Blog by Carrie Behar, UCL-Energy PhD student

Get invovled in the conversation: Follow Carrie on Twitter – @LoLoStudent

Being asked to prepare a blog post for this year’s climate week got me thinking about how my work relates to climate change. To me, climate change is a huge and scary thing. It feels totally beyond my control, and if I do spend too much time thinking about the magnitude of the problem, I feel like giving up altogether and running away to a desert island. The problem is, if we all did that, it would be only a matter of time before all the desert islands got full, that is if they weren’t first subsumed by rising sea levels.

desert island. The problem is, if we all did that, it would be only a matter of time before all the desert islands got full, that is if they weren’t first subsumed by rising sea levels.

Another problem with desert islands is their lack of high speed broadband, lively high streets with shops and bars, and comfortable spaces where I can sit and think and read and write, occasionally engaging in stimulating conversations with my colleagues, or grabbing a bite to eat in a local café. Furthermore, much as I like the idea of spending my evenings lying in a hammock under the stars, I also thoroughly enjoy my own personal routine of waking up in a warm and comfy bed on a Saturday morning and then wasting an hour or so playing on Twitter whilst building up the motivation to face the gym!

So here I am, and here are lots of us, living our lives very much within the constraints of the culture within which we were born and raised. We live in heated (or cooled) houses and flats, eat food imported from all over the world, travel longer distances that we feel comfortable with to get to work or school, and spend much of our time indoors, usually connected to some kind of electronic device. And all of these activities, consume energy – lots of energy. This energy that we rely on to live our ordinary lives is generated from a combination of burning of fossil fuels and utilising renewable resources such as wind and solar. And it is the burning of fossil fuels that is accelerating the changes we are seeing in our climate, as explained here.

of these activities, consume energy – lots of energy. This energy that we rely on to live our ordinary lives is generated from a combination of burning of fossil fuels and utilising renewable resources such as wind and solar. And it is the burning of fossil fuels that is accelerating the changes we are seeing in our climate, as explained here.

What can energy demand research do to help?

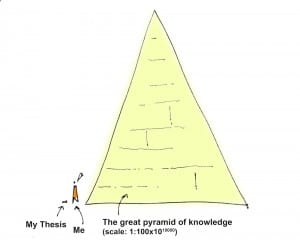

Ultimately, the reason I am here, doing my PhD and writing this blog is because, recognising the contribution of energy consumption in buildings to changes in the world’s climate, the UK Research Councils felt it was worth providing funding for PhD research in both energy supply and use. But what am I actually doing and what do I hope to achieve? And can I really make a difference with my tiny contribution to the vast pyramid of knowledge?

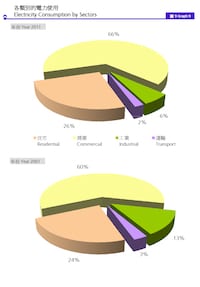

At first glance, looking at how people are adapting to living in new low-energy homes with ‘whole house’ ventilation systems is a long way away from working on ‘solving’ climate change (more about my work here). However, if we understand that energy used in our 27 million homes accounts for nearly a third of total UK energy use, it’s at least clear that there is a strong need to reduce the energy consumption of both new and existing dwellings.

As around 60% of domestic energy use can be attributed to space heating, an effective way of achieving this reduction is to seal up gaps and cracks around windows, doors, floors and roofs to make our homes more airtight and less draughty, thereby keeping the heat in. However, we cannot completely seal up homes, because the activities we carry out inside them generate a range of pollutants which need to be removed. Ventilation is the controlled provision of clean air and the removal of stale air, which typically contains CO2 exhaled by people, water vapour from showering and washing, and smells generated when cooking. These byproducts of ever yday domestic activities must be taken out to keep us healthy and prevent nasty things like mould developing.

yday domestic activities must be taken out to keep us healthy and prevent nasty things like mould developing.

Why technologies alone won’t fix the problem

Several technical solutions have been proposed to deal with the problem of ensuring sufficient ventilation without wasting any heat energy. These are explained in detail in this Energy Saving Trust publication. The idea is that, during winter, air is only permitted to enter and leave through designated and controlled openings, such as trickle vents and ceiling extracts. The house stays toasty and warm, while harmful pollutants are removed and replaced by fresh air from outside. Problem solved, right?

Unfortunately not. Although these systems have potential, the deployment of technology is not in itself a guarantee of success. Monitoring of energy consumption at completed homes which incorporate these systems repeatedly highlights the large gap between predicted and actual energy consumption. There are a number of factors that contribute to this performance gap and the way that people use and interact with their homes is but one of them. That’s not to say that people are necessarily doing something wrong; rather, there are a wide range of normal activities that we carry out which can impact on energy use. For example, do we regularly cook for family and friends or eat out most nights? Do we prefer baths or showers? And how much time do we spend at home and at what temperatures do we feel most comfortable?

When recommending, specifying or installing a specific ventilation system, there is an inherent assumption that the people living in the house will act in a certain way to get the best use from their technology. The ‘model’ resident would leave the windows closed at all times when the heating is on, and rely on the ventilation to do its job. They would press the booster button each time they cook or shower, and only dry their clothes on the designated drying rack in the bathroom. Furthermore, they would make sure the extract vents were kept free of dust and grease and ensure that filters are changed regularly so that system performance does not deteriorate.

We won’t improve anything without understanding people

Unfortunately this assumption fails to acknowledge the day to day realities of life. Very few of us go about our existence worrying about the energy consequences of our every activity. If we did, we would get very little done and end up a bit mad (and start thinking about desert islands and the like…).

Although you cannot, rightly, force people to behave in a certain way, I would like it to become easier for people to do the most efficient thing, and in the case of domestic ventilation I think we have a long way to go before this is the case. Over the course of my studies I have met people who are largely unaware of the presence of controlled ventilation in their home, let alone knowing what to do with it, as well as a family with a broken booster button who had no option but to open the window to let out cooking fumes.

Although you cannot, rightly, force people to behave in a certain way, I would like it to become easier for people to do the most efficient thing, and in the case of domestic ventilation I think we have a long way to go before this is the case. Over the course of my studies I have met people who are largely unaware of the presence of controlled ventilation in their home, let alone knowing what to do with it, as well as a family with a broken booster button who had no option but to open the window to let out cooking fumes.

Completely unsurprisingly, I am yet to meet someone who is able to explain to me correctly what MVHR, MEV or PSV are and how they work (and if you didn’t get round to reading the Energy Saving Trust publication I mentioned earlier then you probably don’t either!). The residents I have spoken to have never been told that there are filters that need changing, nor that they could save energy and money by keeping the windows closed when the heating’s on. The reality is that we open the windows and forget to close them, dry clothes on radiators, put off housework until it is absolutely necessary and we find a way round things like broken switches that doesn’t involve us calling a handyman.

And this is why, I believe, the problem of climate change is so hard to resolve. Society seems to be driven by a desire to invent technical solutions to fix problems. But when we break down the issue into smaller and smaller chunks, for example individual houses and their ventilation systems, we are always left with people and organisations interacting with material things in unexpected ways and not just the objects themselves. And it may just be that rather than relentlessly, modelling, simulating and optimising how technologies work, the solutions to global problems could lie in understanding how the minutiae of day-to-day life shape our energy use.

Carrie Behar

Close

Close