UCL IHE TechSharing Seminar Series – Global Digital Health

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 18 February 2020

The UCL TechSharing Seminar Series aims to foster knowledge exchange between academics, clinicians, policy makers and industry professionals working at the intersection of healthcare and digital technologies. The first seminar in the 2020 iteration of the series (supported by the UCL Institute of Healthcare Engineering) took place on January 16th and was hosted in collaboration with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). The seminar focused on healthcare delivery (e.g. point of care diagnostics, clinical decision-making, remote data collection) via smartphone apps and related technologies in low resource settings. Four speakers provided fascinating insights into the opportunities and challenges of conducting digital health research in a global context. A number of important lessons were highlighted across the presentations, summarised below.

The next seminar in the series will focus on ethics in multidisciplinary digital health collaborations (date TBD).

***

In his keynote presentation, Dr Andrew Bastawrous talked about his journey to setting up PeekVision – an organisation which uses smartphone technology and related software to support eye testing and care in remote locations. While cost-effective solutions are available (e.g. glasses, cataract surgery), accessibility issues mean that millions of people in need of eye care are not catered for. Dr Bastawrous drew on his personal and clinical experiences to demonstrate how a technology like PeekVision can help meet such healthcare needs. He talked about how the ideas behind the project evolved, starting from early, logistically cumbersome population-based research (e.g. screening programmes) which required the transport of costly NHS diagnostic equipment to remote and poorly connected areas in sub-Saharan Africa, to projects involving teacher-led and smartphone-enabled eye tests. Peek Vision’s story highlights the importance of adapting to the local context, engaging a wide range of community members (e.g. parents, headmasters, teachers) and seizing unexpected opportunities – in communities where access to running water, high quality roads, or electricity is limited, the majority of people might still have access to mobile phones.

Lessons learnt: (1) without diligent and transparent data collection and analysis at each stage of the project, it would not have had the same impact, as the data collected allowed the project team to identify areas for improvement; (2) simple solutions are often preferable to complex ones, such as using a piece of string (as opposed to sophisticated algorithms) to measure the right distance for conducting smartphone-enabled eye tests.

“We are now connected in a way that we’ve never been, we have better computational power than ever before, and this can help to address unmet needs in even the most remote communities.”

“We are now connected in a way that we’ve never been, we have better computational power than ever before, and this can help to address unmet needs in even the most remote communities.”

***

The second talk was delivered by Dr Cathy Holloway who shared the story behind the UCL Global Disability Innovation Hub. The Hub brings together international organisations, including the World Health Organisation, and local partners in India and Africa, to support a range of initiatives focused on improving the lives of people living with disabilities. For example, the Hub is involved in the building and testing of innovative assistive technologies such as prosthetics in low resource settings. Dr Holloway shared insights into both practical and ethical challenges facing researchers working in the field of assistive technologies. First, many countries have other health priorities, such as poorly controlled malaria or HIV, and struggle to fund core healthcare services, such as teaching and nursing. In this context, initiatives that immediately save lives are more likely to be adopted and supported by governments and charitable organisations. Second, assistive technologies can sometimes increase disability and dependence. For example, providing people with smartphones may require that the majority of features/functionalities are first removed to reduce costs, or create dependence on carers or other intermediaries who are tasked with accessing and handling sensitive data on the devices (e.g. bank accounts).

Lessons learnt: (1) securing sustainable funding for global disability research and related activities remains challenging; (2) project partners often possess useful domain expertise, but may have less experience working within multidisciplinary collaborations with technology developers and researchers; (3) securing ethical approval for research conducted across different countries can take much longer than anticipated; (4) the success of global health projects relies on trust and regular communication with stakeholders and partners – it is therefore key to budget for site visits to strengthen links between project partners and better understand the context where the work is taking place.

Dr Michelle Heys from the UCL Institute of Child Health presented on NeoTree, a not-for-profit and open source smartphone app to support clinical decision-making in neonatal care. In the absence of specialist paediatricians in many low resource settings, target end-users include nurses and healthcare assistants who oversee the day-to-day care of the newborns. NeoTree was developed in line with the Medical Research Council’s framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions and is grounded in co-design and participatory research with relevant stakeholders, including nurses and doctors. NeoTree also aims to improve the ways in which data are collected and managed in neonatal units. The NeoTree platform is currently used for the admission and discharge of babies across hospitals in Malawi and Zimbabwe and offers diagnostic support for nursing staff. Dr Heys discussed the potential for the platform to deliver training and behaviour change interventions for healthcare workers in the near future.

Lessons learnt: (1) technology can be an important part of the solution, but capacity building and education of healthcare workers remain necessary to improve health outcomes; (2) building and implementing algorithms to support clinical decision making in the real world remains a challenge – there are still grey areas that are difficult for algorithms to replace, which are normally addressed by humans drawing on their accumulated experience and clinical judgement.

The final talk was delivered by Dr Chrissy Roberts (LSHTM) and focused on technology platforms that enable high quality data collection ‘for the masses’, i.e. for anyone without specialist IT skills. Dr Roberts has set up and is now curating the Open Data Research Kits. His work has spanned the establishment of secure servers at LSHTM which support data collection and management for global partners, through to establishing a tablet-rental scheme for data capture, training for field workers, and curating online learning resources. Currently, the Open Data Research Kits are used by researchers globally, including the recent Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Dr Robert’s work is grounded in the need for a system that can be used to reliably and securely collect high quality data in global contexts, particularly in resource-poor and challenging environments (including extreme weather conditions!). Dr Roberts outlined how the Open Data Research Kits help to meet core requirements that he and other global health researchers have for a data capturing system: being able to work both off- and online; encryption, zero cost, remote/automated monitoring, instant data sharing, media assisted surveys (to capture images, barcodes, audio and video), third party app integration and sustainability.

Lessons learnt: (1) with the right tools (many are open access and affordable), anyone can collect high quality data in low resource settings; (2) community-based technologies and software can be more sustainable and up-to-date than commercial software thanks to the existence of a wide network of users and contributors; (3) demystification through training can help to increase uptake of new technologies among those who remain skeptical (e.g. teaching MSc students and field workers how to use new software can help promote such technologies to senior team members).

Biography

Dr Aleksandra Herbec is a mixed-methods researcher specialising in tobacco control, behavioural science and digital health. She is based at the UCL Centre for Behaviour Change where she investigates ways to improve antibiotic stewardship and infection prevention and control and leads evaluations of smartphone-based aids for medication adherence and smoking cessation.

Dr Nikki Newhouse is an interdisciplinary qualitative researcher whose primary research interest is in human-computer interaction, in particular the development and evaluation of complex digital interventions to support physical and psychological wellbeing across the lifespan. She is based at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford.

Dr Olga Perski is an interdisciplinary researcher working at the intersection of behavioural science and technology. She is a Research Associate in the UCL Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group, where her work is focused on the development and evaluation of digital interventions for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction.

How to design a health app for users who are not motivated to change? Insights from the Precious app

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 4 February 2020

The Precious app was designed to support healthy living: a physically active lifestyle, balanced nutrition and stress management. In a study published in JMIR mHealth and uHealth, we describe how we designed the Precious physical activity app features for users whose needs are not met by traditional activity tracker apps.

Most available physical activity apps provide factual information on performance with numbers and graphs, and they can be a great resource for those who are already active and who want to monitor their progress. Millions of users regularly log their running and cycling routes using smartphone sensors or wearables that connect with apps such as Strava. However, not everyone enjoys physical activity, and not everyone finds numerical data meaningful. For some, constantly failing to reach the goals set by exercise apps (such as 10,000 steps a day) can be a major stressor. Although good health is the goal for many, sometimes people only feel motivated to take care of themselves after facing a serious health concern.

Physical activity is good for our physical and mental wellbeing and those with the lowest levels of activity would benefit most from adopting some exercise in their life. Building on psychological research on motivation and self-regulation, we came up with two ways of catering to users with low motivation for activity in the Precious app: reflective and spontaneous support.

Reflective support through Motivational Interviewing

Most of us know about the health benefits of a physically active lifestyle. Thus, there is little need to remind people what they should do. Somewhat surprisingly, psychological research shows that a much more effective strategy is to help people think what they want to do [1].

In the Precious app, we used Motivational Interviewing techniques [1] to support people who struggle to fit physical activity into their daily lives. One of the key techniques is to ask questions that help the users reflect on how healthy behaviours could help them reach goals that are meaningful for them. When users start to express their desire to change or the reasons to become active, they are eliciting change talk. This is a central concept in Motivational Interviewing: helping people to put into words how behavioural changes can help them live a life that corresponds to their values.

In the Precious app, users are first guided to think about what really matters to them. This does not need to be health related: the basic psychological needs for human motivation are connectedness to others, experiencing competence in their actions, and having the freedom to pursue personally meaningful goals. [2] This thinking is based on Self-Determination Theory which has repeatedly shown that individuals engage in behaviours when these are in line with their values and identity [3].

Once the users have reflected on their life values, they are encouraged to think about if physical activity could help them achieve those things. Among the test users of the Precious app, physical activity was typically perceived as helpful, as physical exercise can, for instance, increase energy levels and help to manage stress. Whether people prioritise their family, their health or their career, improved physical and mental well-being is an asset.

The next step is to help users think about practical ways in which physical activity can take them closer to their life goals. For instance, if a user has indicated that feeling connected to others is most important to them, they can choose activities that can be done together with family or friends. The aim of the Motivational Interviewing tools is not simply to engage users with the app, but to engage them in the behaviour change process: to actively consider reasons for change and to take practical steps toward change (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshots from the Precious app.

Spontaneous support through gamification

Behaviour change does not necessarily require active reflection but can tap into the motivational effect of intrinsic pleasure. Gamification is the use of game elements for making a task more engaging and entertaining. For instance, the Conquer the city feature in the Precious app was designed to increase walking by making users conquer and defend areas in the area they live in by walking around buildings or blocks. Game elements can change users’ focus from feeling like they are ‘just walking’ to the task at hand and make people spontaneously active without even realising. Similar ideas have gained success in games like Ingress, Pokemon Go or Zombies, run!, where augmented reality elements lure players to walk further or run faster. An activity that is not necessarily fascinating in itself can become more enjoyable with augmented reality elements. People who do not find physical activity pleasurable may enjoy gamified visualisations, goals and challenges that they only achieve while being active.

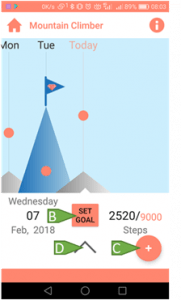

The ‘Mountain climber’ tool provides a visual interpretation of activity and goal achievement

Following these principles, the evidence-based self-regulatory behaviour change techniques [4] in the Precious app were built into a Mountain climber tool (see Figure 2). It depicts daily activity as a mountain and shows a little flag on top of the mountain on days when users achieved their personal step goal. This self-regulation tool was designed so that people could monitor their daily steps even without looking at numbers. They can see if their mountain panorama is growing over time and learn what type of activities lead to the highest mountains.

Figure 2. The ‘Mountain climber’ tool.

To help users estimate more accurately how much activity they have done every day, the planning tool in the Precious app indicates how many steps each activity corresponds to. Users can fill in the minutes they spent swimming, lifting weights, etc., and the app will display how many steps these activities correspond to using MET values. All activities contribute to the daily step count and are visualised as one mountain, providing an easy day-to-day comparison.

The Precious app tries to convey that people do not need to become athletes in order to be physically active. Vacuuming the house or helping a friend to move can be the dose of daily physical activity – a realisation that can be a relief for someone with a busy schedule! The main thing is to make physical activity more enjoyable, or to at least see how it can help achieve things that matter most.

Questions

- The Precious app helped users elicit change talk in the interview situation. Will the effect carry on in a natural environment, over time?

- Health apps can be tailored to meet the needs of people with low technology literacy and little motivation for behaviour change, but how do we reach these potential users?

Read more:

Nurmi J, Knittle K, Ginchev T, Khattak F, Helf C, Zwickl P, Castellano-Tejedor C, Lusilla-Palacios P, Costa-Requena J, Ravaja N, Haukkala A. (2020). Engaging Users in the Behavior Change Process With Digitalized Motivational Interviewing and Gamification: Development and Feasibility Testing of the Precious App. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. DOI: 10.2196/12884 URL: https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/1/e12884/

Johanna Nurmi is finalising her PhD in Social Psychology at the University of Helsinki and working as a visiting researcher at the Behavioural Science Group, University of Cambridge. She studies how motivational techniques and related cognitions affect individuals’ daily physical activity. Johanna’s research has been supported by the University of Helsinki; the Yrjö Jahnsson foundation; and the KAUTE foundation.

The Precious project was funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement number 611366, and built in multidisciplinary collaborations with partners across Europe.

Find Johanna here:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/johanna-n8714aa4/

The promise of public health app portals (versus commercial app stores) in promoting the adoption of digital behaviour change aids

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 11 December 2019

By Dr Olga Perski & Dorothy Szinay

To estimate the likely public health impact of digital behaviour change aids, we need to consider both their effectiveness and how far they are adopted within the target population. Although digital aids for smoking cessation, alcohol reduction, physical activity and dietary improvement have small, positive effects on behaviour (in comparison with no or minimal support), they have the potential to reach a much larger number of people than conventional, face-to-face treatment. For example, digital aids are easy to access for those who live too remotely to access available face-to-face support or who feel anxious about the prospect of talking to a healthcare professional about their health. Previous studies have described the characteristics of users (e.g. smokers, drinkers) who sign up to take part in controlled trials of digital aids or who self-select to download a particular app for smoking cessation or alcohol reduction. However, we currently know little about the reach of digital aids in the general population, which makes it difficult to judge whether they are in fact delivering on their promise of wide reach.

Observed adoption rates in the general population of smokers and drinkers in England

In a recent study published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, we assessed adoption rates and characteristics of those adopting digital aids for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction in a nationally representative sample in England. A total of 3,655 smokers and 2,998 high-risk drinkers (defined as a score of >4 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption; AUDIT-C) who had made a past-year quit/reduction attempt were surveyed as part of the Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Studies between 2015 and 2018. They were asked if they had used a digital aid (e.g. website, smartphone app) in a recent quit/reduction attempt. In weighted analyses (used to match the sample to the proportions of the English population on age, social grade, etc.), we found that 2.7% of smokers and 3.6% of high-risk drinkers had used a digital aid in a recent quit/reduction attempt. Hence, our findings suggest that digital aids for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction are not yet reaching a large proportion of the target population in England. Another key finding was that none of the smoking or sociodemographic variables assessed were significantly associated with the uptake of digital aids in smokers. In high-risk drinkers, however, those who were highly motivated to reduce their drinking and had a higher AUDIT score had greater odds of adoption. This means that we may specifically need to focus promotion efforts on those with lower motivation to change going forwards.

Why are adoption rates so low?

These low adoption rates could be due to the lack of public or healthcare professional awareness of, or confidence in using/recommending the use of, digital aids. It should, however, be noted that public-facing campaigns in England (e.g. Stoptober, Dry January, One You) have promoted the use of smartphone apps for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction for several years. As the Smoking and Alcohol Toolkit Studies don’t currently include measures of awareness of available aids, we weren’t able to assess if the low adoption rates are indeed attributable to low awareness. Recently, regulatory frameworks for digital aids have been developed in the UK, with related resources (e.g. the NHS Apps Library) specifically designed to help healthcare professionals and patients navigate the host of available apps. It’s hence possible that increased awareness of and confidence to use/recommend evidence-based apps via curated, public health app portals among healthcare professionals and patients may help to speed up the adoption process.

The potential for public health app portals

As part of her PhD project, funded by Public Health England, Dorothy is in the process of developing and evaluating a web-based intervention, delivered via a public health app portal, to increase the adoption of health and wellbeing apps in England. Her ongoing qualitative research aims to explore potential users’ views on available public health app portals (e.g. One You Apps), with a view to identifying areas for improvement. Early findings suggest that the majority of participants weren’t aware of existing portals, although a few had heard of some of the apps listed through social media. All participants recognised the benefit of the portals and expressed their trust in and respect towards the National Health Service/Public Health England. However, the manner in which the apps are currently presented on the portals did not meet users’ expectations and led them to continue their searches in commercial app stores. Participants thought that the apps are not as clearly presented on current health portals (as compared with commercial app stores), and a few users did not manage to find an app for their key behaviour of interest. It should be noted that, at the time of the interviews, no smoking cessation app was listed on the NHS Apps Library, and only one was listed on the One You Apps portal. The next step is to use these findings to inform the development of an intervention to promote the adoption of health and wellbeing apps, delivered by a real or sham public health app portal.

Questions

- What is the role of national health organisations (e.g. the National Health Service, Public Health England) in promoting evidence-based digital behaviour change aids?

- What is the best strategy for redirecting people interested in digital behaviour change aids from commercial app stores to public health app portals?

Bios

Dr Olga Perski is a Research Associate in the UCL Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group. Her research focuses on the development and evaluation of digital aids for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction.

Dorothy Szinay is a PhD candidate at the University of East Anglia. Her research focuses on the development and evaluation of web-based interventions to increase the uptake of and engagement with health and wellbeing smartphone apps.

Understanding intervention effectiveness using novel techniques: Report from EHPS 2019 Symposium

By Emma Norris, on 9 October 2019

By Emma Norris, Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters, Neža Javornik, Marta M. Marques, Keegan Knittle, Alexandra Dima

The European Health Psychology Society (EHPS) had its 2019 conference from 4-7th September in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The packed programme featured a wide range of research across health psychology, including digital interventions, theoretical and methodological advances, chronic illness, preventive health and much more.

This extended blog summarises a symposium in showcasing novel techniques and tools for intervention specification entitled ‘Understanding intervention effectiveness: analysing potential for change, improving intervention reporting, and using machine-readable decision justification’. The symposium aimed to address an urgent question in health psychology: How can we design more effective interventions? The 5 presentations presented practical tools to support researchers in our united mission to increase our understanding of intervention effectiveness and better support population health. We present a summary of each presentation, followed by some concluding thoughts and questions from the symposium’s discussant Dr Alexandra Dima.

You can find the slides for the symposium here: https://osf.io/hvkaz/

Potential for change (PΔ): New metrics for tailoring and predicting response to behaviour change interventions – Keegan Knittle, University of Helsinki

A novel integrative construct, potential for change (PΔ), accounts for ceiling/floor effects to predict an individual’s likelihood of response to an intervention. Using baseline data from a randomised controlled trial testing the ‘Let’s Move It’ physical activity promotion intervention, the team calculated determinant-level PΔ scores for 12 named theoretical determinants in the intervention. They then calculated ‘PΔ-global’, the mean of the 12 PΔ-determinant scores, weighted by each determinant’s association with MVPA at baseline. In this way, PΔ could also be seen as a measure of the extent to which a theory underlying an intervention matches with an individual intervention recipient. Among intervention recipients, PΔ-global followed a normal distribution and was significantly related to increases in accelerometer-measured MVPA (r=.269; p<.001) and self-reported days per week with at least 30 minutes of MVPA (r=.175; p=.001): the intervention’s primary outcomes. Hence using data from the Let’s Move It study, PΔ-global accounted for floor/ceiling effects and predicted response to a theory-based behaviour change intervention. Possible future uses of PΔ include applying it to time-series data of individual determinants as a means to tailor intervention delivery.

– – – – – –

Reporting the characteristics of treatment-as-usual in health behavioural trials – Neža Javornik, University of Aberdeen

Treatment-as-usual (TAU), a common comparator in health behavioural trials, allows us to establish how effective an intervention is against an existing standard treatment, provided in a certain setting. Such treatment, typically delivered in person, can vary in different characteristics (e.g. who provided the treatment, how, how long it lasted for, what it contained) and influence behaviour and health outcomes between control group participants, and thus trial effect sizes, differently (e.g. de Bruin et al., 2009, 2010). For the interpretation and comparison of trials it is important that readers and systematic reviewers have a clear understanding what TAU in a particular trial consisted of. This requires some standard format for TAU reporting that the present study attempted to identify.

A narrative review was first conducted to identify the potentially important TAU characteristics, which were mapped onto existing reporting frameworks (Intervention Mapping, TIDieR and BCT Taxonomy v1). The identified characteristics were used to inform a modified Delphi expert consensus study, which aimed to identify the necessary and recommended TAU characteristics, and how detailed their reporting should be. Five stakeholder groups (N = 25) participated in anonymous online voting and discussion. The critical TAU characteristics to report at a general level of detail were primary health behaviours, active content, tailoring of active content, duration characteristics (frequency, number and length of sessions), the profession of the provider, and any major deviations from the intended TAU characteristics. Setting characteristics (location, setting, mode, rural/urban characteristics) were thought to be critical to report at the level of every clinic. This allows for understanding how TAU should be reported when describing health behavioural trials. In turn, that can lead to better understanding, interpretation and comparison of trials with a TAU comparator.

Repository: https://osf.io/n7upg/ Link to talk: https://osf.io/8erbp/

– – – – – –

Acyclic Behaviour Change Diagrams: human- and machine readable reporting of what interventions target and how – Gjalt-Jorn Ygram Peters, Open University of the Netherlands

To progress behaviour change science, research syntheses are crucial. However, they are also costly, and unfortunately, often yield relatively weak conclusions because of poor reporting. Specifically, in the context of behaviour change, the structural and causal assumptions underlying behaviour change interventions are often poorly documented, and no convenient yet comprehensive format exists for reporting such assumptions.

In this talk, Acyclic Behaviour Change Diagrams (ABCDs) were introduced. ABCDs consist of two parts. First, there is a convention that allows specifying the assumptions most central to the dynamics of behaviour change in a uniform, machine-readable manner. Second, there is a freely available tool to convert such an ABCD specification into a human-readable visualisation (the diagram), included in the open source R package ‘behaviorchange’.

ABCD specifications are tables with seven columns, where each row represents one hypothesized causal chain. Each chain consists of a behaviour change principle (BCP), for example a BCT, that leverages one or more evolutionary learning processes; the corresponding conditions for effectiveness; the practical application implementing the BCP; the sub-determinant that is targeted, such as a belief; the higher-level determinant that belief is a part of; the sub-behaviour that is predicted by that determinant; and the ultimate target behaviour. The ABCD is illustrated using an evidence-based intervention to promote hearing protection.

ABCDs conveniently make important assumptions underlying behaviour change interventions clear to editors and reviewers, but also help to retain an overview during intervention development or analysis. Simultaneously, because ABCD specifications are machine-readable, they maximize research synthesis efficiency.

Repository: https://osf.io/4ta79 Link to talk: https://osf.io/utw95/

– – – – – –

– – – – – –

Development of an ontology characterising the ‘source’ delivering behaviour change interventions – Emma Norris, University College London

Understanding who delivers interventions, or the ‘source’ of interventions, is an important consideration in understanding an intervention’s effectiveness. However this source is often poorly reported. In order to accumulate evidence across studies, it is important to use a comprehensive and consistent method for reporting intervention characteristics, including the intervention source. As part of the Human Behaviour-Change Project, this study used a structured method to develop an ontology specifying source characteristics, forming part of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology.

The current version of the Source Ontology has 196 entities covering Source’s occupational role, socio-demographics, expertise, relationship with individuals targeted by the intervention, and whether the source was paid to deliver the intervention. The Source Ontology captures key characteristics of those delivering behaviour change interventions. This is useful for replication, implementation and evidence synthesis and provides a framework for describing source when writing and reviewing evaluation reports.

Repository: https://osf.io/h4sdy/ Link to talk: https://osf.io/hg6nd/

– – – – – –

Enhancing research synthesis by documenting intervention development decisions: Examples from two behaviour change frameworks – Marta M. Marques, Trinity College Dublin & Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters, Open University of the Netherlands

To support the development of behaviour change interventions, there is a considerable amount of guidance (e.g. Intervention Mapping) on how to select behaviours, identify behavioural determinants, and select methods/techniques. When it comes to decisions about which modes of delivery are best for certain methods, and how they should be designed, there is little guidance.

While researchers make these decisions during the development of interventions, these decisions are not well documented, and as such, opportunities to learn from the justifications of those decisions are lost. An easily usable, systematic, efficient and machine-readable approach to reporting decisions and justifications of such decisions would improve this situation and enable accumulation of knowledge that at present remains largely implicit.

We introduced ‘justifier’, an R package that allows reading and organizing fragments of text that encode such decisions and justifications. By adhering to a few simple guidelines, the meeting minutes and documentation of the intervention development process become machine-readable, enabling aggregation of the decisions and their evidence base over one or multiple intervention development processes. Tools such as heat-maps can be used to visualise these patterns, quickly making salient where decisions were based on higher and lower quality evidence.

We presented examples of key decisions to justify during intervention development, using common steps in the Intervention Mapping Protocol and the Behaviour Change Wheel. Using the proposed ‘justifier’ format document the decisions and their justifications in these key domains provides greater insight in the intervention development process.

Link to talk: https://osf.io/zmb3g/

– – – – – –

Discussion: Why and when would research teams use these tools? – Alexandra Dima, Health Services and Performance Research, University Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France

Participating in a symposium that introduces 5 new tools for intervention development and reporting (or reading a blog about such symposium) may generate mixed feelings of enthusiasm and anxiety. On one hand, as it has been previously stated at the EHPS conference, it is an exciting time to be a researcher. We have the possibility to do better work and communicate better about it, so that our individual contributions can add to the common edifice of evidence. On the other hand, ‘5 new tools’ also means ‘5 new ideas’ to get one’s head around, convince others of their importance for the project, and link to specific actions or habits to integrate in the workflow. Most likely, on top of 100 more ideas one needs to master during a usual research project – assuming there is time and funding to adopt them all and work towards best practices in research, and the resulting high-quality evidence. Getting to grips with these new tools requires effort, and we should not underestimate the cost involved. On the contrary, we need to plan for it. Yet, I would argue that these 5 tools, if used adequately and at the right moment in the research process, have the potential to save costs. They do this by making it easier to ask some good but uncomfortable questions which are unavoidable in any intervention development and reporting process.

First, asking the question ‘Is there any potential for change in the target behaviour and its determinants?’ is among those key uncomfortable questions at the beginning of an intervention study. In principle one would need at least an estimation of mean and standard deviation for a sample size calculation to move on. The PΔ scores ask this question also at the individual level and thus confront us with a key conceptual puzzle: if you know that participants vary in their potential to be influenced by the intervention, should you control for it to estimate the ‘real’ effect of the intervention? PΔ scores propose a way to quantify this variation – if baseline data indicate large variations, then tailoring needs to be considered.

Second, variation is not only present in the target group, but also in the services available to them at baseline, raising another uncomfortable question: “what is already there in terms of behaviour change activities, or ‘treatment-as-usual’?”. The TAU characteristics checklist is also best considered at the beginning of intervention development. If you are planning a multi-centric study, it is even more important to ask these questions early since this is in a way a PΔ for the participating centers. Considering this checklist brings with it numerous options to consider about the intervention itself. Would it be better to add an extra service or modify the work of existing providers? Would it be beneficial or even possible to improve standardization, granularity, and reporting in current practice? Finding a balance between benefit and feasibility starts with TAU characterization.

A third uncomfortable question is: ‘who is going to do it?’ The Source Ontology gives us the common dictionary (for humans and machines alike) to report this clearly, but it’s initial value is in my opinion also as a decision tool. Once you know what 196 types of sources are available you just can’t avoid this question. No, it is not obvious that the pharmacist, or the schoolteacher, will do it. In a time of evolution towards integrated care, this question will quickly take us to the revelation that most behaviour change processes are supported by several types of people and organization, and the effect of TAU or interventions is the result of all these.

Fourth, once you are well into intervention development and start getting answers to these initial questions, another, maybe even more uncomfortable question pops up: ‘what is the logic of what we are trying to do?’. At this moment you are safer from forgetting to ask basic questions, but the dangers of lack of coherence and making choices you will regret later on is still high. ABCD props you to do the right thing: have a visual check of consistency first for yourself and then to discuss with the research team and stakeholders and make sure everyone has a chance to input at this stage and pick up any awkward or missing links. ABCD will come in handy also when reporting and for systematic reviews, if research teams will use it consistently for similar studies. But there will be little to report if ABCD, and the intervention development process it supports, are not used routinely in the development phase.

And finally, an uncomfortable and apparently innocent question with profound consequences throughout the process is: ‘what decisions should we document and how?’ The other 4 tools point to various choices which, if not taken consciously, may impact unexpectedly on intervention effectiveness and evidence quality. Justifier proposes a way to make these choices and record the decisions in a way that can be accessed automatically and tested in systematic reviews. Imagining a world in which such tools become routine practice, in time and with adequate coordination between research teams we will be able to compare these choices in terms of intervention and evidence-related outcomes. But the more tangible benefit for the individual researcher is building good habits for writing meeting minutes that can be used for feedback on the development process.

Link to Discussion talk: https://osf.io/up4t9/

– – – – – –

If you are setting up an intervention project currently, this would be a good moment to ask yourself whether you could test these tools in your project, and where. The symposium presenters have all been there and are happy to advise. For the EHPS community, and other groups interested in health behaviour change, it is time to ask ourselves how to coordinate support for research teams worldwide to have easier access and training for implementing methodological innovations in their work and, most importantly, to test their effectiveness in real research practice.

You can find the slides for the symposium here: https://osf.io/hvkaz/

Bios

Emma Norris (@EJ_Norris) is a Research Fellow on the Human Behaviour-Change Project at UCL’s Centre for Behaviour Change.

Emma Norris (@EJ_Norris) is a Research Fellow on the Human Behaviour-Change Project at UCL’s Centre for Behaviour Change.

Alexandra Dima (@a__dima) is a Senior Research Fellow in Health Sciences at Université Claude Bernard Lyon.

Alexandra Dima (@a__dima) is a Senior Research Fellow in Health Sciences at Université Claude Bernard Lyon.

Neža Javornik (@NJavornik) is a PhD student in the Health Psychology Group at the University of Aberdeen.

Neža Javornik (@NJavornik) is a PhD student in the Health Psychology Group at the University of Aberdeen.

Marta M. Marques (@marta_m_marques) is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at Trinity College Dublin, and Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London

Marta M. Marques (@marta_m_marques) is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at Trinity College Dublin, and Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London

Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters (@matherion) is an Assistant Professor in Methodology, Statistics and Health Psychology at the Open University of the Netherlands.

Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters (@matherion) is an Assistant Professor in Methodology, Statistics and Health Psychology at the Open University of the Netherlands.

Keegan Knittle (@keeganknittle) is a University Researcher at the University of Helsinki focusing on understanding people’s motivations for behaviour.

Keegan Knittle (@keeganknittle) is a University Researcher at the University of Helsinki focusing on understanding people’s motivations for behaviour.

Joining forces in research: Introducing the EHPS Special Interest Group on Digital Health and Computer-tailoring

By Emma Norris, on 1 October 2019

By Dr Laura M König – University of Konstanz, Germany & Dr Eline Suzanne Smit – University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

At this year’s 33rd Annual Conference of the European Health Psychology Society (EHPS), held in Dubrovnik, Croatia, the Special Interest Group (SIG) on Digital Health and Computer-tailoring was officially launched. This SIG aims to bring together researchers from all over Europe (and beyond) to advance research in the field of digital health promotion by stimulating networking, the exchange of ideas and joint initiatives.

Background

Interest in digital health promotion tools is growing in the general public, in policy making and in research. Recent reviews suggest that digital tools may be effective in changing a range of health behaviours, but it is also clear that there are many open questions regarding the design of digital interventions, e.g. to ensure the highest possible retention rates, their evaluation, e.g. methodological questions about ideal sampling designs, and their implementation.

To advance the field of digital health promotion, the founding of an EHPS Special Interest Group was already discussed at the EHPS conference in 2017, held in Padua (Italy). Following a survey among EHPS members (N=38), it became clear that respondents were interested in a broad range of topics including wearable devices and mobile interventions, but also online interventions more broadly and the method of computer-tailoring of digital interventions. The SIG’s mission statement therefore was formulated as “[building] a community of interested EHPS members to advance digital health and computer-tailoring research and to provide a forum to discuss new evidence, underlying mechanisms and specific components of digital health interventions that may lead to enhanced behavioural outcomes”. The founding of the SIG was announced in the European Health Psychologist in summer 2019, and it was officially launched during our first meeting on 5th September 2019 in Dubrovnik.

The launch meeting

The official launch (or lunch, as the meeting was scheduled during lunchtime) meeting was well attended: More than 30 EHPS members had already expressed their interest in advance, and even more people actually attended the meeting. It was great to see so many conference attendees interested in digital health and computer-tailoring all in one room!

After a general introduction to the SIG’s background and aims, we asked the attendees to discuss their ideas for the agenda of the SIG and future SIG activities in small groups before the ideas were fed back to all attendees and the SIG’s organising committee. In addition, we opened a call for applications to join the SIG organising committee and we are happy to say that all open positions in the committee are now filled. We are, however, always happy for people to actively contribute to the SIG, e.g. by providing input for our newsletter or by organizing a SIG related activity, so do get in touch in case you would like to contribute in any way!

Who’s on the organising committee?

Presently on the SIG’s organising committee are the following people:

Dr Eline Smit (chair)

Dr Laura König (co-chair and social media officer)

Dr Alexis Ruffault & Dr Camille Vansimaeys (communications committee)

Dr Ann DeSmet (membership officer)

Laura Maenhout & Dr Olga Perski (events committee)

Dr Katie Newby (secretary)

In addition to this core team, we have an advisory board consisting of scholars with extensive experience in digital health and computer-tailoring, as well as with running a successful SIG within the International Society for Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity (ISBNPA). The board of advisors presently consists of:

Prof Corneel Vandelanotte

Prof Hein de Vries

What’s next?

Based on the suggestions collected during the launch meeting and in the initial survey, the organising committee already decided on some future activities. To communicate with our members, we created a Twitter account (@EHPSDigiHealth) that already gained more than 150 followers since it was registered. Furthermore, we will send quarterly newsletters to all our members through our mailing list that will be curated by our communications committee. Through the Twitter account and the newsletter, we will share recent publications of our members and upcoming events, but also share other news or announcement of relevance to the community. If you would like us to share your publication or you came across an event that might be of interest to our members, please let us know – by e-mailing to ehpsdigitalhealth@gmail.com – so we may be able to include your item in one of the first newsletters already! In addition, we will use these platforms to inform our members about calls for contributions for future SIG activities and initiatives which will be coordinated by our events committee consisting of Laura Maenhout and Olga Perski. First activities are already being discussed, so stay tuned for more information very soon!

Join us!

When you are a member of the EHPS, you can join our SIG by contacting Ann deSmet, our membership officer, at ehpsdigitalhealth@gmail.com.

Food for thought!

We would very much like to welcome your input, in general, but especially concerning the following questions:

- What SIG activities would you be interested in?

- What are current challenges in the field of digital health that a collaborative initiative could target?

We are looking forward to your suggestions.

Bios

Dr Laura M König (@lauramkoenig) is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Konstanz, Germany. She is the co-chair and social media officer of the EHPS Special Interest Group on Digital Health and Computer-Tailoring (@EHPSDigiHealth). Her research focuses on how to promote the uptake and prolonged use of mobile interventions for eating behaviour change. She is particularly interested in reducing participant burden by making interventions simpler and more fun.

Eline Smit (@smit_eline) is an assistant professor at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research/ASCoR, University of Amsterdam. She is the chair of the EHPS Special Interest Group on Digital Health and Computer-Tailoring (@EHPSDigiHealth) and the secretary of the Amsterdam Center for Health Communication. Her main research interests concern tailored digital health communication, the integration of digital health interventions into the healthcare setting and the exploration of novel tailoring strategies, such as message frame tailoring. She has an extensive track record of peer-reviewed articles and has obtained several grants for research projects in this field, among which a prestigious Veni grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Close

Close