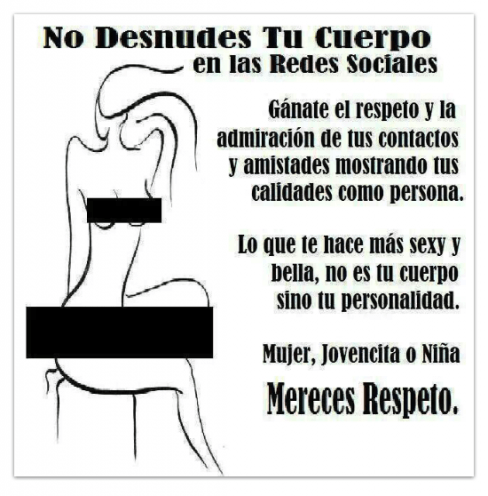

Last week, a friend here in Northern Chile posted on his Facebook wall a stylized drawing of a woman’s body with the words: “Don’t show your naked body on social networking sites. Gain the admiration and respect of your contacts and friends by showing your qualities as a person. What makes you sexy and beautiful is not your body, but your personality. Women and girls deserve respect.”

This was not the first time I had seen such a post. I have seen such memes circulating for several months, posted by grandmothers, mothers, and young men and women. But this post made me pause because my friend Miguel was the one who posted it. A few months into my fieldwork, Miguel was showing me a funny meme his friend had posted. As he scrolled down on his Facebook feed, he passed a post from Playboy Magazine that showed two women in bikinis. “Oh, those are my ugly cousins!” he joked. As he scrolled down there were several other posts from Playboy and he told me “My cousins post pictures of themselves a lot.”

Since the subject had been breached, he seemed to feel comfortable discussing semi-pornographic posts with me and I took advantage of the situation by continuing to ask questions. He told me all about “the new thing” of pictures of the underside of women’s breasts rather than their cleavage. He switched to Whatsapp and clicked a link a friend had sent him to demonstrate. There I saw “50 of the Best Underboob Shots on the Internet,” mostly taken selfie-style either in the mirror, or up one’s own shirt. I wasn’t sure whether to be offended or confused.

With this previous discussion in mind, in which, quite openly he discussed how he enjoyed seeing overtly sexy pictures that women take of their bodies, it seemed strange that he would post such a meme chastising women for doing this very thing.

Of course, there is a big difference between the women who are likely the intended recipients of his message and the women who are displayed on Playboy’s Facebook page. That is: he expects his female friends to read his Facebook wall. He does not expect Playboy models, or even the women whose reverse cleavage pictures are floating around the internet to be his followers on Facebook. In essence, his Facebook activity is revealing of something anthropologists have long known; we treat friends and acquaintances differently than we treat strangers (for example see Simmel’s essay on The Stranger and our own blog about chatting to Strangers in China). In this case it is acceptable to objectify the bodies of strangers, but he hopes that the women he knows personally will not openly contribute to their own objectification.

In looking through my own female Facebook friends from Northern Chile, I don’t see any pictures that are overtly sexual and show body parts that one wouldn’t reveal on a hot summer day. However, in my “you might know…” suggestions, I do see several such profile pictures for accounts based in this city. Miguel, along with other friends—both male and female—assured me that these profiles were fake (see also controversies of fake profiles in India and Turkey). “They say they’re from here but I’ve never met any of these women. They’re definitely fake profiles.”

To me this suggests two related points about the ways the regulation of bodies and nudity are happening online. The first is simply that these “Don’t show your naked body” memes represent a way of surveilling and controlling what others do with their bodies. They use straw-women as a warning, suggesting that showing too much body on social media will result in people losing respect. This strategy seems to have worked as well. Young women in northern Chile shy away from showing their bodies in contexts connected to their public personality. Yet the pictures still appear in the form of anonymous or fake profiles. Using fake names and profile pictures, they still post faceless photos exposing body parts fit only for a very liberal beach.

While this in some ways may be seen as a victory for young women’s self-worth based on traits not connected to their sexuality or bodies’ likenesses to those featured in the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, the surveillance and judgment of their online activity represents another issue—regulation that denies young women agency over the representation of their own bodies. This is one thing when coming from mothers and aunts, but young men like Miguel present a double standard in which their social networking activity elevates the bodies of strangers—from swimsuit models to unknown women taking risqué selfies, while condemning their own peers for similar self-representations. It’s not hard to imagine then why fake profiles might be a good option for young women trying to find self esteem about their bodies and their own ways to fit into the world of social networking.

In the end, what this tells us about social networking sites in this context, is that they are still very closely connected to the body. The internet is not a haven for free-floating identity, disconnected from our physical form, but is a place where bodies may still be seen as a representation of an individual, may still be regulated, and may still be a site of agency or repression. Rather than actually showing the respect that “women and girls deserve,” these memes further regulate women. Much as catcalls on the street regulate women’s bodies in physical space, memes that tell women what is acceptable for their bodies do so in the space of the internet.

If you are interested in themes of surveillance and control, see also Caste Related Profiles on Facebook in India, Facebook and the Vulnerability of the Self and Love is… in Turkey, and Social Media and the Sense of Autonomy in Italy.

Filed under Anthropology, Chile, Parenting, Politics, Privacy

Tags: anthropology, Chile, ethnography, Facebook, family, gender, photography, privacy, public, social networking, surveillance

2 Comments »

Close

Close