SMARTFAMILY – mobile health behaviour change in the family setting

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 30 November 2020

Written by Dr. Kathrin Wunsch and Janis Fiedler on behalf of the SMARTFAMILY project

Everyone knows that a lack of physical activity, too much sedentary time (e.g., extended screen time and nonactive media usage), and an unhealthy diet are serious concerns in modern societies as they accelerate the development of non-communicable diseases, which are causing millions of deaths every year. Research has repeatedly shown that human beings do not sufficiently engage in physical activity and frequently make unhealthy food choices throughout their entire lifespan. Therefore, it is of great interest to public health policymakers to reverse this trend at the earliest possible life stage. Longitudinal studies have shown that behavioural patterns in childhood and adolescence are vital because of their influence on physical activity patterns in adulthood.

As health behaviours in childhood and adolescence are to a large degree formed by parental behaviours, it is fundamental to target whole families. Research shows that supportive interactions within the family setting and shared values about health behaviour affect children’s physical activity engagement and eating behaviour. This has two major advantages: 1) the provision of early interventions can enable children and adolescents to adapt a healthy lifestyle, which they will likely transfer into (older) adulthood, and 2) by targeting both adults and children, there’s the added benefit of parental support, which is an important correlate of healthy behaviour in youth, and adults are also capable of behaviour change towards an active lifestyle.

As so many people today have access to the internet (4.5 billion active internet users in 2020 worldwide) and mobile Health (mHealth) interventions are popular – especially in young people – we decided to use mHealth technology to reach as many families as possible and to provide a cost-effective behaviour change intervention. Specifically, smartphone-based apps offer a great promise for enhancing physical activity and healthy eating as well as for making health care more accessible and scalable, more cost-effective, more equitable, and offer multiple opportunities for new, sophisticated developments.

But what are the key facets to include when developing such an intervention? To answer this question, we conducted an umbrella review of mHealth interventions targeting physical activity and healthy eating. Overall, findings suggested that the majority (59%) of e- and mHealth interventions were effective and used a theoretical foundation. In addition, we identified behaviour change techniques that were potential moderators of intervention effectiveness. However, most studies did not assess the impact of embedding interventions into social contexts (e.g. involving family members, peers or co-workers in the intervention). We did not see any mention of ‘ecological momentary interventions’ or ‘just-in-time adaptive interventions’ – i.e. interventions delivered at the right moment in time for each individual – in this umbrella review. With the possibility to tailor and to continually adapt mHealth interventions to each person’s unique needs, as well as to deliver support at the most promising moment in time, these parameters were identified by many study authors as being important to incorporate in new app designs.

With SMARTFAMILY, we wanted to fill these research gaps. As we identified mHealth to be a promising approach in our review and due to the known influence of parental support on early child and adolescent physical activity, we created an app that included all of these elements. Our app was developed based on social-cognitive and self-determination theory and included several behaviour change techniques. Importantly, we embedded the intervention in the social setting (i.e., the family) and enabled family members to set collective (instead of competitive) goals for physical activity and healthy eating. Our hypothesis is that by targeting multiple behaviours in multiple people, who can support each other to achieve goals, it should be easier to implement and maintain behaviour change. Moreover, we included gamification features into the app to enhance user engagement along with a just-in-time adaptive intervention approach and ecological momentary assessment features.

SMARTFAMILY is an app for the whole family (see Figure below), which incorporates the following features:

– an interactive goal-setting coach which provides useful facts to improve health literacy and supports goal setting within families

– device-based measured physical activity of participants with immediate feedback on goal achievement, in addition to the option to manually enter physical activity where the accelerometer has not been worn (e.g. during swimming)

– self-reported meals, common meals and common physical activity as well as physical activity where the sensor has not been worn (e.g. swimming)

– triggered and app-based ecological momentary assessment for physical activity and healthy eating; real-time measurement of behavioural and affective correlates of physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake, including current mood, stress, and exhaustion

– push notifications about inactivity sent by the coach when the participant is inactive for at least 60 minutes during waking hours (i.e. when the system detects that neither <2 sensor values at >2MET nor 100 steps has been achieved) – i.e. a just-in-time adaptive intervention; notifications are inhibited the rest of the day if the participant reaches at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on the respective day

– a sleep-mode set by participants before going to bed and after waking up, providing the time frame during which the app was used and a resting time estimation

– gamified goal achievement, where participants gather stars for every 10% of progress towards the weekly physical activity and healthy eating goal. The goal setting coach motivates the family to achieve their goals by prompting a “this far to go” summary every morning after waking up. In addition, the families are advised about a promising goal for the following week depending on their previous goal achievement by the coach.

Source: SMARTACT

Overall, we aim to close identified research gaps by evaluating an mHealth app which is theory-based, incorporates several behaviour change techniques, takes the social context into account and uses sophisticated new approaches like gamification, just-in-time adaptive interventions and ecological momentary assessments in a cluster randomized controlled trial design. We expect that our research will shed light on the important factors for health behaviour change in families and help to design more efficient interventions for (early) primary prevention in the future.

More information about SMARTFAMILY (@SMARTFAMILY9):

SMARTFAMILY is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research Grant FKZ 01EL1820C within the SMARTACT consortium (PI Prof. Dr. Britta Renner), with Prof. Dr. Alexander Woll, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany, as PI of SMARTFAMILY. Besides the PI and the authors, Tobias Eckert as well as our student staff needs to be acknowledged as being part of our project.

http://www.sport.kit.edu/smartfamily/index.php

https://www.uni-konstanz.de/smartact/

Bios

Dr. Kathrin Wunsch (@KathrinWunsch) is a post-doctoral researcher and Project Lead (@SMARTFAMILY9) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Her research focuses on influences of physical activity and multiple health behaviours on psychological and physiological health throughout the lifespan as well as on the development and implementation of mobile health interventions.

https://www.sport.kit.edu/english/4138_Kathrin_Wunsch.php

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kathrin_Wunsch

Janis Fiedler (@FieJanis) is a doctoral student at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. His research focuses on mobile behaviour change interventions to enhance physical activity and healthy eating as well as different aspects of exercise physiology. In general, he is very interested in anything related to primary prevention, physical activity and nutrition.

How can we use behavioural science to increase the uptake of the NHS COVID-19 track and trace app in England and Wales?

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 13 October 2020

Felix Naughton and Dorothy Szinay discuss how the uptake of contact tracing apps during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic could be increased by drawing on what we know about factors that influence people’s uptake of health apps more generally.

From the 24th September 2020, the NHS COVID-19 track and trace app was made available for use by individuals living in England and Wales.

From a technological point of view, it could be argued that the timing of the COVID-19 pandemic is quite fortunate: smartphone ownership is widespread in the UK and globally, and can act as a powerful tool for containing the spread of the disease. In the UK, around 80% of people currently own a smartphone. Using the phone’s Bluetooth functionality, contact tracing apps (such as the NHS COVID-19 track and trace app) can estimate when and for how long people running the app on their phones spend time together in close proximity. Then, if any of those people test positive for COVID-19, the app can alert those who have spent sufficient time with the infected individual, asking them to self-isolate to reduce the risk of onward transmission.

On paper, the COVID-19 app sounds like a critical tool in the fight against the virus. However, a key factor influencing the impact of a contact tracing app is its adoption rate in the population, i.e., the proportion of people that select to download and run the app on their phones. Contrary to an incorrect assumption that 60% of the population needs to use the app for it to suppress the virus, benefit can still be gained at low levels of adoption. However, the benefit is much greater at higher levels of uptake and ongoing use. As uptake (i.e., downloading and installing an app) is primarily a behavioural issue rather than a technological one, we should draw on behavioural science to better understand factors that influence app uptake and devise strategies to improve it.

Recently, we reviewed all the studies we could identify that investigated psychological and behavioural factors that might influence the uptake of and engagement with health and wellbeing apps. We further conducted an interview study to deepen our understanding. Several important factors were identified. Below, we revisit these factors and consider the implications for the NHS COVID-19 app.

A key factor is app literacy. When individuals have less skill and confidence in their use of apps, they are less likely to install and use them. Although the setup of the NHS COVID-19 app is relatively straightforward, people may still expect it to be complicated to use, which can put them off installing it. The complexity in how the app senses other app users and anonymously alerts them could translate into concerns that using the app will require advanced app skills and competence. It is therefore important that the most vulnerable subgroups in society, including the elderly, receive help to install the app.

Social influence has a big impact on the uptake of apps in general and will likely be an important factor in the uptake of the NHS COVID-19 app. Social influence includes things like other people’s ratings and reviews on app stores, and recommendations from loved ones, friends, health practitioners, and even celebrities. The team that developed the app reports having conducted research with Black and minority ethnic (BAME) communities to find out optimal ways to increase app uptake. One suggestion was to involve influencers within the BAME community in the dissemination of the app. Social influence, however, can be a double-edged sword. Negative reviews on app stores have the potential to undo positive influence. Furthermore, sceptical views or concerns among family and friends could damage uptake intentions. Another type of positive social influence is the use of a credible source: having the app developed by a trusted organisation and endorsed by the NHS and influential scientists and public health organisations, should help increase uptake. Participants in our interview study suggested that the promotion of health apps through a newsletter sent by GPs or family physicians would encourage them to use health and wellbeing apps.

Another factor is the availability of apps. While not having access to an app is an obvious barrier, it is an important one. In the case of the NHS COVID-19 app, while it is availabile in the two major app stores (i.e., for Android and iPhone users), it is not available to the small minority with other types of smartphones. Even among those who can use the compatible app stores, we estimate that 4% of Android users and 25% of iOS users have a phone running an operating system version that is too low to run the COVID-19 app (i.e., below Android version 6 and iOS version 13.5). We know that smartphone ownership is lower among those who are older, and we also anticipate that a larger proportion of older adults own smartphones with older operating systems compared with younger people.

Having adequate user guidance is a factor that can affect both the uptake of and engagement with health and wellbeing apps. For example, understanding QR codes is a requirement for checking into venues using the NHS COVID-19 app. Anecdotal user reports during the piloting phase of the app in Newham, London, suggested that many people didn’t understand how to use QR codes. It is therefore important to provide easy to understand instructions for how to use track and trace apps.

Another perhaps obvious but no less crucial factor is app awareness. Although we live in a world where information can travel fast, advertisements and media reports won’t reach everyone. When it comes to the NHS COVID-19 app, there has been an intensive mass media campaign to raise awareness, which means that many people would have heard about the app. However, the reliance on digital platforms for spreading information about the app might have excluded key groups who typically have low engagement in the online world. As people tend to forget information rapidly, it’s important that efforts to raise app awareness are sustained over time.

The perceived utility of the app was another key factor identified in our review. This includes providing a clear description of what the app does, what it can offer to the user and how it can help the user achieve their goals. One challenge with the NHS COVID-19 app is that its use generally benefits others rather than oneself. Some negative reviews on the app stores have highlighted this. In terms of detailing what the app does, the description clearly describes the features included. In our interview study, we found that highlighting the benefits of the app early on may prompt uptake. For instance, it might be useful to have the message ‘Protect your loved ones. Please download the app’ appear at the start of the app description as opposed to at the end.

Data protection is also an important factor. While the privacy policy for the app is well described, it is not that easy to get to. It is also very important to explain in non-technical language how the anonymity of the users is assured, which is likely to be a barrier to uptake and reduce trust. This has not been helped by the government’s refusal to make the findings of the pilot study public, which has led the Health Foundation to call for greater transparency.

Emotions may also play a role in app uptake. Our review found that curiosity, such as people seeing promotions of the app and feeling curious about trying it, may prompt them to download it. Anxiety was found in our interview study as another reason why individuals may want to use a health app, with the perceived threat of COVID-19 to one’s health or the health of others is a good example of this.

In sum, to maximise the uptake of the NHS COVID-19 track and trace app, evidence from behavioural science suggests the following:

- provide practical support either for enhancing app literacy skills or by providing user guidance

- ensure sustained promotion of the app through multiple channels simultanouesly (i.e., social and digital media, celebrities and influencers, primary care)

- facilitate the experience of relevant emotions when people hear about the app

- highlight the benefits of the app

- ensure transparency about data protection

- explain how anonymity is maintained using non-technical language

Bio:

Felix (@FelixNaughton) is a Health Psychologist and a Senior Lecturer in Health Psychology within the School of Health Sciences, University of East Anglia. He has a key interest in the development and evaluation of mobile phone interventions to promote and support health behaviour change (mHealth), particularly those promoting smoking cessation. He is also the co-lead of the COVID-19 Health Behaviour and Wellbeing Daily Tracker study https://www.uea.ac.uk/groups-and-centres/addiction-research-group/c19-wellbeing-study

Dorothy (@DorothySzinay) is a final year PhD candidate at the at the School of Health Sciences, University of East Anglia. Her research focuses on developing ways to increase the uptake of and engagement with health and wellbeing smartphone apps.

Mitigating sex and gender biases in artificial intelligence for biomedicine, healthcare and behaviour change

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 20 July 2020

Written by Dr Silvina Catuara Solarz on behalf of the Women’s Brain Project

Over the past two decades, there has been an emergence of digital health tools for the prevention and management of chronic disease arising from both the academic and industry sectors. A particularly prolific area is digital health tools relating to the promotion of mental health as well as physical health, with a focus on behaviour change and habit formation.

A central role in the advancement of these digital health tools is played by Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems, which aim to identify patterns of behaviour and provide personalised recommendations to the user according to their profile, with a view to optimising health outcomes. Al is also accelerating the progress on a myriad of complex tasks in the biomedical field, such as image recognition for diagnosis, identification of gene profiles associated with vulnerability of disease and prediction of disease prognosis based on electronic health records, that are aligned with the precision medicine approach.

AI and digital health tools are promising means for providing scalable, effective and accessible health solutions. However, a critical gap that exists on the path to achieving successful digital health tools is the robust and rigorous analysis of sex and gender differences in health. Sex and gender differences have been reported in chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, neurological diseases, mental health disorders, cancer, and there are plenty of health areas that remain unexplored.

Neglecting sex and gender differences in both the generation of health data and the development of AI for use within digital health tools will lead not only to suboptimal health practices but also to discrimination. In this regard, AI can act as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, if developed without removing existing biases and accounting for potential confounding factors, it risks magnifying and perpetuating existing sex and gender inequalities. On the other hand, if designed properly, AI has the potential to mitigate inequalities by accounting for sex and gender differences in disease and using this information for more accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Our work, recently published in npj Digital Medicine, focuses on the existing sex and gender biases in the generation of biomedical, clinical and digital health data as well as AI-based technological areas that are largely exposed to the risk of including sex and gender biases, namely big data analytics, digital biomarkers, natural language processing (NLP), and robotics.

In the context of mental health and behaviour change, some efforts have been made to include a sex and gender dimension to the implementation of theoretical frameworks for social and behaviour change communication. Still, further collection of data of the influence of sex and gender on aspects such as user experience, engagement and efficacy of digital health tools will provide a valuable starting point for the identification of optimal paths for efficient and tailored interventions.

Active and passive data input from users can be explored to derive sex and gender-associated insights through NLP and digital phenotyping. While these insights will shed light on how to optimise digital health tools for individual users, attention must be paid to potential biases that may arise. For example, NLP inferences from textual data used for training algorithms (an approach that is frequently used by mental health chatbots) are known to incorporate existing sex and gender biases (e.g. gendered semantic context of non-definitional words like ‘babysitter’ or ‘nurse’).

To avoid undesired biases, we strongly recommend pursuing ‘explainability’ in AI. This refers to activities focusing on the uncovering of reasons why and how a certain outcome, prediction or recommendation is generated by the AI system, thus increasing the transparency of the machine decisions that are otherwise unintelligible for humans.

Finally, we advocate that awareness of sex and gender differences and biases is increased by incorporating policy regulations and ethical considerations at each stage of data generation and AI development, to ensure that the systems maximise wellbeing and the health of the population.

Finally, we advocate that awareness of sex and gender differences and biases is increased by incorporating policy regulations and ethical considerations at each stage of data generation and AI development, to ensure that the systems maximise wellbeing and the health of the population.

This article was written on behalf of the Women’s Brain Project (WBP) www.womensbrainproject.com, an international non-profit organisation based in Switzerland. Composed largely by scientists, WBP aims at raising awareness, stimulating a global political discussion and performing research on sex and gender differences in brain and mental health, from basic science to novel technologies, as a gateway for precision medicine.

Questions:

- Is sex and gender accounted for in available behaviour change apps ?

- Is sex and gender considered in the frameworks used in the evaluation of effectiveness of behaviour change apps ?

- What are the risks of excluding sex and gender data when developing and evaluating behaviour change apps? What are the potential privacy challenges associated with their inclusion?

Biography

Silvina Catuara Solarz holds a PhD in Biomedicine specialised in Translational Neuroscience by the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona, Spain) and currently works as a Strategy Manager at Telefonica Innovation Alpha Health, a company focused on digital mental health solutions. As a member of the Women’s Brain Project executive committee team, she performs research on innovative technologies and their role in understanding sex and gender differences in health and disease. Her main interests include the application of digital technologies and AI into products to prevent and manage health conditions in a personalised and scalable way.

Find Silvina here:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/silvina-catuara-solarz/

The Human Behaviour-Change Project: Launch of new Wellcome Open Research collection

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 11 June 2020

Written by Dr Emma Norris & Professor Susan Michie on behalf of the HBCP team

Behaviour change is key to addressing many of the challenges facing the human population (e.g. reducing carbon emissions, preventing overuse of antibiotics, stopping tobacco use and reducing transmission of infectious diseases). A huge amount of information is being gathered on how best to achieve this in different situations but we have very limited capacity to collate it, synthesise it and use it to make recommendations.

What is the Human Behaviour-Change Project?

The Human Behaviour-Change Project (HBCP) is a Wellcome-funded project aiming to support decisions about behaviour change interventions using cutting-edge Artificial Intelligence (AI). The project aims to largely automate the process of collating, synthesising and interpreting evidence from the vast and growing literature on behaviour change intervention evaluations.

The project is a collaboration between behavioural and computer scientists and system architects that aims to create an AI-based Knowledge System that will scan the world’s published reports of behavioural intervention evaluations. This system will extract and analyse relevant information on interventions and their effectiveness organised using a ‘Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology’ (BCIO), developed as part of the project. You can read more on what ontologies are and how they can be used to structure knowledge here.

The Knowledge System will answer user queries and make recommendations as to what interventions are likely to work in a given scenario. It will also outline the level of confidence in and explain the process behind its answers. The first behaviour we are investigating is smoking cessation, drawing on published reports of randomised controlled trials.

The key activities involved in the project are to develop:

- An ontology of behaviour change interventions and evaluation reports: the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology (BCIO).

- An automated system to extract information from behaviour change intervention evaluation reports using Natural Language Processing.

- A representation of that information structured according to the BCIO.

- Reasoning and Machine Learning algorithms to synthesise this information and make inferences in response to user queries.

- An interface for computers and human users to interact with the system.

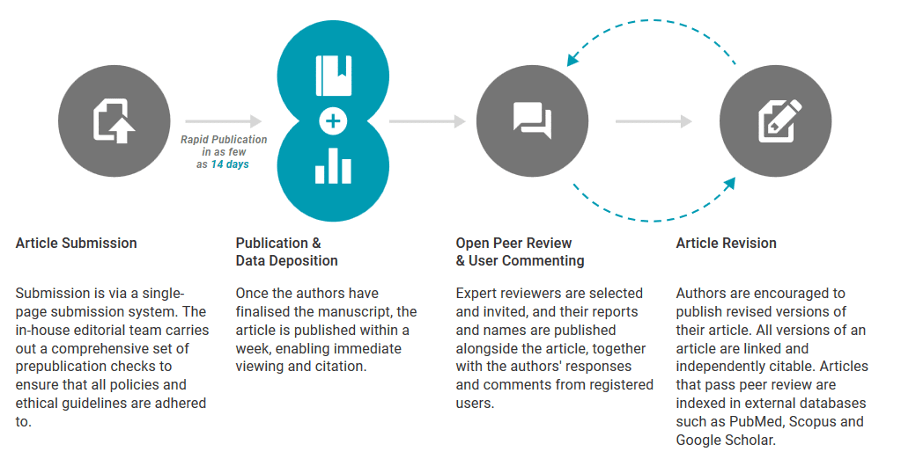

We have now completed various parts of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology and are publishing these as the first papers in a collection within Wellcome Open Research.

Why are we publishing this collection in Wellcome Open Research?

In behaviour change, open access to knowledge is essential to enable the development of effective interventions by researchers, policy-makers and practitioners. The establishment of effective health interventions benefits all. We want to publish our key findings in one easily accessible place, providing free access to all the outputs from the project. Wellcome Open Research is a platform where all articles are made publicly available upon submission, before a transparent peer review process and a final Open Access version.

We are also making our methods, working papers and resources available via Open Science Framework. We would like to receive feedback on our papers via Wellcome Open Research. The HBCP is a huge undertaking and it will require involvement of much of the research community working together to advance it at the speed required.

We are also making our methods, working papers and resources available via Open Science Framework. We would like to receive feedback on our papers via Wellcome Open Research. The HBCP is a huge undertaking and it will require involvement of much of the research community working together to advance it at the speed required.

Articles included in the collection so far

Our initial launch of papers in the collection contains five papers:

- Editorial – introducing the project.

- Methodology paper – explaining the methods we used for ontology development.

- Upper-level Ontology paper – specifying the overarching structure of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology.

- Mode of Delivery Ontology paper – describing a part of the BCIO that characterises ways that behaviour change interventions are delivered (e.g. by face-to-face contact, websites, video)

- Setting Ontology paper – describing a part of the BCIO that characterises the locations in which interventions are delivered (e.g. what country they are in, whether they are in hospitals or primary care)

We will continue to publish papers in the collection as other parts of the project are completed, with several currently in the pipeline.

You can find more information on the Human Behaviour-Change Project on our website and Twitter.

Questions for discussion

- What are your thoughts on Open Access publishing and peer review?

- How could outputs from the Human Behaviour-Change Project be useful to your work?

Biography

Dr Emma Norris (@EJ_Norris) is a Research Fellow on the Behavioural Science team on the Human Behaviour-Change Project at UCL. Her research interests include the synthesis of health behaviour change research and development and evaluation of physical activity interventions.

Professor Susan Michie (@SusanMichie) is Principal Investigator of the Human Behaviour-Change Project, Professor of Health Psychology and Director of the Centre for Behaviour Change at UCL. Her research focuses on developing the science of behaviour change interventions and applying behavioural science to interventions. She works with a wide range of disciplines, practitioners and policy-makers and holds grants from a large number of organisations including the Wellcome Trust, National Institute of Health Research, Economic and Social Research Council and Cancer Research UK.

World 2.0: After COVID-19 another world is necessary, and possible

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 16 April 2020

Written by Dr David Crane

What is happening now is a mass, shared, life-changing psychological event. Potentially. The long-term effects of any event are of course impossible to predict for individuals. But on a global level, the substantial changes so-far wrought by this pandemic suggests COVID-19 could have a lasting effect on the behaviour of a large number of people.

In the space of three months, a threat has gone in public consciousness from theoretical to powerful enough to force billions of people to make fundamental changes to their daily lives. Behaviours unthinkable a short time ago, such as staying at home for weeks on end, are now so commonly accepted as to make being outside feel uncomfortable. Behaviours still largely unconscious, such as touching one’s face, somehow need to be changed because there is a non-trivial chance that something so simple and commonplace could now lead to our, or somebody else’s, demise.

Everything we are doing to develop a vaccine and change our behaviour will hopefully mean that when compared to previous pandemics the number of deaths will be low. And it is probably true that our ancestors had to live with more uncertainty on a regular basis than we are experiencing now. So why might this event be so significant psychologically? Because it could result in a paradigm shift in our awareness of the fragility of life and the benefits of collaboration. One experienced by a great many people over a large swathe of the world at more or less the same time.

The chance that we or our loved ones might die in the near future has, for most of us, gone from effectively zero to something noticeably greater in a short space of time. The risk remains mercifully small but cannot be dismissed entirely, even by the young, healthy, rich and/or powerful. Those who downplay the risk will still probably be more careful about keeping their distance and washing their hands, even when not demanded by new social norms. And if the only reason this is done is for fear of infecting others, that still represents a substantial change in threat perception since Christmas.

By the time this is pandemic is over, it is likely that almost all of us will know people who have died and others who have suffered, even if we escape suffering ourselves. Awareness of death’s proximity will be increased by the availability of its news. TV, newspapers and radio will tell us about people we have heard of who have died, or tragedies that people we can relate to have suffered. Social media will be full of heart-wrenching stories from people we know who have lost people they loved; the most moving of which will be shared more widely themselves, so enlarging the circle of grief far beyond usual bounds.

A subject many people prefer not to think about will be pushed into consciousness for a considerable period of time. Reactions will fall along a spectrum of course, from totally unaffected to completely petrified. Though many people unaffected by a change in their proximity to death are likely to be affected by one or other of the loss of their job (now or possibly soon), wider concerns about the economy, fears for what society is about to go through, worries for other people, or just that deeply unsettling feeling that many of the things that used to be relied upon are now less secure.

Something microscopic has seemingly come out of nowhere to upend our world with astonishing speed. Finding this a destabilising experience seems a perfectly appropriate response. This is a profound change.

But profound changes do not have wholly negative outcomes. Human beings have the inherent capacity – and tendency – to make life-altering events turn to our advantage. In normal times we carry on doing what we’ve always done until it’s abundantly obvious it no longer works. It can take years of disconfirming experiences before we accept that things which used to relieve pain or bring pleasure now have the opposite effect. And those are the big, noticeable, things. Much of our now ineffective behaviour is too small to be seen.

In exceptional times change is thrust upon us. Routines are forcibly broken, usual behaviour prevented. We can’t do what we’ve always done because it is impossible, impractical or obviously ineffective. Which makes it easier to see what’s as it should be and what needs adjustment. Behaviour that might otherwise be automatic and habitual (like drinking alcohol when stressed), is brought into awareness, from where decisions about whether to continue are more easily made. Opportunities to gain clarity on our priorities happen rarely in our lifetime, it is hard to think when previously they have happened to so many people at the same time.

A force multiplier of COVID-19 is that along with opportunity to change, it also provides a significant amount of motivation too. Because the virus only makes obvious that which has always, and will always, be true: life is fragile and the future is uncertain. It’s easy to procrastinate when we think we’ve got plenty of time. We tend to be more proactive when we realise that’s not so. This principle is something we understand intellectually and have probably experienced mildly. The difference now is how salient it could become.

In addition to opportunity and motivation, the third element for behaviour change to take place, capability, could also be increased by the pandemic. Or rather, by its survival. Simply getting through this will boost many people’s self-efficacy and sense of resilience and resourcefulness; with people who experienced more doubts likely to see greater increases than people who experienced few. Capability is also increased by motivation to change, which could increase substantially, and skills teaching, which is abundant.

Thoughts of everyone doing whatever they want may inspire fears of a hedonistic, anarchic, free-for-all. But if that were true, we would expect to see people being at least equally selfish when they felt most threatened. If our evolutionary tendency was towards self-interest, surely that would be more obvious when our survival was at risk.

But selfish behaviour does not appear to be prevalent. The opposite, in fact. Millions of people are risking their lives so we can live ours. Hundreds of thousands of support groups have spontaneously formed so people can look after each other. Acts of generosity and thoughtfulness abound, amongst friends and strangers alike. This represents, I suggest, large-scale evidence of enlightened self-interest: the understanding that our interests are best served by helping others. Because there is nothing like feeling vulnerable to make us realise how much we need other people. And perhaps nothing has made more people feel more vulnerable than this.

By talking about positive outcomes I do not mean to belittle the great suffering that will occur. Many people will be left in dire circumstances as a result of this crisis, some may never fully recover from losing people they love, others might find the threat too overwhelming to deal with, let alone make the most of. We cannot forget that a great many people will need help through and after this.

We also should not expect positive change to be guaranteed. Bad actors will seek to use this for their benefit. Our motivation to change will fluctuate and we should anticipate resistance internally and from others. Changing behaviour takes time and requires persistence. It does not come easy on an individual level, let alone a societal one.

Reasons for optimism come from three places. First, we are not talking about people having an intellectual appreciation of why change is important, these are visceral experiences, which are usually more salient. Second, even if only a tiny percentage are driven to change, that still represents a very large number in absolute terms. Third, the visceral experience large numbers of people are having is unlikely to be for more separateness. We might hope.

The world before COVID-19 seemed headed towards greater inequality and protectionism. What we are presented with now is a lesson in cooperation. To get through this crisis we need strangers to risk their safety to take care of our health, keep us supplied and perform the other services we now know are essential. Almost everyone has agreed to make sacrifices to prevent the transmission of disease, even those who feel the risk to themselves be small. Perhaps most importantly, the opportunity to help others allows a great many more of us to experience the primal boost to self-worth that comes from feeling of value.

We sometimes forget that we are a group species whose success lies more in our ability to cooperate than compete. Competition doesn’t work in a crisis, challenges like these can only be overcome by working together. The experience of this even being possible, how good it feels and how effective it can be, is perhaps what is needed for us to address the even bigger challenges the world will soon face.

Dr David Crane is founder of the popular smoking cessation app, Smoke Free. His interest in behaviour change started in primary school and hasn’t really stopped since.

Close

Close