Everyday salutations such as ‘Good Morning’, ‘Good Afternoon’, ‘Good Evening’ etc. are common social media interactions of the people of Panchagrami, used to keep in touch with an already established group of friends. Interviews with informants revealed that once they have an established group of Facebook or WhatsApp friends, maintaining engagement with everyone becomes important. Otherwise, people are troubled by the question of what to do with an accumulated capital of friends on social media. In order to circumvent this, everyday salutations are a way to keep their friends list actively engaged in a positive and non-confrontational way.

However, these kinds of messages are not only seen as a practice of building sociality and maintaining touch with an accumulated group of friends. They are also used for accruing positive karma points, which have a religious connotation. Several middle-aged informants from Panchagrami participate in religious activities on Facebook and even if they don’t categorise this as activity related to religion, it is always related to building good Karma, stemming from a Hindu belief that what goes around comes around and that good actions lead to good outcomes. Participation can range from posting pictures of Gods, posting religious messages as a positive message for self development, sharing inspirational poems, stories etc. as a way of giving positive reinforcement to society, which can then build good Karma for the giver/poster. People even follow this as an everyday routine, as in the case of one of my informants, Vidya Shankar.

Vidya Shankar, a 47-year-old architect, feels that since most of his social circle is on Facebook, he can use his social circle as a set of ready audience to build good Karma for himself. He maintains a routine of posting an image of a Hindu god (mostly that of Krishna or Ganesha) on Facebook before 6 AM everyday.

Fig 1: Vidyashankar’s image of Lord Krishna

Vidya Shankar sticks to this routine, since he knows that most of his middle-aged Facebook friends will check Facebook when they wake up every morning. So, in order to ensure that they wake up to an auspicious symbol, he makes sure to post an image of a Hindu god on his Timeline just a little before 6 AM.

Vidya Shankar says: “I know people have checked it when I start receiving ‘Likes’ immediately after I post…its mostly the same set of around 40 to 45 friends of mine, but receiving immediate feedback is effective, since I know that I have built the necessary good Karma for the day and I am sure that as they “Share” it with others, it will not only help build their Karma, but also mine, as I help build theirs”.

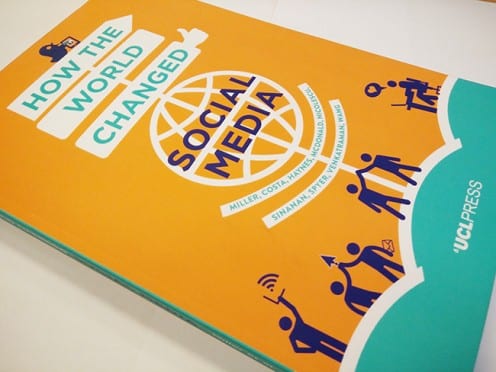

Sudhasri, a 39-year-old housewife, builds her Karma points by posting positive messages every morning on a WhatsApp group with about 35 members. She posts a positive saying adapted from a religious book along with a “Good Morning” message to this group. Sudhasri says: “My messages can help people start their day on a positive note, since even getting up in the morning is a miracle and I don’t want people to waste their god given day…a positive start can help have a joyous day…I have done something good for the day then”.

Fig 2: Sudhasri’s prayer on WhatsApp group

Vidya Shankar and Sudhasri aren’t alone, as several informants believe that routinely participating in giving goodness to society (their immediate social circle on social media), can help reap good Karma.

Filed under Anthropology, India, Sharing our findings

Tags: Facebook, Hindu, Karma, Lord Krishna, Positive, religion, Salutations, social media, South India, WhatsApp

Comments Off on Build Karma Points on Social Media

Close

Close