What’s law got to do with it?: Reflecting on my time in the Q-DaPS team as an In2research student

By Eleanor Mason, on 17 July 2025

Student Shania Essah Aurelio shares her experience with the Q-DaPS (Qualitative Data Preservation and Sharing) team at the UCL Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care through In2research. In2research is a one-year programme developed by In2scienceUK and UCL, designed to enhance access to postgraduate research degrees and career opportunities for people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and under-represented groups.

Why I chose this placement

The Q-DaPS study is a multidisciplinary research study led by academics and Public & Patient Involvement (PPI) experts. It is funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research (FR4 – Project No. 596).

The study’s primary objective is to create a centralised repository for qualitative health and social care data that is secure and trustworthy. To inform the repository’s design and infrastructure, this study involved interviews with data professionals and qualitative researchers as well as focus group discussions with PPI collaborators who have previous experience of participating in primary care research.

Despite not coming from a medical sociology background, I applied to the Q-DaPS project for three main reasons:

- I was curious to look at health data from a different perspective. For context, I was completing my Masters degree in Law at the time, where I had been researching data protection laws and how they’re applied to personal data processing activities in the public sector.

- I wanted to learn about how qualitative data are used and managed in health and social care research, as well as the issues that may arise from this.

- It was clear that collaboration was at the project’s core from the very beginning and I wished to be part of a co-created project between academics and PPI contributors.

Looking back, I can confidently say that my time with the Q-DaPS team has definitely exceeded those expectations.

Working with the research team

Throughout my placement, I met and worked with various members of the Q-DaPS team: Professor Fiona Stevenson (who was my placement host), Professor Geraldine Leydon, Dr Barbara Caddick, Dr Karen Lloyd, and patient and public involvement (PPI) experts Lynn Laidlaw and Ali Percy.

PPI increasingly plays a central part of health and social care research. Safe to say, I had never worked with PPI contributors before. That, mixed with the readings I’ve done in a discipline I’d never come across before, would explain why I came to the first full team meeting with a page full of questions: from “how does triangulation work?” to “how do PPI contributors get onboarded on research projects like this?”. I knew that delving into a whole new discipline was going to be a challenge, so I’m thankful to the Q-DaPS team for actively involving me in their discussions and patiently explaining concepts and terminology that I couldn’t get my head around.

Another in2research student, Kim McBride, also joined the Q-DaPS team later that summer. Even though we didn’t start our placements at the same time, we got to work together on days when our schedules overlapped. In retrospect, it was probably for the best—every time we were in the same room together we always ended up chatting about our studies and research interests. I really enjoyed working with Kim; like the rest of the Q-DaPS team, her contributions were informed by the work she’s done in her discipline (which is Social Psychology) and getting to see the same dataset (i.e., focus group transcripts) from her perspective was incredibly valuable.

Working on my project

The Q-DaPS project involved a qualitative multistakeholder study, which essentially means that there’s a lot of reading involved—especially in the earlier weeks of my placement. Before homing in on the focus group transcripts, I went through interview transcripts from the multistakeholder study, where I gained insights from various experts in the field (i.e., PPI contributors in health and social care research, researchers, and data protection lawyers).

Having gone through the focus group and interview transcripts, I ended up researching the intersections between UK data protection law and health data-related research ethics. I mainly focused on the UK GDPR as well as the Taipei and Helsinki Declarations. Through this placement, I got to explore the connections between them which I thoroughly enjoyed.

What made the research process enriching was the feedback phase; this is where the varied expertise of the Q-DaPS team shined. Looking back on the dialogue I developed with the Q-DaPS researchers through the ribbons of comments on my research outline, I have learned so much from their experiences—from how data protection laws are applied in academic settings to how data ethics are approached by ethics committees across institutions.

Even though I was based in the Department of Primary Care and Population Health, I got to meet researchers from other departments. From them, I learned more about topics like social prescribing, safety standards for baby food, and even health economics—things I’d never looked into before. Being able to hear about their research and share experiences and anecdotes with them really encouraged me to keep going with my project.

The chances of being onboarded onto a medical sociology research project with a CV filled with legal research experience are very slim, and I am very grateful to the in2research team for having afforded me this opportunity by matching me to the Q-DaPS placement. My gratitude is extended to the Q-DaPS team, who have warmly welcomed me into their side of the research world and enthusiastically encouraged my curiosity.

Unlock your creative potential: Embrace innovative research outputs using our new online learning package

By Eleanor Mason, on 9 September 2024

As UCL researchers we strive to create dynamic and inclusive research environments. This means using more creative and innovative ways of sharing and demonstrating research excellence, in addition to traditional outputs like published research papers.

An “Improving Research Culture” small grant was awarded to Aradhna Kaushal (Institute of Epidemiology and Healthcare) and Shoba Poduval (Institute of Health Informatics) to share their experience of developing creative research outputs and produce a learning package for UCL early career researchers with examples and guidance.

Aradhna and Shoba identified a number of Research Culture priorities from key reports including UCL’s 10-year Research Culture Roadmap. This includes ‘Openness and integrity in our research and innovation’ and identifies supporting and rewarding non-traditional outputs alongside more traditional ones as a research culture priority at UCL.

They have developed an online interactive learning package with several examples of creative outputs from UCL researchers including podcasts, animations and events, and a step-by-step ‘how to’ guide.

An example of the creative outputs showcased in the learning package is the video abstract below.

The learning package aims to:

- Explain the range of diverse research outputs with traditional and non-traditional examples.

- Explain why diverse research outputs are important for the UCL, individual researchers, and for communities.

- Understand the steps needed to create diverse research outputs, including collaborating with artists and creatives.

Creative research outputs help to communicate your findings more effectively, engage a broader audience, and make a lasting impression. Exploring creative methods enriches your skill set and opens doors to new collaborations. The learning package offers flexible learning at your own pace, with expert insights, examples and tips collated from multiple projects and provides a forum for sharing ideas and connecting with others.

Embracing creative research outputs can elevate your work, making it more engaging and influential.

Ready to get started?

Explore today by completing the diverse research outputs learning package. You just need to enter your email address and a password – this is so that you can return to the course and receive a certificate of completion.

Acknowledgements:

This project was funded by a UCL Population Health Sciences ‘Improving Research Culture’ small grant. With thanks to Sarah Barnes, Maria Kett, Nicola Phillips, Sarah Assad and Megan Armstrong for peer review, and everyone who contributed examples of their work.

Social Capital and Political Dynamics in the Refugee Experience

By Eleanor Mason, on 19 August 2024

This blog for World Humanitarian Day (WHD) by visiting PhD student Samah Halwany from UNIMC-Italia explores the implications of refugees’ precarious status on their dignity, identity and overall well-being. Samah’s thesis investigates the strategies that Syrian refugee women with disabilities utilise to foster their social inclusion in Gaziantep, Türkiye.

The 2024 WHD theme, #ActForHumanity, focuses on addressing the alarming rise in attacks against humanitarian workers and civilians, advocating for the enforcement of International Humanitarian Law to end impunity for these violations.

Refugees often navigate a challenging landscape of displacement and uncertainty, which significantly hampers their efforts to rebuild their lives. In this blog I will explore how the broader socio-political challenges encountered by refugees are often exacerbated by political labelling.

The humanitarian principle is founded on the protection of all individuals. However, individuals in vulnerable situations are often subjected to political categorization, which significantly shapes how their presence in the world is perceived. According to Samuel Dinger (2022), the concept of rights is closely linked to one’s status as a citizen of a sovereign nation. if a country were to lose its sovereignty, individuals may also lose certain rights. This leads to their categorisation based on political status, such as “migrants”, “refugees” “displaced persons” (as used in Lebanon), and those “under permanent protection” (in Türkiye). The semantic distinction is significant and has been the subject of considerable scholarly and political discourse. Notably, state authorities frequently employ the term “migrant”, “displaced”, “permenantly protected” to implicitly challenge the legitimacy of individuals seeking asylum, while non-governmental organisations conversely utilise “refugee” to underscore the veracity of their protection claims (Fassin 2021, p. 63).

The rights of refugees are primarily restricted to the provision of services, which are often short-lived, dependent upon the availability of international aid. The availability and nature of these services can vary significantly based on the location where refugees are placed in relation ot the hosting population (Dinger 2022). Basic services are usually the only rights available in camps, whereas outside the camps, individuals may have access to formal education, livelihood opportunities, and social engagement. However, in both settings, political attitudes often aim to keep individuals in a state of temporary emergency with the goal of returning them to their home countries, whether by choice or by force.

Governments often view refugees as mere numbers to manage, restricting their mobility and quality of life to encourage return and prevent permanent resettlement. They may also resort to using refugees to secure international funding and may threaten repatriation if aid is reduced, while fostering negative sentiments to gain electoral support (the case of Lebanon and Türkiye). In contrast, humanitarian agencies focus on emergency contexts, struggling to overcome barriers to increase their services. This dichotomy frequently reduces refugees to statistics and emergency cases, overshadowing their broader human dignity and rights.

In this context, refugees face daily challenges that undermine their human dignity and the value of their lives. They lose all privileges and social and cultural capitals once labelled politically. Those with economic capital are often more readily accepted and integrated into host communities. For many refugees, especially those living outside controlled zones such as camps, survival depends on building social capital within both the host and their own communities to access economic resources and gain solidarity. Through these interactions, refugees may find jobs and establish NGOs to support their communities. However, host governments generally accept this social capital only if it does not challenge the status quo. In Lebanon, for example, refugee activists who collaborated with Lebanese counterparts to advocate for the rights of refugees and other vulnerable groups began to gain social position. Unfortunately, activists became targets for attacks, facing threats from local authorities and armed individuals, and were subjected to detention. Security forces investigated their mobile contacts, questioned them about their associations with activists, and used various tactics to make them feel unsafe, including surveillance and, in some cases, torture (as recently documented by the Access Centre for Human Rights (ACHR, July 2024). Some activists were even threatened with deportation back to Syria. To escape these dangers, many sought asylums at European embassies, hoping for a better life while leaving their families behind under threat until they could reunite.

Even though refugees often lose the social and economic resources they acquired in their homeland to survive in host countries, they strive to resist the political attitudes that reduce their existence to its most basic form. They work to maintain their dignity and identity despite being perceived as a “burden” or “confined” to camps, as described by Shaabo (2024). This struggle reflects a broader issue of “double absence”, a concept introduced by Algerian sociologist Abdelmalek Sayad as cited in Yafa’ al Hasan (2024). It is the feeling of being “neither here nor there,” meaning they are neither truly present in their country of origin nor fully accepted in the host country. This ongoing struggle underscores the complex challenges refugees face as they seek to assert their identity and rights in a world that often oppresses them.

A human-rights centred approach is essential to address the complex challenges faced by refugees. This requires robust advocacy, rigorous monitoring of human rights violations, and empowering refugee-led initiatives. International collaboration among organizations, governments, and refugees is crucial for developing sustainable solutions, reforming laws to protect and include refugees, and validating their experiences. By prioritizing refugees’ lives and rights, we can advance an “ethics of life” that encompasses not only physical safety but also the “living beings and the lived experiences”-“le vivant et le vécu”(Fassin p 42).

Furthermore, socio-economic integration programs and joint community development initiatives can bridge the gap between refugees and host communities, as well as promote cooperation in economic and community development projects. Cross-cultural exchange programs and heritage sharing can further strengthen this connection, allowing refugees to preserve their culture while adapting to their new environment.

By prioritising these recommendations, we can create a future where refugees are seen not as ‘problems’ needing basic survival support, but as active participants valued for their full humanity.

References:

- Fassin, D. (2018) La vie. Mode d’emploi critique, Condé-sur-Noireau, Seuil.

- Dinger, S. (2022). Coordinating Care and Coercion: Styles of Sovereignty and the Politics of Humanitarian Aid in Lebanon. Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 13(2), 218-239. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hum.2022.0009.

- Shaabo, R. (2024, March 12). حين تصبح الهوية عبئاً (المثال السوري)) [When Identity Becomes a Burden (The Syrian Example)] Raseef22. https://raseef22.net/article/1096763 .

- Al Hasan, H. (2024, June 9): من أنت، إلى أين تنتمي؟”… أسئلة الهوية الملحة عند المهاجرين [Who are you, and where do you belong?” … Urgent Identity Questions for Migrants] Raseef22. https://raseef22.net/article/1097521

- Access Centre for Human Rights-ACHR, Private Letter (July 11,2024): Lebanese Authorities must Immediately Stop Intimidating Human Rights Activist. As a joint statement by Human rights organizations-not published. Website: https://www.achrights.org/en/

Fried egg sandwiches and a recipe for digital inclusion

By Eleanor Mason, on 12 June 2024

The team behind the Digital Health Inclusion Project check in with the Breakfast and Browsing group at Burmantofts Community Friends. This blog was written by Lily Arnold and Emma Carta (UCL Research Assistants).

Introduction

The Digital Health Inclusion Project at UCL has been researching Digital Health Hubs across Leeds for the last year. These hubs are part of a community based approach to digital inclusion, facilitated by 100% Digital Leeds, in collaboration with VCSOs and the health sector.

As the project wraps up, we took a last visit to the Breakfast and Browsing club run by Burmantofts Community Friends, to check in with the group members about our initial findings. Some members have given their time to the project already, but this workshop allowed us to open up discussions with the group and hear more experiences and perspectives.

Digital exclusion has wide-ranging implications for individuals, including poorer health outcomes, increased social isolation, and limited access to essential services. The National Government has been criticised for lacking a credible strategy and failing to prioritise the issue of digital exclusion effectively. But local authority led interventions in Leeds, which are delivered through community hubs and partnerships, play a crucial role in reaching digitally excluded individuals and building essential skills and confidence.

Workshop Overview

We began the session thinking about what works well at the Breakfast and Browsing group, asking the members why they enjoy coming along to the sessions. Then, armed with craft supplies, we turned these discussions into recipe books coming up with recipes for getting online.

While participants mostly only finished the covers of their recipe books, the conversations happening around the table were very insightful! As the workshop drew to a close, instead of a recipe book, members of the group asked for their work to be turned into a poster which could advertise the Breakfast and Browsing sessions to a wider audience.

Key Findings from Field Notes

- Participants enjoyed and appreciated the warm and welcoming atmosphere of the group, and talked often about the importance of social connections and friendship. Multiple times, and in different contexts, the word ‘family’ was used to describe the bond the group felt to each other.

- Breakfast and Browsing meets the need for personalised and flexible approaches to digital inclusion, and it recognises the diverse needs and preferences of individuals who attend the session.

- In depth, ad hoc, one on one digital inclusion work takes place at the periphery of the sessions, with light touch scaffolding at the centre for those who want to engage.

- The breakfast element of Breakfast and Browsing is so much more than just a meal, eating together contributes to the warm atmosphere of the group and establishes a trusted routine.

- The time the group runs on a Monday morning was also noted as being useful, with participants describing their participation as starting the week off on the right foot.

Checking in with the Breakfast and Browsing group provided valuable perspectives from participants on what makes Digital Health Hubs successful. Just as the group requested, here is a poster which combines their different ideas together to advertise the session for more people to join:

Hosting a dementia workshop for health care professionals and caregivers – a reflection

By Eleanor Mason, on 6 December 2023

Alice Burnand, Associate Researcher, Centre for Ageing Population Studies (CAPS) shares her experience hosting a dementia workshop.

Introduction

On October 11th, 2023 I hosted a workshop to share results from our research project, which brought together a variety of individuals such as clinicians, caregivers, and researchers. Our research project involved evaluating the current literature on the non-pharmacological interventions to manage psychosis symptoms in dementia, such as hallucinations and delusions. I wanted to share the take-home messages of this research, to improve the quality of care that is delivered to people living with dementia. The workshop, however, was not just about sharing knowledge but also about rich interactions, meeting individuals who have unfortunately been affected by dementia-related psychosis, the exchange of ideas, and invaluable feedback about this important research topic.

The Workshop’s Concept

The workshop was titled “non-pharmacological interventions in the management of dementia-related psychosis”. It aimed to educate the audience on the symptoms and causes of psychosis in dementia, how to optimise physical health and the environment for someone, and to share the current literature to best support individuals without the need for medication. It also aimed to inform the audience of the risk of bias in research, to enable them to make informed decisions about the quality of the papers that we discussed. The aim was to empower caregivers and healthcare professionals, and to share valuable tools that can be used to support people living with dementia.

Planning and Preparation

It all began with meticulous planning and inviting a guest speaker to collaborate and join. In the months leading up to the event, I outlined my goals, determined my target audience, and designed the content to be engaging and informative. I originally wanted the workshop to be help in person, with 20 attendees, however, I quickly gained a vast amount of interest following circulation of the information, with nearly 100 people signing up asking to join. I chose to do the workshop hybrid, to make it as accessible as possible and so that everyone who wanted to join, could. For those coming in person, I chose a venue in a central London location, and ensured I provided all the necessary supplies, including printouts, drinks, and importantly, chocolate biscuits.

The Workshop Experience

Learning and content

The workshop started with educating the audience on psychosis in dementia and how to prevent it by ensuring physical health is optimised. It was led by myself and the guest speaker, Dr Stephen Orleans-Foli, who is a consultant psychiatrist working in the Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Service, West London NHS Trust. We then discussed the current research that aims to support individuals living with dementia without medication, and whether these are effective or not. Examples of these therapies include music therapy and aromatherapy and we discussed how to “trial” these. The aim was for the audience to apply the knowledge learnt in the first half to the content and the activities in the second half.

Group Discussions

After the teaching took place and in the second half of the workshop, we invited individuals to join “break-out rooms” on Zoom, and those in person were in groups sat round tables. We had 3 vignettes for groups to discuss for 5 minutes, about how they would best manage a situation, applying the knowledge they had just learnt. We then invited individuals to share their ideas and perceptions. It was incredible to see how different perspectives and life stories enriched the discussion and inspired others. An example of a vignette is below.

How would you manage?

86-year-old widow lives with her daughter. She has a 3-year history 3 of Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD). She is currently on Donepezil for her ADD. She spends the day looking for certain clothes in her wardrobe and leaves some of these strewn around the bedroom and lounge. She accuses her daughter of theft as some of her clothes are missing. She repeatedly calls the police on her daughter. Her daughter repeatedly challenges her mother that she has no need of her mother’s clothes as they don’t fit and not her style.

Post-Workshop Reflection

A supportive environment

It was great to have such an interactive audience and individuals who were keen to get involved to raise points of interest and ask questions. It can always be a worry when asking the audience to get involved – but we had some great feedback and interaction from the audience which I was very grateful for!

Personal and Professional Growth

As the facilitator, witnessing the resilience of caregivers and healthcare professionals as they shared personal experiences was inspiring, and the huge interest in the workshop demonstrated how dementia-related psychosis affects so many people. For me, this has reaffirmed the importance of researching this topic.

Participant Feedback

The feedback received from participants following the workshop was incredibly rewarding. Many expressed how the experience had helped shape their approach to caregiving and had provided useful information in their supportive roles for people with dementia.

Conclusion

Hosting the workshop was an experience I thoroughly enjoyed. It was great to know the work you have put into researching receives appreciation from people who are directly impacted by the condition. It has helped me to understand the need for further research in this area, and I look forward to more opportunities to contribute to research and make a difference.

If you would like a copy of the recording or the slides of the workshop, please email Alice Burnand – a.burnand@ucl.ac.uk.

Acknowledgement

This research project and workshop were funded by the School of Primary Care Research at UCL. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Working as a Community Researcher on the Brent Integrated Care Partnership

By Eleanor Mason, on 4 October 2023

A blog from Community Researcher Sean Chou in his own words.

‘It’s important to get feelers out there and really get to know the community.’

At the beginning, I felt nervous about being a community researcher. It was a role that I was keen to get stuck into – having studied Anthropology as an undergraduate, I felt equipped with the curiosity and listening skills needed to glean insights from residents. But it was also one that I really didn’t want to get wrong. What if I said something offensive? What if I came off so keen to chat that it came across as awkward?

All of these doubts were soothed by the words from my research supervisor, Tamsin. I had regular weekly catch up meetings, as well as one-to-ones, where I had a safe space to share feedback on research and how I felt during research. It felt humanising to acknowledge that research has a person-centred approach, that the researcher themselves could have fears or internal doubts to reckon with.

But it was Tamsin’s personal touch that lit a flame in me. Tamsin had a keen interest in sustainability and building resilient communities with environmental solutions, and I was impressed to see how an interest in helping the local community in Brent could be knitted together with one’s own vision for what a better society could look like.

For me, that was about the community helping to lead change. Our research project looked at health inequalities in Brent, as well as how residents used community assets to tackle these inequalities. These went beyond just the ‘obvious’ physical assets – libraries, parks, civic buildings, to include the ones the communities valued themselves. Partnerships, mutual aid groups, classes, all of these are relationships that tie us together and ultimately make up who we are as holistic, social beings, rather than atomised, individual units.

This is especially the case [for our?] health. I attended community events organised by Brent Health Matters (BHM) which aimed to promote positive health outcomes, healthy living as well as register and signpost attendees to health and medical services such as GP registration.

I was able to see how attendees were tied together – or sometimes not, and sometimes made vulnerable, by their health: a mother with two children attended an event, not speaking English, but helped by my fellow researcher to translate her symptoms so the GP could make the right diagnosis. A woman who attended a floristry class saying that she attended because this helped with her mental health and make friends; if she wasn’t here today, she didn’t know what she would be doing. A night shift worker opening up to a BHM health worker about diabetes in her family, before breaking down crying about her family in Bangladesh. As I watched her be taken away by the health worker to talk somewhere more private, away from prying eyes, I was reminded of how health is a sensitive, emotionally charged experience for people. When we’re told by someone we love that we’re unhealthy, it often comes off as judgement – ‘You’re not doing enough to get healthy, you’re slacking’. But our physical health is often entangled with work, family, caring responsibilities that make it difficult to recentre our lives around living healthily.

But it also reminded me that some groups are more susceptible to poor health outcomes than others – those with low incomes, women, community groups, those from migrant backgrounds. BHM targeted these groups by bringing events to them. Community centres, places of worship, football pitches, food halls – all of these were places used to bring health services and awareness to communities, and ultimately bring communities together.

I was fortunate enough to be able to connect with the Chinese community. As a British Taiwanese person myself, I felt well placed to strike up rapport with those active in the community working across many different charities and local venues. I had conversations in Mandarin Chinese and bonded with members of the community over shared cultural festivals and cuisine. But I could also make sure that research was done for and by us, not just about us – in interactions and interviews, I made sure to emphasise the importance of residents’ views and ensure that research was led by residents’ interests from the ground up.

I am proud then to call myself a community researcher. From my experience, I have been able to connect my personal background with relationships that structure people’s wider access to healthcare. It remains vitally important that such work, centred on lived experiences, recognising others, listening to in-depth stories, continues through participant observation and interview research methods. Throughout my time as a community researcher, I’ve learned how to approach residents with empathy and curiosity, learned to tap into their views with interviews and produce data that represents the multi-dimensional, complex lived experiences residents have. Such data underpins ultimately why it’s so important to conduct community research, to see the people we study as holistic beings made up of different commitments and relationships, but ultimately brought together to be with others and lead a good life.

Want to find out more about the experience of our Community Researchers? Take a look at this zine by Sarah Al-Halfi.

Humanitarianism – what does it mean today?

By e.schaessens, on 18 August 2023

On World Humanitarian Day, Dr James Smith, Lecturer and Co-Director of UCL’s MSc in Humanitarian Policy & Practice reflects on the evolution of the humanitarian landscape and some of its inherent challenges.

The United Nations have stressed that the number of people requiring immediate ‘humanitarian assistance and protection’ has never been greater than this year. In the absence of concerted action, the impact of violence, widespread lack of access to essential public services, and wilful political indifference and neglect will continue to generate catastrophic levels of human suffering and ecological damage.

If we define humanitarianism in its broadest sense as a belief in the equal value of human life and a concern for human welfare, then the need for some form of humanitarianism appears as urgent as ever.

At the same time, popularised expressions of humanitarianism have shifted and changed over time. Humanitarian values have been institutionalised and bureaucratised, and corresponding systems and sectors have formed and grown. Now-dominant forms of humanitarianism have histories and contemporary articulations that are intimately tied to capitalism, colonialism and whiteness. Relatedly, criticism of the humanitarian system and its interventions has increased exponentially in recent years, driven forward by scandals that detail abuses of power, the undignified treatment of people in vulnerable situations, and a failure to enact the radical changes needed to alter how financial support is generated and distributed, or the means by which communities can take control of their own decision-making.

The growing number of instructive critiques of humanitarian action should inspire us to identify new ways to teach, study, and enact humanitarian values. It is increasingly clear that existing institutions, systems, and processes need to change and adapt in order to practice an ethics of care and concern. At the same time, calls for transnational solidarity (consider, for example, the vibrant civil society movements that pressed for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines), and global resource and knowledge sharing, are strong. The fundamental values that define humanitarianism can support and amplify these calls.

With UCL’s new MSc in Humanitarian Policy & Practice we are enthusiastic about working with students and professionals that are representative of the current and future global humanitarian workforce in order to think creatively and critically about humanitarian values and ethical and effective forms of humanitarian action. In doing so we will ensure students have the ability to develop programmes while continually interrogating foundational values, principles and motivations, and to design research studies while thinking critically about the politics of knowledge production, alongside several other priority topics.

By taking these steps we hope to contribute towards future humanitarianisms that enact a concern for our shared welfare in a way that is equity oriented, justice motivated, and solidarity driven.

Exploring barriers to equitable participation in health research among ethnic minorities: A co-production workshop

By Eleanor Mason, on 16 November 2022

Written by Camilla Rossi, Jo Blodgett, Chandrika Kaviraj, and Aradhna Kaushal

The way we research health matters. Despite a growing awareness of stark health inequities across the UK, most health research does not involve people from ethnic minority groups. This under-representation not only hides the experiences of those who are often most at risk of poor health, but it also prevents appropriate solutions from being developed. Through a UCL Research Culture Award, we organised a co-production workshop in London to better understand what might prevent equitable participation in health research and how to start addressing these barriers.

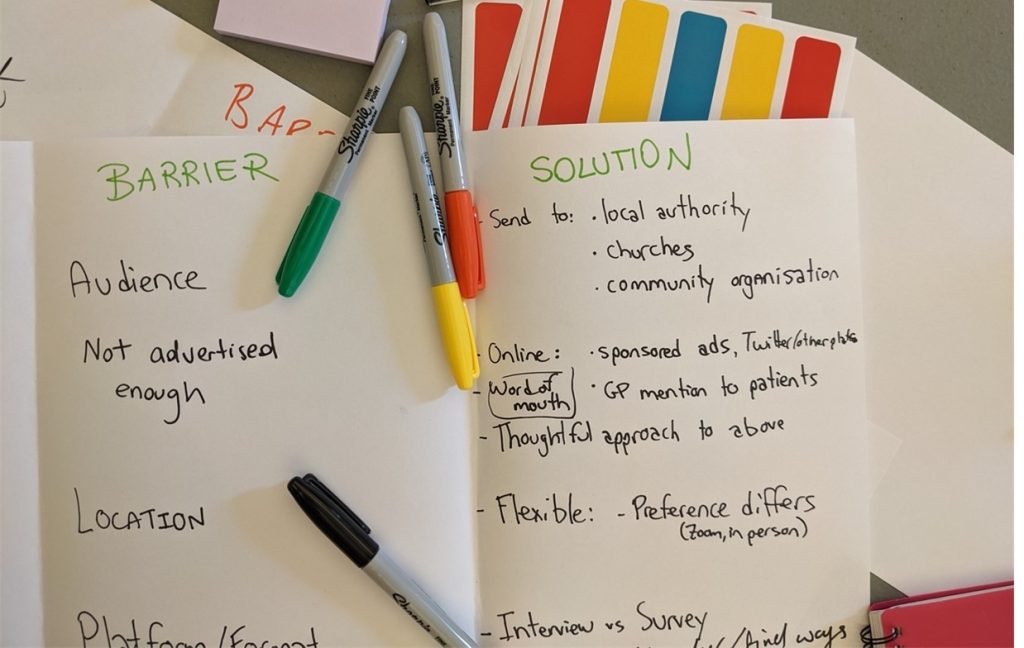

The workshop was held in June 2022 at UCL and brought together a group of six participants who identify as ethnic minorities. The activities developed around two main sessions: in the morning, the group brainstormed potential barriers to participation and discussed when they might emerge; the afternoon was dedicated to considering how they could be addressed, discussing the practicalities of involving people from different ethnic minority communities.

The project was informed by the notion of ‘knowledge co-production’. Through this approach, the researchers step back from their traditional role as ‘experts’ to make space for lived experiences as central forms of expertise. One of the ways we did this was by designing the workshop in collaboration with a member of the public, Chandrika Kaviraj. Chandrika reviewed and informed our initial proposal and is now overseeing the analysis and communication of the findings.

What is preventing equitable participation in health research?

Drawing from their families and their personal experiences, the participants identified a variety of potential barriers which we grouped under three main categories.

Lack of trust in institutions and their representatives emerged as a key underlying theme. Participants discussed the effects of “previous negative experiences”, “fear” of institutions and of the repercussions of getting involved, and shared a general perception that medical professionals and researchers are not trained to engage with racism and the trauma it causes:

“My mom would have so much to add to and learn about health research, but she is so deeply scared of institutions because of how she has been treated in the past.” (British Asian, male, 18-29)

Language and socio-cultural obstacles experienced within the health sector were identified as often concurrent, leading to a difficulty in communicating and being heard from both a linguistic and cultural point of view. This can contribute to a sense of “being invalid”, “incorrect”, and “uneducated”:

“Due to language barriers, due to feeling like it is something we’re not a part of, and due to doctors not understanding the cultural context … this leads to an inability to express.” (Black British, female, 40-49)

Practical barriers contribute to people perceiving health research as “not doable” or “relevant”. These can include lack of time and childcare needs, as well as the use of technology and the location of the study.

It is important to stress that the term ‘ethnic minorities’ includes a highly varied population, with ethnicity being only one of the many social categories shaping personal and social identity: different barriers might be more or less relevant to certain individuals or communities depending on factors such as gender, age, disability, or socioeconomic status. Engaging with this diversity and fluidity of experience is essential to avoid simplistic representations which may end up reinforcing the very barriers we are trying to dismantle.

What are the possible solutions?

Participants agreed that all barriers are exacerbated by researchers’ lack of knowledge and engagement with communities. This leads to research methods that do not fit with people’s lived experiences and needs.

The group developed four main recommendations.

- Tap into existing community structures

Researchers need to go beyond “traditional means” to make the research meaningful and relatable to people. Engaging with existing community structures and “physically going out there” was highlighted as essential. When the researcher has no existing links with a particular group, the involvement of a community member in the design and development of the project was recommended.

“You need more of a ‘community development mindset’: use the local authorities and look for places where people are already involved. Go out there.” (Black British, female, 40-49)

- Be transparent about the research aims, objectives, and challenges

The aims and objectives of the research needs to be communicated with clarity and transparency from the beginning: how can the research add value to their communities, families, society? What impact could it have and what are the limitations? Participants agreed that being transparent about the potential challenges involved might help to build trust, making researchers easier to relate and resonate with:

“These communities can smell fraud from miles: be honest about the barriers involved, we can relate to your constraints! If you manage people’s expectations, they will respect you more.” (Black British, male, 50-59)

- One size does not fit all: make the project flexible and adaptable

Investing time and resources into tailoring the research process was highlighted as essential both to encourage people to participate and ensure that they are not forced to drop out. Participants recommended advertising the study through different means of communication, both online and offline, hosting the study in safe and inclusive spaces, dedicating ample space for questions, and being ready to allow time, space, and support for participants struggling to commit for personal reasons:

“Show support and availability, the whole process needs to be more adaptable, flexible, and caring… which also means labour intensive!” (British Asian, male, 18-29)

- Bring the results back to the communities

Confining the research findings to academia can widen the gap between participants and the researcher, discouraging people from taking part in future studies. Instead, diversifying how research is communicated, including accessible reports and in-person presentations within community settings, could contribute to strengthening trust and generate new opportunities for engagement:

“The research needs to get back to the public who participated, they cannot be forgotten. Otherwise, they won’t participate again, and mistrust will continue.” (Black British, female, 40-49)

Next steps

The results of this project will be written up for publication in the coming months with plans to disseminate the findings widely across UCL, and beyond and to embed the learnings into relevant courses and teaching practices.

If you are interested in finding out more about this project or would like to be kept informed about future development – please email research.involvement@ucl.ac.uk

Teams of the Year Awards– a spotlight on secrets of successful teamwork

By guest blogger, on 1 June 2022

These are new awards introduced by the Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care Equality Action Group. Our work usually focuses on how to remedy problems – we wanted to find a way to spotlight and learn from teams which are successful in terms of productive, rewarding and enjoyable teamwork.

These are new awards introduced by the Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care Equality Action Group. Our work usually focuses on how to remedy problems – we wanted to find a way to spotlight and learn from teams which are successful in terms of productive, rewarding and enjoyable teamwork.

Team of the Year 2021

The Primary Care and Population Health (PCPH) Professional Services team won the award for Team of the Year 2021.

This is a large team (15 people) – congratulations to all of the members!

Orla O’Donnell – Site Manager and IEHC Finance lead

Ione Karney – PCPH HR and Finance administrator

Angelika Zikiy – Teaching Administrator Group lead

Sandra Soria Medina, Wahida Mizan, Dayan Soto Castellon and Diana Kwan – Teaching administrators

Rosemary Koper – Teaching Finance administrator

Jess Nye – Senior Programme Manager

Jeshma Mehta – Research Manager

Clare Casson – Project Manager

Becca Bayliss – Public Mental Health Network Coordinator

Sophia Hafeez – Research Group administrator

Bijal Parmar – Research Finance administrator

Ayan Robleh – IEHC Finance administrator

Amy Kerin – Clinical Trial & Research Design Service Administrator

What are the secrets of this team’s success?

Excellent collaboration

The PCPH professional services team work consistently as an excellent team, building on each other’s strengths and knowledge and working together collaboratively to achieve seamless service. They take on additional work for each other in order to meet goals and targets, and have been willing to work across the Institute in periods of staff absence and on new projects.

The team has formed a very strong bond over the past year and have been resilient during periods of change. They are a large team (15 people) which with members always willing to spend time sharing knowledge.

Communication

The team has ‘leads’ (e.g. HR, Finance, Research) and members work together, drawing on each other’s knowledge and expertise to problem-solve. Any problems are addressed collaboratively and immediately with those involved. We discuss what we have learned, to prevent problems happening again in the future. There is a no blame culture and this positive style of communication and collaboration trickles out into the wider department. There is no enforced ‘hierarchy’ culture within the team which means that junior members of the team feel supported and enabled to work as ‘One PS’

Shared learning

Knowledge and expertise is shared and valued regardless of whether team members have been in the department for many years, or have only recently joined.

Vision and flexibility

The team shows wisdom, flexibility and creativity, and strong team playing to meet shared objectives. The PS team also understand the bigger picture – the team worked consistently and without complaint in order to deliver on wider goals as a Department.

Most Valued Team Player Awards

Larisa Dinu won the ‘Most valued team player 2021’ award.

Larisa is a Research Assistant in the Department of Behavioural Science and Health. Below are a few comments from Larisa’s colleagues and Larisa herself.

“Larisa is delightful to work with, friendly, helpful and proactive”

“Larisa can see where things can be improved and identify ways to solve problems. She has noticed ways of improving our existing systems, so that a lot of day-to-day tasks are now running much more quickly”

“Larisa is very thorough and diligent in her work, and is quick to pick up on tasks to help out other members of the team. Larisa is an excellent communicator – all her emails are very clear, meaning other team members can perform necessary tasks quickly and efficiently”

Comment from Larisa:

“I am extremely grateful to have won the ‘Most valued team player’ award, and would like to thank my team, the iDEAS trial team, as well as the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group for fostering such a collaborative and engaging environment to work in. It is truly a pleasure to work with such a fantastic group of people.

I am a keen advocate for lists, combined with flexible time-blocking of the most important three tasks of the day which is helpful in creating a rough structure for my days. I also like to separate deep work tasks and meetings if that is possible, to minimise task switching.

Being a team player is not just about me, but also about the amazing people that I work with, and processes which facilitate collaboration. For example, we have weekly meetings with the whole team where we share updates and take decisions collaboratively. We also have regular updates between ourselves, and communicate efficiently either via video calls or email. This helps us to know what everyone else is up to and gives us the opportunity to provide feedback and offer help.

I find my work very rewarding, especially when we see the impact of our work in the real world.”

Sydonnie Hyman was runner up for the ‘Most valued team player award’.

Sydonnie is the IEHC Deputy Manager and Human Resources Lead.

“Sydonnie Hyman is a very responsive, helpful, and effective person! She has driven the Equality Action Career Progression group through the pandemic to great success, with a career development cycle, a mentorship scheme and a careers week amongst many other innovations.

Sydonnie has encouraged new members to join the Career Progression group and take on leadership, helping other people’s career development as well as enhancing the activity of the group. Sydonnie is also sensitive to people’s personal challenges”

Congratulations again to all of the winners!

Julia Bailey (Equality Action Group Co-Chair)

May 2022

Fuel and Food Poverty in the UK must be addressed before the energy price hike this Spring

By e.schaessens, on 18 January 2022

Written by Rebecca Barlow-Noone, a student on the MSc Population Health programme.

During the pandemic, inequalities in the UK have been brought into sharp relief with a rapid rise in food and fuel poverty, which I documented last year and have seen first-hand as a volunteer for Lambeth Foodbanks. Yet with fuel price caps set to skyrocket in the coming months and no plans to protect those on low incomes, it is likely to push even more people below the poverty line, forcing many to decide whether to ‘heat or eat’.

During the pandemic, inequalities in the UK have been brought into sharp relief with a rapid rise in food and fuel poverty, which I documented last year and have seen first-hand as a volunteer for Lambeth Foodbanks. Yet with fuel price caps set to skyrocket in the coming months and no plans to protect those on low incomes, it is likely to push even more people below the poverty line, forcing many to decide whether to ‘heat or eat’.

Foodbanks during the pandemic

Compared to 5 years ago, Trussell Trust food bank demand has increased 128%. Between April 2020 and March 2021, 2.5 million emergency food parcels were delivered in the UK by the Trussell Trust, representing a 33% increase from the previous pre-pandemic year. Furthermore, in December 2020, high levels of child food poverty in London led to additional food parcel distributions by UNICEF. This is despite the £20 per week Universal Credit (UC) uplift introduced in March 2020 in response to the pandemic.

The effect of Universal Credit cuts, energy price hikes, and inflation

As winter approached in late 2021, people on UC saw the tightest squeeze yet. The benefits uplift was cut, leaving recipients £1,040 per year worse off; prepayment energy tariffs saw the highest price increase of £153 to £1309 per year, which is used more by those on low incomes than high incomes; and inflation hit a 10-year high. While a taper rate of UC was implemented shortly after the uplift was cut, this only benefitted claimants who were already in work, and did not apply to people receiving legacy benefits.

I am deeply concerned how rising fuel costs this April will affect those already feeling the effects of the cut and price cap increase. When speaking to clients, I often hear how hard it is to make ends meet. I hear from parents forgoing meals for the sake of their children, and elderly clients unable to pay the higher energy bills through the winter. This is only set to get worse, with Age UK estimating that fuel poverty in the elderly may reach over 150,000 without financial protection this spring. It is unacceptable for people to be treated so poorly in a wealthy society such as the UK, at a time when they need the most support.

As costs of living increase for all, now is the time to increase support for those whose incomes at current UC rates do not allow for basic standards of living. Foodbanks across the UK represent an important lifeline, but this cannot be considered the norm and should not be relied upon by Government. The current rise in food bank reliance and the impending rise in fuel costs demands scrutiny into the social policies that are failing to adequately support those in need, to ensure those at most risk are protected from the increasing fuel price cap.

Close

Close