Is Weibo on the way out? For some in China, it was never in.

By Tom McDonald, on 11 May 2015

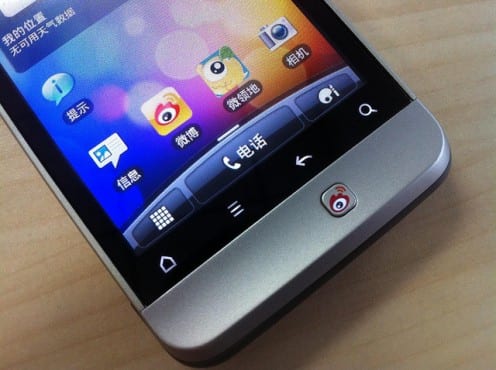

Weibo: share your thoughts with the world (assuming, of course, you actually want to). Photo: bfishadow (CC BY 2.0)

I read with interest Celia Hatton’s BBC News article published in February, which hinted that real-name registration on Chinese micro-blogging platform Sina Weibo may be the death knell for the social media platform, which Hatton claims was already losing popularity owing to increasing government control over the platform that was ‘once the only place to find vibrant sources of debate on the Chinese internet’.

Hatton’s argument is important and interesting, and it likely accurately reflects significant changes occurring in social media use in urban China. However based on my experience of carrying out 15 months ethnographic research on social media use in a small rural Chinese Town, it’s also worth bearing in mind that the situation in the Chinese countryside is very different from urban areas. China’s rural populations have tended to display little interest in Weibo.

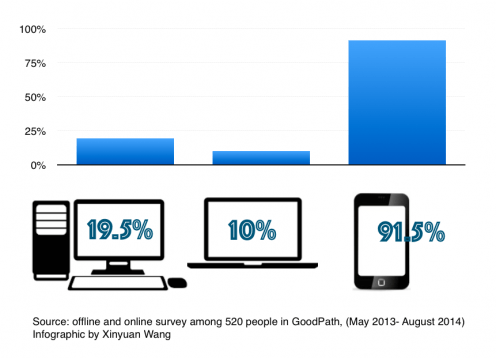

While Weibo has dominated much media and academic analysis of China social media, in reality ‘most microblog users are mainly young, urban, and middle class, and geographically concentrated in the coastal regions’ as research from Lund University has noted. A separate study (in Chinese) showed that only 5% of microblog users in China live in the countryside, despite the fact that 27.9% of internet users are rural residents.

Why did Weibo never appeal to rural users in the first place? People in the rural town where I conducted my study explained that they preferred social media platforms such as QQ (and to a lesser extent, WeChat) over Weibo. These platforms were popular precisely because they were ‘closed’ platforms, where people could share things only with their friends – most of whom were people they knew in their hometown. For these people the thought of sharing their postings with the entire internet held no appeal whatsoever.

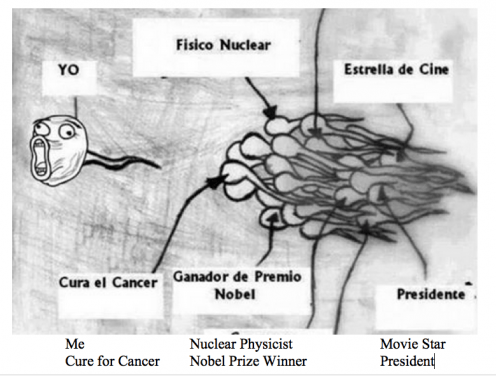

These findings are interesting because they appear to challenge assumptions that people – especially the those at the bottom of Chinese society – would naturally desire to use the internet to ‘express themselves’ to the rest of the world. Rather than presuming that social media are destined to be technologies of liberation, such accounts highlight the importance of also paying attention to how technologies are actually used by rural Chinese people within the context of their own lives, where they are often put to use towards achieving aims and aspirations that may differ greatly from those we expect of them.

Close

Close