“Half the work, twice the effect” – from a Chinese proverb to the cost-effective responses to the climate crisis

By ucftaww, on 6 March 2014

Blog by Wenjia Cai, UCL Lancet Commission

Right now I am sitting in my office in Beijing, where the air quality has been labeled by “hazardous” for almost a week. I am suffering from my sore throat, but I have nowhere to escape.

I believe this is the kind of frustration faced by many people, when they know climate change is threatening their health. The negative health impacts are happening, and are very likely to cost us a fortune.

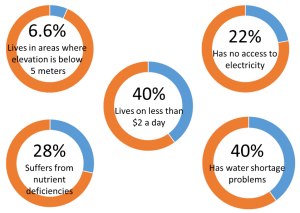

Some simple but serious facts [1]-[3] are shown below. Of the world’s total population,

These are the most vulnerable people in the world. They are never the biggest contributors to the climate change crisis, but they are the ones being affected the most. Their health has been greatly threatened by droughts, floods, hunger, vector-borne diseases, home damages and health services interrupts.

Take hurricanes and storms for example. Hurricane Sandy hit the northeast coast of the United States, causing widespread damage and around 100 people died. However, in the developing world, such storms take a much greater toll. In 2007 and 2008, two very severe storms – Sidr and Nargis – caused the deaths of more than 10,000 and around 138,000 people in Bangladesh and Myanmar, respectively. In fact, statistics shows that only 5% of tropical cyclones occur in the north Indian Ocean, but they account for 95% of such casualties worldwide[4].

To respond to the climate crisis, greenhouse gas mitigation certainly aims for the root of the problem; yet some simple and low-cost adaptation measures can have instant effects.

Peter J. Webster, a professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, USA, advocates for the establishment of network between the forecasters of global weather and climate in the developed world, and research, governmental and non-governmental organizations in the less-developed world[4]. He estimated that such a network could produce 10-15-day forecasts for south and east Asia for a wide range of hydrometeorological hazards (including slow-rise monsoon floods, droughts and tropical cyclones), which will cost as little as $2~3 million a year, but save billions of dollars and thousands of lives.

On the basis of a World Bank report[5], one analysis concluded that about $ 40 was saved for every dollar invested in the regional forecasting and warning system.

Fortunately, as commented by Webster, Bangladesh already benefited from such network. In 2007 and 2008, Bangladesh experienced three major floods. Each was forecast successfully ten days in advance and mitigation steps were taken.

This is one successful story of how we can quickly adapt to the coming climate crisis in a cost-effective way. The following table is excerpted from the major-task list of the “National Strategy of Climate Change Adaption” in China[6], published in November 2013, which may also provide us some hints on the other cost-effective options.

| Major tasks to protect human health under climate change context in China | |

| Improve the health and epidemic prevention system construction | –strengthen disease prevention and control system–amend the indoor and working environmental standards–monitor drinking water hygiene conditions |

| Carry out monitoring and evaluation, as well as public information services | –evaluate climate change impacts on the health of vulnerable people–establish the health-related weather monitoring and early warning networks, and public information service system |

| Strengthen the emergency system construction | –develop and improve the health emergency plans for heat stroke, snow and ice, haze and other extreme weather and climate events |

We are standing in the historic moment of addressing the climate crisis. Any delayed action may result in irreversible change and unaffordable costs. To make the right strategy, the traditional cost-effective analysis (CBA) can shed some light and help us choose within the large pool of adaptation and mitigation options. Obviously our choices will lean towards those options which don’t need high investment and will eventually pay for itself. In fact, there are many such options which can have the “twice the effect” with “half the work”. Our report will try to identify them. It’s also expected that, after considering the monetized health benefits, those options will become much more cost-effective, which can strengthen the will and catalyze the actions from politicians and investors.

Wenjia Cai is an assistant professor of Global Change Economics in Center for Earth System Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China. E-mail: wcai@tsinghua.edu.cn. The blog content only shows the views from the author, and cannot represent the opinions of any organizations or working groups.

References:

[1] World Bank, 2013. World Development Indicators 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/region/WLD (accessed Feb 25th, 2014)

[2] Da Silva J, 2013.. World Food Day 2013: Towards Sustainable Food Systems. http://www.fao.org//about/who-we-are/director-gen/faodg-opinionarticles/detail/en/c/203152/ (accessed Feb 25th, 2014)

[3] World Health Organization, 2013. 10 Facts on Climate Change and Health. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/climate_change/facts/en/index5.html (accessed Feb 25th, 2014)

[4] Webster P, 2013. Improve weather forecasts for the developing world. Nature, 493: 17-19.

[5] Teisberg TJ, Weiher RF, 2009. Background Paper on the Benefits and Costs of Early Warning Systems for Major Natural Hazards. https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr.org/files/New%20Folder/Teisberg_EWS.pdf (accessed Feb 25th, 2014)

[6] National Development and Reform Commission, 2013. China’s National Strategy of Climate Change Adaption. http://qhs.ndrc.gov.cn/gzdt/W020131213626583538862.pdf (accessed Feb 25th, 2014)

Close

Close