnership with the UCL Centre for Co-Production in Health Research and made possible by funding from UCL Grand Challenges.

Next steps

Over the coming months we’ll be disseminating our findings from the day. We will use this evidence to inform and influence research and advocacy priorities for funders, and ensure that our current and future research projects tackle the priorities that have been set.

There is a legal duty in England on politicians and policy makers to better integrate services and tackle health inequalities. People forced to the margins of our society suffer from humiliating disadvantage, preventable disease and premature death. Their lives, cut short, indicate that there is something toxic in our society. Evidence to inform better policy, practice and advocacy is urgently needed.

Picture Credit: Ibrar Dar

Chantal Edge is an NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellow and Specialty Registrar in Public Health, researching the use of telemedicine for hospital appointments in prison. Dr Binta Sultan is an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow and a Consultant in HIV and Sexual Health, her research centres on improving hepatitis C linkage to care in people who experience homelessness using novel technologies. Serena Luchenski is an NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellow, a Consultant in Public Health and Chair of the UCL Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health; her research is on developing a public health preventative approach to hospital care for people experiencing homelessness. Dr Al Story leads the Find&Treat Outreach Service based at UCLH and is Co-Director of the UCL Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health.

Picture-credit-Binta-Sultan

If you’re interested in learning more about Inclusion Health we run a short course on Homeless and Inclusion Health at UCL. This can also be taken as an optional MSc module on the MSc Population Health or any UCL MSc programme. It has no pre-requisites and we welcome interested participants from any sector. You can find more information here.

If you are interested in becoming involved in Inclusion Health research please contact us at ccihcore@live.ucl.ac.uk outlining your area of interest.

By guest blogger, on 17 May 2019

In this post Ruth Abrams and Sophie Park reflect on the current pressures facing GPs and NHS today.

In a recent expose called ‘GPs: Why Can’t I Get an Appointment?’, a Panorama documentary, which aired on BBC1 on Wednesday 8th May, emphasised the current limits of and pressures on the NHS system. The programme featured interviews with overworked GPs and allied healthcare professionals, painting a rather bleak picture. Practices are merging and closing at an ever increasing rate. Patient loads increase as patient lists are subsumed. Patient multi-morbidities have increased the need for chronic conditions to be monitored with regular GP appointments. Yet on average patients wait a minimum of two weeks for a routine appointment. Early retirement and a limited flow of trainees into General Practice also contribute to the strain, making practice sustainability difficult to envisage. Inevitably, pressure and frustration are being felt amongst both patient groups and the primary care workforce.

In a recent expose called ‘GPs: Why Can’t I Get an Appointment?’, a Panorama documentary, which aired on BBC1 on Wednesday 8th May, emphasised the current limits of and pressures on the NHS system. The programme featured interviews with overworked GPs and allied healthcare professionals, painting a rather bleak picture. Practices are merging and closing at an ever increasing rate. Patient loads increase as patient lists are subsumed. Patient multi-morbidities have increased the need for chronic conditions to be monitored with regular GP appointments. Yet on average patients wait a minimum of two weeks for a routine appointment. Early retirement and a limited flow of trainees into General Practice also contribute to the strain, making practice sustainability difficult to envisage. Inevitably, pressure and frustration are being felt amongst both patient groups and the primary care workforce.

Whilst those researching, working in and experiencing primary care within the UK will already be familiar with these factors, what has become a pressing concern since the 2015 publication of the BMA’s, National survey of GPs: The future of General Practice, is patient safety. At present only the most urgent of cases are seen quickly in General Practice. Yet still an unsafe number of patients are seen by any one GP in a day. This high demand placed upon GPs makes for little time to reflect on cases.

Enter- the release of the new GP contract and the NHS long term plan which intend to employ a multi-disciplinary army of healthcare professionals. Within this new way of working, workloads will be shared amongst staff, with greater efforts being made for both integration and collaboration. A typical GP’s day will begin to look very different. Micro-teams will have time to discuss patient cases, a GP’s time can once again be focused on the professional tasks only they can undertake and overall there begins to be a healthier outlook to teamwork.

Some promote this utopian vision of General Practice working unquestioningly. Pots of money, such as those made available through the Prime Minister’s Fund, have encouraged new ways of working with very limited evidence base. Yet one aspect seemingly unaddressed within the new plans is the disparity across patient access and levels of deprivation within the UK. In a recent report by the Health Foundation, GPs working in higher deprived areas see more patients compared to their counterparts. These are areas where recruitment of this new workforce will inevitably be harder. This raises questions about how best to incentivise recruitment so that patient access to care remains equal for all.

There is also a certain feel that these plans are being done to, rather than with GPs. We need only reflect back a few short years to the junior doctor protests to recall that in order for patient safety to happen, workforce perspectives must be accounted for. In order for the NHS to remain as successful as it has been and for the principles of Astana declaration to be realised, GP engagement rather than negation needs to remain central to all future planning activities.

Unequal access to care and a disruption to professional identities present major issues. But doing nothing is no longer an option. At a time when the NHS is so often synonymous with the words crisis and strain rather than success, a Utopian vision for both staff and patients may be both timely and necessary. Reifying this however, becomes a different matter all together.

By guest blogger, on 16 May 2019

Is retirement good for your heart, or bad for it? The question is an important one because cardio-vascular disease (CVD) is the biggest cause of death globally and costs health services a huge amount of money.

Some studies have shown retired people have a higher risk of being diagnosed with CVD than those who are still working. But until now the evidence has been unclear.

We set out to review evidence from across the world, so that we could help to build a more accurate picture of whether, and how, retirement might affect our cardio-vascular health. As CVD is linked to our lifestyle, diet and other behaviour, there are lots of ways in which changes that take place in retirement might have an effect – both negative or positive.

Longitudinal studies

We looked for longitudinal studies that could help answer our questions, and found 82 which measured risk factors for CVD and 14 which looked at actual incidence of CVD. The second set of 14 papers provided the answer to our first question – does retirement affect our cardio-vascular health?

The answer revealed a major difference between the USA and Europe. Studies conducted in the US showed no significant effect, good or bad, on retirees’ cardio-vascular health. In Europe, meanwhile – with the exception of France – studies consistently showed a link between retirement and an increase in CVD.

Data from the British Regional Heart Study, for instance, showed that healthy men who retired before the age of 60 were more likely than others to die from circulatory disease within five and a half years. Fatal and non-fatal CVD was also more common among retirees in Denmark, Greece, Italy and the Netherlands.

Why might this be? Could there be cultural or lifestyle differences between Europe and the US which might cause this difference? We took a systematic look at the risk factors.

Weight gain

First, we looked at weight gain. If Americans were less likely to put on weight after retirement compared to Europeans, that might help to explain the difference. But when we looked at this, we found that body mass index (BMI) actually increased after retirement in the USA – and also Japan -but did not change in England, Denmark, France, Germany, Switzerland or Korea. While those who do physically demanding jobs are likely to put on weight after they retire, most people aren’t.

Could it be that retired people generally do less exercise – another risk factor – in Europe? The studies suggest that’s not the reason. While many retirees did more physical activities, they also spent more time sitting still – so the effect was a balanced one. For instance, a retiree might play more golf, but also watch more television.

Do retired people perhaps smoke more, we asked? Again, there were contradictory results but 12 out of 14 studies either showed no effect or showed retirement led to people smoking less.

Perhaps retired people in Europe drink more, then? Again, this couldn’t be identified as the reason. Studies in Australia, the UK, Japan and the USA suggested there was no association between retirement and alcohol consumption.

Diet is another possible cause of CVD, but again, there was no clear pattern of between retirement and diet emerged from reviewed studies.

No benefits

So the picture isn’t straightforward, and we don’t have answers as to why retirement might put Europeans at risk but not Americans. What we can say, though, is that none of the studies we looked at found any beneficial effects of retirement on CVD.

Apart from a decrease in smoking, there wasn’t evidence of any general ‘relief’ effect of retirement on people’s cardio-vascular health – so the supposition that working could be bad for our health and therefore retirement better for it doesn’t necessarily hold true.

However, studies that showed retirement brought negative health effects should be interpreted with caution. Many assessed the health effects of retirement by comparing retired people with employed people – and we know people who stay in the labour market are generally healthier than retirees. We do know people who have CVD, diabetes or hypertension are more likely to retire.

What our review has done is to reveal the complex nature of the underlying mechanism through which retirement might impact on the risk factors for CVD. Different people react differently to retirement, depending on their life experiences and the cultural and policy environments in which they live. So there isn’t one global solution to any of this – each country needs to plan its citizens’ retirement according to their individual needs.

The impact of retirement on cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: A systematic review of longitudinal studies, by Baowen Xue, Jenny Head and Anne McMunn, is published by The Gerontologist.

This blog article is courtesy of the Work Life blog, which is a blog about the relationship between work and health and well-being of people, whether they are preparing for working life, managing their work / life balance or preparing for retirement and life beyond retirement. Led by the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies, University College London,

Close

Close