Climate Change and Water – A Link to Engender Action?

By ucftpdr, on 5 March 2014

Blog by Paul Drummond, UCL ISR Researcher

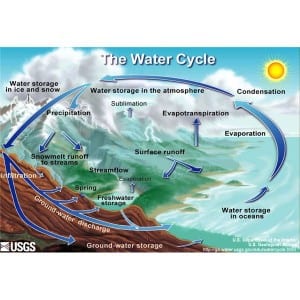

As is well known, the climate system and hydrological cycle are inextricably linked. A warmer atmosphere melts water stored as ice at high latitudes and altitudes leading to sea level rise, which in turn allows more of the sun’s radiation to be absorbed, further accelerating warming. A warmer atmosphere is able to hold more moisture, increasing the frequency of heavy rainfall events in areas of previously moderate conditions, whilst shifting climatic zones may either reduce the intensity and timing (or even remove) heavy rainfall in areas that rely upon it. Water vapour itself, of course, is the most prevalent greenhouse gas.

Might it be this relationship that eventually spurs the world into action to reduce emissions to prevent the worst effects of a changing climate?

It certainly seems possible. The recent drought in California and flooding in the south of England have both bumped climate change to the top of the political agenda in the USA and UK once more. The current Californian drought has so far lasted for nearly three years, with 2013 the driest year since records began. Reservoir levels are dangerously low, with fires running rampant across the parched landscape. The large agricultural economy has been hit extremely hard. The situation in the south and particularly south-west of the UK couldn’t be more stark. England and Wales saw the most winter rainfall since 1766, bursting river banks and overcoming defences to flood over 6,500 homes and around 50,000 hectares of farmland.

These opposing sides of the same coin directly impact the lives and livelihoods of people living and working in these areas. Naturally, they seek reasons for why this is happening to them, who is at fault, and assurances that all efforts will be taken to make sure that it does not happen again.

At least some of blame has been focussed on government policy. In the UK, a lack of dredging of rivers and inadequate historic investment in flood defences has been blamed, along with long-term trends of removing upland vegetation for pasture and expanding settlements onto floodplains (or even reclaimed land in the case of the Somerset Levels). Of course, these aspects all combine to a greater or lesser extent to produce the damage experienced. But such factors may only control what happens to precipitation once it has occurred, and not the volume that must be dealt with.

This is where climate change enters the present discourse. Of course, an explicit link between these specific extreme events and climate change cannot be drawn, however a changing climate is likely to increase the frequency by which these events occur, and their intensity when they do. Despite this, both President Obama and David Cameron have voiced their opinions that climate change very much had a role to play in recent events (or in Cameron’s words, ‘very much suspects’). Such rhetoric, particularly in the UK from a government who it was felt were abandoning their ‘green’ credentials over time, reflects the extent to which climate change, and whether and how we should tackle it, has re-entered the public debate.

Of course, the USA and UK are not the only states in which water issues can be prevalent. In many countries, the absence or abundance of water is of paramount importance – a concern this is only likely to increase over time. However, it appears that developing nations are over-represented among this number. For example, small island states and low-lying countries such as Bangladesh are likely to be the first victims of a rising sea level, whilst the nations of the North Africa are likely to be among the first to feel extended periods of chronic water shortages, in parallel to expected rapid increases in population.

Unfortunately, these are not the nations that hold the key to meaningful global climate action, and they broadly do not have the financial resources to adapt to their new climate regimes if such action is not taken. It is the developed nations, along with the BRICS, which are pivotal. It is only when these countries decide that mitigation action is indeed necessary that significant steps will be taken, and this is unlikely to happen until climate change ceases to be an abstract concept in the mind of the general populous, but a real and present issue – with the most likely manifestation of this to be when previously extreme flood and drought events become increasingly normalised.

Close

Close