Using behavioural science to increase engagement with online learning: Reflecting on a term of online delivery

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 15 December 2020

Written by Dr. Danielle D’Lima, Senior Teaching Fellow for the MSc in Behaviour Change at University College London.

Due to the global pandemic, I have spent a lot of time thinking about converting the face-to-face versions of our core modules to online versions. To accommodate learners from across the globe and make best use of online pedagogy, I took the approach of dividing the content into a mixture of asynchronous and synchronous online learning activities.

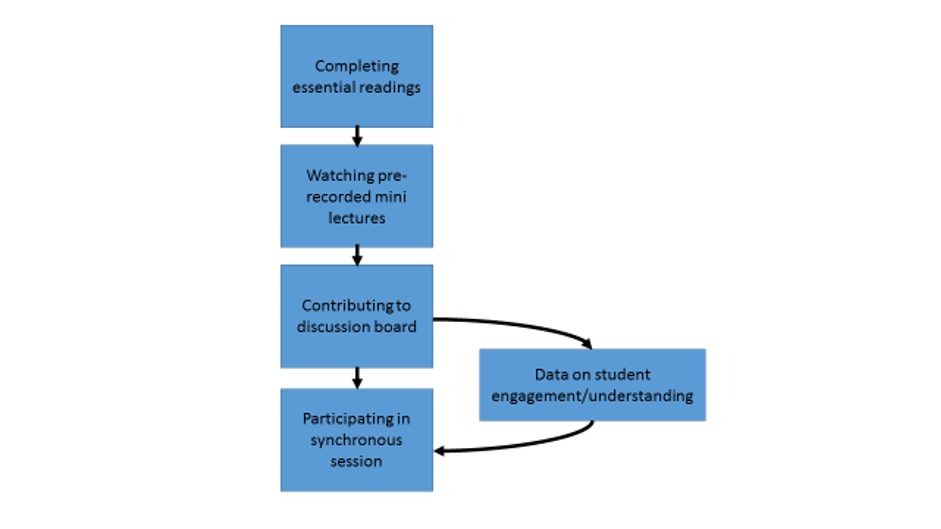

Asynchronous activities consist of essential readings, watching short pre-recorded mini-lectures and contributing to online discussion boards. These can be completed in students’ own time and pace, and are followed by a two-hour synchronous seminar in which students are supported to complete small group tasks in break-out rooms and receive some additional content developed by us based on the ‘data’ accumulated from their discussion board contributions.

This blog post offers some reflections from my experience of a term of online delivery of behaviour change teaching and considers how behavioural science itself can support us in further increasing student engagement with online learning in the future.

Over the summer of 2020, I worked on translating the teaching materials for online delivery, including chunking the lecture content to create a series of pre-recorded mini-lectures. To chunk the lecture content, I began by reviewing all of the lectures that I usually give on each module and separating the content into ‘meaningful’ sections. A meaningful section equates to a chunk of learning that stands alone but is clearly connected to what comes before and after it.

I went through several iterations of chunking in this way and recording, as I found that recording a section sometimes made me think about chunking it in a different way, and this had implications for the overall organisation of the material. The final pre-recorded mini-lectures ranged in length according to the content and purpose. For example, some took three minutes to introduce a task for the discussion board or prepare students for the upcoming synchronous session, right up to twenty minutes to cover key content for the week’s learning objectives. I was excited to undertake this exercise as I was drawn to the idea of categorising the content and reassessing it against the learning objectives. I then continued to make small iterations week by week to ensure that I could adapt and develop the mini-lecture chunks based on my experience of teaching the new MSc cohort, and the feedback I received from students across the term. For example, for Week 2, I added a short mini-lecture chunk which contained some reflections on Week 1 and additional examples to support further learning.

How has it gone so far?

The experience of Term 1 (October-December 2020) has been really positive. I have gained so much as an educator that I would not have got from delivering the content face-to-face. Despite regularly reflecting on the individual lectures that I give and how to improve them, it is sometimes difficult to see the relationships between smaller chunks of information (and the learning activities that they are nested in) after having delivered the entire content.

This approach has also helped me to address some of the specific teaching challenges that come from having a very mixed student audience from different disciplinary backgrounds. Our course covers multiple theories and models of behaviour change. Some students have relatively advanced experience and understanding of certain theories and models (e.g. those that have come to the MSc directly from a psychology undergraduate degree). However, we also have many students (around half) on our course who come from other disciplinary backgrounds (e.g. economics, arts, law, politics, history, business, and health) and therefore come to the module with no or very little prior knowledge of these theories and models.

Through the process of chunking the lecture content, I organically began to identify components that were of particular relevance to different subgroups of students (i.e. those with more or less prior knowledge or experience). I was therefore able to highlight this in my audio by clearly signposting who it was most relevant to. I could also tailor the learning where appropriate by creating and highlighting particular recordings that go into more detail on some of the theories and models. This has hopefully helped students to better understand the position that they are sitting in within the cohort, and how they can ensure that they take what they need from the pre-recorded mini-lecture chunks; it gives them autonomy to engage with the material in a way that best suits their learning needs.

I have noted that this tailored approach also has a positive impact on the synchronous sessions that I am running. For example, students are able to join the session with the right level of information to engage fully in the interactive group tasks, and I am able to join the session with prior information on how students have engaged with the asynchronous activities and the extent to which they have met the learning objectives. By having access to the ‘data’ on the discussion board in advance of each synchronous session, I have been able to proactively tailor the session in a way that I would not when delivering the lecture and seminar as part of the same face-to-face session. This offers an additional safety net to ensure that the learning objectives are successfully met for all students.

Where next?

After receiving positive and encouraging feedback from our students, I plan to take the same approach to online teaching in Term 2. However, the next module, “Behaviour Change Intervention Development and Evaluation”, will present slightly different challenges. For example, it is a highly interactive module that relies on students having the time and space to practice key skills for intervention design. I anticipate that chunking the material will help me to identify exactly which components of the material are essential for setting students up to practice and develop the skills – either independently or as part of synchronous group work – interspersed with formative feedback.

Summary of techniques used to increase engagement with online learning:

- mixture of asynchronous and synchronous activities

- chunking of lectures

- feedback

- signposting

- tailoring

- autonomy

How can behavioural science support us in further increasing student engagement with online learning?

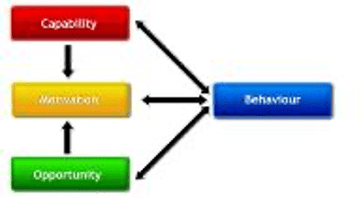

As behavioural scientists, we have a unique advantage in understanding what students might need in order to engage with online learning. Engagement, after all, is a behaviour or set of behaviours and we know that in order to enact a behaviour people require capability, opportunity and motivation!

I include below some early reflections on what capability, opportunity and motivation might look like in the context of engagement with online learning and how we, as educators, could go about better supporting our students. These ideas are not intended to be exhaustive but instead food for thought about how we can better apply our skills as behavioural scientists when designing and delivering online education.

Capability

Students require the necessary knowledge and skills to engage with online platforms and complete the required learning activities. Clear communication to students regarding what they need to do and how they should go about doing it is essential. For example, this may involve sending a weekly alert to students explaining exactly what is expected of them in advance of the next synchronous session. Allowing students to practice interacting with the online learning environment can also go some way in supporting development of the necessary skills.

Opportunity

With numerous learning activities being allocated to students from multiple modules, there is a risk of them becoming overwhelmed. Students require sufficient time and resources to complete the learning activities (e.g. engage with the materials in advance of live sessions) and this needs to be incorporated into the planning of the activities (e.g. ensuring materials are available with sufficient time). Students also need reliable online learning platforms that are well designed and easy to navigate.

Motivation

It is important that students understand how learning activities were designed and why they are worth engaging with. By clearly communicating the rationale to students, where appropriate, educators can help them to identify the potential outcomes of their efforts. It is also important that students are rewarded for their efforts. For example, by providing informative responses to student discussion board posts and using key themes from the discussion board activity to develop teaching content.

Of course, educators themselves also need the capability, opportunity and motivation to demonstrate the behaviours required for successful online teaching (e.g. pre-recording a lecture, creating learning activities, communicating to students, etc.). But I will save that for another blog!

Bio

Dr Danielle D’Lima is the Senior Teaching Fellow for the MSc Behaviour Change at the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London. Her role includes designing and delivering teaching and training as well as overseeing research projects on implementation science and health professional behaviour change. She also has an evolving interest in the application of behaviour change science to teaching and training.

One Response to “Using behavioural science to increase engagement with online learning: Reflecting on a term of online delivery”

- 1

Close

Close

Thanks for the information you have provided through your blog.