Blog by Ian Hamilton, Lecturer and Senior Research Associate in Energy Epidemiology, UCL-Energy

Is there a benefit to our health from undertaking actions to mitigate climate change? The answer is complicated (as most things are), but generally speaking there are both potential benefits and risks to our health.

If we focus on buildings, where we now spend the majority of our lifetime in the UK, and in particular housing, there are a several mitigation actions that we might consider what the impact on our health could be. These include actions to reduce the heat lost by insulting and draught proofing the building fabric and powering our lives with low-carbon fuels.

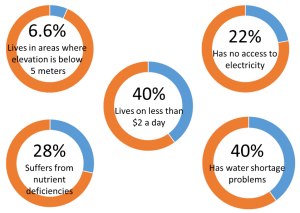

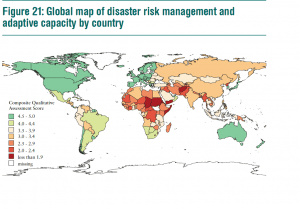

First, it is worth considering what a future of climate change could mean to health. In 2009, a joint UCL-Lancet commission explored the potential impact that climate change could have on health including: changing patterns and spread of disease, habitat loss and animal extinction and impact on food production, changing rainfall and drought that risks access to safe and clean water, infrastructure failure and access to energy, and the increased risk of extreme events. They noted that these events would lead to exacerbating inequality by increasing instability and competition for resources with most of the burden falling to the poor. The commission concluded that climate change was the greatest threat to human health of the 21st century.(1)

The UK has a large burden of excess winter mortality and morbidity (upward of 25,000 excess winter deaths EWD each year)(2), which is greater than that of many comparable northern European countries with colder climates(3). While a portion of winter excess is attributable to influenza and other seasonal infections, several studies have also suggested that a substantial part of the seasonal burden is still related to exposure to cold(4,5). Evidence from the UK, New Zealand and elsewhere does suggest that housing energy performance may play an important role in determining that risk(6,7) (i.e. inefficient homes are also cold homes). Though it should also be recognized that exposures to cold from excursions outdoors could play a role.

Improving our housing stock is a major part of the UK Government’s proposals of an ambitious strategy to reduce emissions from the building stock, which are part of its commitment to reduce UK greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80% by 2050(8). The Energy Efficiency Strategy(9) includes policies to reduce energy demand through improvements in building energy performance and aggressive decarbonisation of the energy supply system. Under these plans, the Government has set out pathways that will see millions of energy efficiency retrofits installed in houses by 2050 at an estimated cost of £200bn(10).

By insulating our houses, there are benefits of being better able to maintain a comfortable temperature and save money by reducing the energy needed to heat. It is recognised that following an efficiency retrofit, many households will take mixture of energy savings and improvements in indoor temperature(11). Whilst this action may result in less than expected energy (and therefore CO2) savings, evidence suggests that those actions have resulted in improved thermal comfort(12), mental wellbeing(13), and reduced mould growth(14). There may also be benefits from living in warm homes by reducing the risk to different diseases, including(15): cardiovascular, cardiopulmonary, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma in children.

There is a risk, however, that if the air tightness of a home is reduced and there is not additional ventilation, the action will increase exposure to indoor pollutants(16). A recent study in the BMJ highlighted this risk to health from radon gases(17). This preliminary work indicated that unless specific remediation is used, reducing the ventilation of dwellings will improve energy efficiency only at the expense of population wide adverse impact on indoor exposure to radon and risk of lung cancer. There are, however, many possible unintended consequences of actions to improve energy efficiency(18). To avoid these negative co-effects, more robust evidence, better policy formulation and actions to ensure effective implementation are needed alongside climate change mitigation.

A warmer climate may not even protect against cold related deaths. Recent work by colleagues at UCL has suggested that a future warmer climate may not reduce excess winter deaths(19) (EWD) (i.e. the excess number of deaths during winter months compared to summer months). By looking at past data from England and Wales, Staddon et al (2014) showed that cold days in winter was a strong driver of EWD up to the 1970’s and that improvements in housing, health care, have helped in reducing EWD. They suggest though that future warming in climate is unlikely to hold much benefit for reducing this health risk and the risk may be greater from more extreme weather events.

Decarbonising the power supply sector also holds both risks and benefits for health. The direct benefits centre on reducing exposure to air pollutants(20). In the UK, the associated burden of air pollution from the power sector is estimated to account for 3,800 deaths per year, related to respiratory illness(20). In places where emissions from the power sector are not well controlled the potential impact is likely much higher. The burden of disease in China related to air pollution is much higher than the European Union, with premature deaths from PM2.5 along at 7.4 times greater(21). This year, particulate matter in Chinese cities across the northern part or the country has been exceeding the WHO guidance on safe levels. The risks to health are more likely to be indirect; if decarbonising energy is also linked to excessive price rises, it could cause a situation of ‘heat or eat’. When faced with sudden changes in the cost of heating fuel (which can be exacerbated by cold events), households have to make choices about what they spend their income on(22). The effect is that households eat less and possible less nutritious foods, which will have knock on effects on health, particularly children(23). It is essential that alongside plans to decarbonise the energy supply that policies are put in place that can mitigate the burden placed on vulnerable households, such as energy efficiency programmes. Decarbonising the power sector can have major benefits to health by reducing outdoor levels of air pollution, which in turn will reduce both the outdoor and indoor exposure(21).

On balance, if properly implemented, actions to mitigate climate change in the UK through energy efficiency in housing and decarbonising the power supply can have benefits to health by reducing exposure to cold and reducing exposure to outdoor air pollutants(24). It will also offer indirect health benefits by providing more resilience during extreme cold and heat events(25).

Further, while there may be health risks around the actions we need to take to mitigate climate change, the potential negative impacts of not taking action and facing the risks of an unknown future climate seem far greater.

References:

1. Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, Ball S, Bell S, Bellamy R, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet. 2009 May 16;373(9676):1693–733.

2. Johnson H, Griffiths C. Estimating excess winter mortality in England and Wales. Heal Stat Q. 2003;20:19–24.

3. Healy JD. Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 2003;57(10):784–9.

4. Wilkinson P, Pattenden S, Armstrong B, Fletcher A, Kovats RS, Mangtani P, et al. Vulnerability to winter mortality in elderly people in Britain: population based study. BMJ. 2004 Sep 18;329(7467):647.

5. Hajat S, Armstrong BG, Gouveia N, Wilkinson P. Mortality Displacement of Heat-Related Deaths: A Comparison of Delhi, São Paulo, and London. Epidemiology. 2005;16(5):613–20.

6. Wilkinson P, Landon M, Armstrong B, Stevenson S, McKee M, Fletcher T. Cold comfort: the social and environmental determinants of excess winter death in England, 1986-1996. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. York, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2001.

7. Jackson G, Thornley S, Woolston J, Papa D, Bernacchi A, Moore T. Reduced acute hospitalisation with the healthy housing programme. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011 Jul 1;65(7):588–93.

8. HM Government. The Carbon Plan: Delivering our low carbon future. London, UK: DECC; 2011.

9. DECC. The Energy Efficiency Strategy: The energy efficiency opportunity in the UK – Strategy and Annexes. London, UK: Department of Energy and Climate Change; 2012 Jun p. 109.

10. BIS. Low Carbon Construction. London, UK: Department for Business Innovation and Skills; 2010.

11. Oreszczyn T, Hong SH, Ridley I, Wilkinson P. Determinants of winter indoor temperatures in low income households in England. Energy Build. 2006 Mar;38(3):245–52.

12. Hong SH, Gilbertson J, Oreszczyn T, Green G, Ridley I. A field study of thermal comfort in low-income dwellings in England before and after energy efficient refurbishment. Build Environ. 2009 Jun;44(6):1228–36.

13. Critchley R, Gilbertson J, Grimsley M, Green G. Living in cold homes after heating improvements: Evidence from Warm-Front, England’s Home Energy Efficiency Scheme. Appl Energy. 2007 Feb;84(2):147–58.

14. Oreszczyn T, Ridley I, Hong SH, Wilkinson P. Mould and winter indoor relative humidity in low income households in England. Indoor built Environ. 2006;15(2):125–35.

15. Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan;2:CD008657.

16. Bone a., Murray V, Myers I, Dengel a., Crump D. Will drivers for home energy efficiency harm occupant health? Perspect Public Health. 2010 May 28;130(5):233–8.

17. Milner J, Shrubsole C, Das P, Jones B, Hamilton IG, Chalabi Z, et al. Unintended consequences of climate change mitigation for radon-related lung cancer. Proceedings of the 2013 Annual UK Review Meeting on Outdoor and Indoor Air Pollution Research, 23-24 April. Cranfield, UK: Institute of Environment and Health; 2013.

18. Shrubsole C, Macmillan A, Davies M, May N. 100 unintended consequences of policies to improve the energy efficiency of the UK housing stock. Indoor Built Environ. 2014;In Press(Special Issue).

19. Staddon PL, Montgomery HE, Depledge MH. Climate warming will not decrease winter mortality. Nat Clim Chang. Nature Publishing Group; 2014 Feb 23;advance on.

20. Markandya A, Wilkinson P. Electricity generation and health. Lancet. 2007 Sep;370(9591):979–90.

21. Markandya A, Armstrong BG, Hales S, Chiabai A, Criqui P, Mima S, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: low-carbon electricity generation. Lancet. 2009;374(9706):2006–15.

22. O’neill T, Jinks C, Squire A. “Heating Is More Important Than Food.”J Hous Elderly. Routledge; 2006 Dec 18;20(3):95–108.

23. Bhattacharya J, DeLeire T, Haider S, Currie J. Heat or Eat? Cold-Weather Shocks and Nutrition in Poor American Families. Am J Public Health. American Public Health Association; 2003 Jul 10;93(7):1149–54.

24. Wilkinson P, Smith KR, Davies M, Adair H, Armstrong BG, Barrett M, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: household energy. Lancet. Elsevier; 2009;374(9705):1917–29.

25. Wilkinson P, Smith KR, Beevers S, Tonne C, Oreszczyn T. Energy, energy efficiency, and the built environment. Lancet. Elsevier; 2007 Sep 29;370(9593):1175–87.

Close

Close