More detail needed on what’s next for education policy

By Blog Editor, on 25 June 2024

The manifestos are out and the general election is looming. We at CEPEO, as the name suggests, are particularly interested in education policy and equalising opportunities. So, what did the manifestos actually tell us about potential plans in these areas? We focus here on plans set out by the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties.

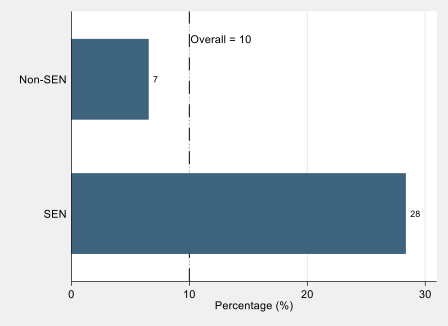

While the details differed, there were some agreed areas of importance across the parties: the need to recruit, train and retain high quality teachers; to do more to support children with special educational needs; and to incentivise more adult learning. These issues would probably appear quite high up most lists of pressing issues likely to be facing the Department for Education over the next few years.

There was also an emphasis on support for disadvantaged students. The Conservatives highlighted £3bn of spending via the pupil premium – helpful, of course, but only so high because of the very large proportion of pupils eligible now – 25% as of January 2024. Some of this rise is driven by transitional arrangements for Universal Credit, but I’m sure we could all agree that it would be better for far fewer children to be experiencing low family income, even temporarily.

The Liberal Democrats promised to go further on this front by tripling the early years premium to bring it closer to the amount allocated to school children – and extending the pupil premium it to those aged 16-18 as well – both very welcome ambitions. There were no specific details on this issue in the Labour manifesto, but one of their five missions is to break down barriers to opportunity, so there may be more specific announcements to come if they are the ones in office come 5th July.

There were also some clear omissions though. There was very little detail on what might be done to shore up HE funding. Labour and the Liberal Democrats were clear that ‘something’ should be done, but unclear what that would look like. Certainly no-one was brave enough to say that tuition fees might need to go up substantially. We can probably expect another independent review in the coming months to spell out the unappealing choices. The Lib Dems did commit to reintroducing maintenance grants, though, while the Conservatives re-emphasised their plan to close down “poor quality” degrees, which of course are challenging to identify and may disproportionately affect those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, as we have discussed previously.

In contrast to the strong focus on the importance of high-quality staff for schools, there was also very little in the way of detail on a potential workforce strategy to help deliver the extended early education entitlements to children in working families from 9 months, which both the Conservatives and Labour have committed to delivering. The Conservatives are presumably relying on the market to deliver the places (and staff), incentivised by the higher funding rates they have committed to over the coming years. Labour are planning to re-use freed-up space in primary schools to deliver more places, but have not provided any specific details of their plans for the workforce.

While it is possible that providers will use some of the higher government funding to pay staff more, the market does not provide a strong incentive to invest in high quality staff – or in quality more generally. It is challenging for parents to identify setting quality (beyond Ofsted ratings) and many also weigh other considerations – such as availability and convenience – more highly when choosing a place for their child, suggesting that more will need to be done if we are serious about delivering high quality early education.

There is also a lot more that could be done to distribute this funding more equitably, as I spell out in this companion piece. And, of course, it would have been great to see consideration of some of our more ambitious policy priorities to equalise opportunities, including reforming school admissions, introducing a post-qualification admissions system and greater commitment to funding for further education (although credit to the Liberal Democrats for making an explicit commitment on this).

Of the three, the Liberal Democrat manifesto was the most ambitious in terms of the number and scope of specific policy ideas to equalise opportunities – but it certainly wasn’t radical. We must therefore hope that the next government is going to over-deliver on its manifesto commitments. For, as my colleagues so eloquently put it in a recent blog post, there can be no economic growth without education and skills. Ensuring that the benefits of this growth are distributed equitably starts with the education system. We here at CEPEO therefore hope that bolder action to equalise opportunities in education is just around the corner, whichever party is in power next month.

Close

Close