Blog by Mitakshi Sirsi, MSc Environmental Design and Engineering at the Bartlett School of Graduate Studies

Urbanization has spread rapidly in the past decades and Humanity has chosen it as the path it intends to take in the coming future. Cities are undoubtedly going to be a defining factor in the way we progress into a new era. Hopefully, In a utopian world – aan era of climate-change mitigation and adaptation and clean energy.; A more sensitive, equitable, rational and well, nicer era!

The first impression one might have when considering cities, developing countries and climate change is, “it’s complicated!” It might just be! I had a similar reaction when I asked myself that very question as a rookie architect trying to build “green buildings” in a developing country. I hardly imagined that the question would throw up so many aspects to explore, so much hope and so much despair all at the same time; because the climate-change story is not just a story of numbers and statistics or problems and solutions – it is a story of people and the planet, of humanity, and that is probably the most complicated bit of it all.

Through this short article I hope to outline some of the major ideas I have come across with respect to climate change, cities and the promising, developing, global south to give the reader a brief glimpse into the current complex situation the way I see it.

Why do we need to talk about cities in the developing world?

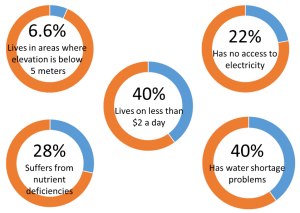

Urban areas currently host more than half the world’s population,population; cities allegedly use up 67% of the world’s resources, produce 75% of the world’s carbon emissions but only take up about 3% of the world’s land mass. The UN estimates that people living in cities will go up from 3.2 billion to about 5 billion by 2030 and up to 7 billion in 2050. This roughly translates to about 7 out of every 10 people on the planet living in an urban area by 2050. Currently, most of this growth is in the developing world (so around 5 of these 7 people are going to be in a developing country), three-fourths 3/4th of the largest cities in the world are now in the global south and the between 2000-10 the developing world accounted for more than 90% of the growth in cities in the past two decades!

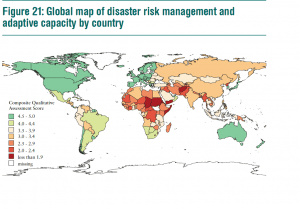

Data varies , so does its interpretation, but whatever these varying numbers are, they indicate a clear trend-shift which requires a good bit of attention. It is important to understand that some of the challenges that these cities and countries face are likely to be very different from the post-industrial revolution cities. Needless to say, developed countries currently face their own set of problems; there may be a lot to learn from their experience and by not repeating past mistakes.

Adverse impacts of climate change are already being recorded in different parts of the world – in the past decade, floods and sea level rise have affected up to 40% landmass of cities like Dhaka, these extreme events not only have direct immediate impacts like loss of life, and property, livelihoods but also indirect, long- term impacts requiring us to focus on making cities more resilient to uncertainties like loss of fertile land and impact on food security.

Climate-change may be taking over the conversation space on your lunch break, but isn’t it scary to imagine that it is taking over homes, agricultural lands and lives in some other parts of the world? (In the past few months, it has been doing that just a few kilometres south of London too!)

What does our future look like?

We don’t really know.

Not that I’m speaking from any personal experience of crystal gazing, but ‘uncertain’ is the term everyone is using. What climate scientists say they know for sure is that global mean temperatures will increase, more ice will melt, sea levels will rise, oceans will acidify more and that reaching a 2 degree C shift may push us to a tipping point – but what that means in exact terms is variable. and may be different across the planet. Developing countries will face more water stress, rain-fed agriculture will suffer, floods and droughts might increase, and monsoons might fail or get more intense. The IPCC (2007) notes that “Taken as a whole, the range of published evidence indicates that the net damage costs of climate change are likely to be significant and to increase over time.”

However, even these extreme predictions have been criticised by many as conservative. Al while some argue that an alarmist view might accelerate necessary measures to mitigate. Societies and ecosystems are likely to be impacted in different ways depending on where you are on the planet. though iImpact on societies and ecosystems may be different depending on your location, developing countries may face more water stress, rain-fed agriculture will suffer, floods and droughts might increase, and monsoons might fail or get more intense. GgGlobally. It means an it means an increase in the likelihood of impacts on food security and health, possible conflict, more migration from stressed areas, intensification if the energy crisis and more extreme weather events.

The general consensus is that (poor) people in cities of poor countries will face the brunt of anthropogenic emissions related climate- change (incidentally, developed countries are largely responsible for GHG emissions till nowhistorical data proves that these emissions are by the developed countries), and the global inequity related to energy use and energy poverty gets highlighted in this context. Some of these complicated and difficult issues are what global alliances and meets like the COP 19 and previous UNFCCC protocols are currently trying to address.

What are the core issues developing cities face?

Environment related challenges: Rapid growth increases stress on the physical structures of our cities – polluted air and water, degradation of ecosystems, overcrowding leading to health problems and such. It also puts more stress on surrounding natural systems as cities become more resource intensive when they grow. Current urban economic systems tend to be unsustainable and in the race for quick economic development, holistic sustainability goals get left behind. Some of these are evident in recent air quality reports in megacities like Delhi “Children in Delhi have lungs of chain-smokers!”

Economic and Social inequity, Governance and management: Urbanization has always brought with it a range of possibilities – cities are thriving, resilient places with ample opportunity, jobs, education, education for women, social upliftment and escape from degraded agricultural land and rural unemployment. They have been centres of migration for these very reasons but these opportunities and upliftment also brings with it them poverty, hunger and disease. Large populations in developing megacities live and work informally, about 40% of the population of cities like Bangkok and Manila live in slums. These places may be centres of economic and social activities despite the poverty, but basic infrastructure suffers, leaving them more vulnerable to extreme events. Governance and planning also play a very important role.Governance is difficult and civil systems in developing countries are not yet equipped to manage these issues.

Energy, Emissions, buildings and urban climate issues: Cities require lots of energy in different forms. Most cities still use fossil based energy and this can increase emissions greatly,. it also highlights direct impacts on energy security. The building sector is linked mainly to energy use, carbon emissions and waste, (global: 40% of energy consumption, 12% fresh water & 40% waste volume) and these numbers sometimes make us forget that buildings essentially support city activities, they are the metaphorical “core organs” of cities and are fundamental to the functioning of any city. Housing deficits, construction technology knowledge, infrastructure and “prosperity” are all a part of this equation.

The IEA estimates that Asia’s share of global energy consumption is expected to increase three times by 2030. These increases may be largely attributed to cities, and a big large chunk of that to buildings. Urban climate issues like overheating (due to the heat Island effect) can have adverse impacts on energy use,use; especially in the tropics where cooling needs are already high (anthropogenic heat added to this equation in buildings just makes it worse). Density in cities may not allow the full use of renewables and reliance on fossil fuels may be inevitable.

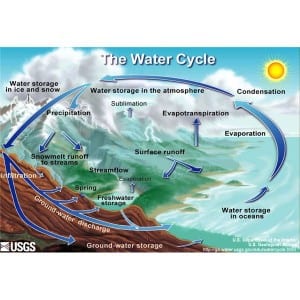

Water and Waste: Access to clean water, sanitation facilities and sustainable physical infrastructure for these systems is one of the biggest challenges cities face. The already overloaded and sometimes crude existing systems are not equipped to serve such rapid growth and may often fail, resulting in health outbursts and other social and economic problems.

Who is dealing with the problems and how?

Despite all these problems cities are growing and are very important and thriving economic, cultural and social centres. With climate-change and energy security bagging important places in the list of current global challenges, many steps are being taken to manage these complicated issues. Agencies such as The World Bank, ADB ACCCRN and UN have several programs that address these problemsissues, research bodies and universities (like our very own UCL!) are creating knowledge in the field and industry pioneers are testing solutions. Although investment in climate proofing and resilience building is currently low, the sector is growing, partly for the sake of the environment and largely because it is starting to make economic sense. Policy is changing too, local groups are starting to address problems from grassroots and governments through top-down approaches. This is especially important because both problems and solutions are contextual, but also need to be brought together as a whole.

Having said this, the situation is far from ideal. As a community of people addressing this large scale global challenge, we seem stuck between a future we cannot predict and a past we seem to keep ignoring while we jump from managing one crisis to the next, reacting and not necessarily pro-acting. Knowledge in the field is vast and we come up with new, innovative ideas often. Experts and groups from multidisciplinary backgrounds are not coming together to look for more answers. So iIt seems that the time has come for us to put more effort into applying this knowledge to the real issues through more policy, governance and management. Do we have an answer? Are we doing what we can? I don’t know. But then again, I don’t, but mmaybe it is not just about doing what we can, but about soldiering on and doing what we must.

Notes and Further reading:

The terms Global South and developing countries and developing world have been used interchangeably; population and other data are from UN and WHO sources.

This article is a short collection of what I have learnt in my exploration of this complex topic, I would be very happy to learn more, please email me at mitakshi.sirsi.13@ucl.ac.uk with any comments or observations you may have. Conversation is always welcome!

• A Guide to Climate Change Adaptation in Cities: Web toolkit, World Bank http://www-esd.worldbank.org/citiesccadaptation/index.html

• Climate Change Resilience, Rockefeller Foundation http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/our-work/current-work/climate-change-resilience/asian-cities-climate-change-resilience

• “Children in Delhi have lungs of chain-smokers!” http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/pollution-in-delhi-cng-children-in-delhi/1/344904.html

• UCL and Future Proofing Cities http://www.futureproofingcities.com/

• Some interesting scenarios people have come up with – Future Timelines – http://www.futuretimeline.net/21stcentury/2050-2059.htm

Travelling through India for fieldwork related to my projects has allowed me to test my knowledge firsthand. I have found landowners and workers, tied to income and livelihood from land and monsoon to be extremely vulnerable to current climate variability and future climate change. Household concerns in these areas can often be linked with unsustainable use of land, water and biomass resources. The three issues are inter-linked in a typical ‘village ecosystem’, and a failure in one aspect will lead to complex knock-on effects on the others. For example, wind and water led soil erosion elicits land degradation, low water availability and low and non-sustainable biomass (food) production. A common practice I came upon in areas of low water availability was a fixation with excessive digging of bore-wells to source water for irrigation, which was leading to further ground-water decline. Somini Sengupta, who wrote an article on India’s groundwater woes for the New York Times, best captures this phenomenon. She writes, ‘with India’s population soaring past 1 billion and with a driving need to boost agricultural production Indians are tapping their groundwater faster than nature can replenish it, so fast that they are hitting deposits formed at the time of the dinosaurs’. Similar headlines have emerged in Africa, where issues of land access mean a groundwater crisis looms despite recent discoveries of vast aquifers.

Travelling through India for fieldwork related to my projects has allowed me to test my knowledge firsthand. I have found landowners and workers, tied to income and livelihood from land and monsoon to be extremely vulnerable to current climate variability and future climate change. Household concerns in these areas can often be linked with unsustainable use of land, water and biomass resources. The three issues are inter-linked in a typical ‘village ecosystem’, and a failure in one aspect will lead to complex knock-on effects on the others. For example, wind and water led soil erosion elicits land degradation, low water availability and low and non-sustainable biomass (food) production. A common practice I came upon in areas of low water availability was a fixation with excessive digging of bore-wells to source water for irrigation, which was leading to further ground-water decline. Somini Sengupta, who wrote an article on India’s groundwater woes for the New York Times, best captures this phenomenon. She writes, ‘with India’s population soaring past 1 billion and with a driving need to boost agricultural production Indians are tapping their groundwater faster than nature can replenish it, so fast that they are hitting deposits formed at the time of the dinosaurs’. Similar headlines have emerged in Africa, where issues of land access mean a groundwater crisis looms despite recent discoveries of vast aquifers. Close

Close