The Smartphone Dilemma: Exploring Parental Decision-Making for 9-12 Year Olds

By CBC Digi-Hub Blog, on 10 May 2023

Written by Rachel Perowne, PhD Student (UCL Centre for Behaviour Change)

Children’s interaction with the online world is a hot topic – recently, The Economist magazine asked whether smartphones are to blame for recent increases in the rates of suicide among girls [1]. This week, the Children’s Commissioner for England published a report evidencing the effect of pornography on harmful sexual behaviour among children and suggesting a link between exposure to pornography and children being given their own phones at younger ages [2].

I was 21 when I got my first mobile phone and over 30 when I got my first smartphone, but today’s children and young people are growing up in the digital world where the concept of a ‘brick phone’ or landline is alien, and smartphones are the norm. As technology plays an ever-increasing role in our lives, it’s not surprising to learn that children are acquiring smartphones at a younger and younger age. To illustrate, in 2018, 35% of 8–11-year-olds owned a smartphone [3] and this had risen to 60% by 2022 [4].

So how do parents make the decision to give their child a smartphone?

This question fascinated me – both as a parent with a son approaching 11 years old and as a researcher interested in young people’s wellbeing in a digital world. I could hear many of my friends and peers with children of a similar age debating what to do and I took the opportunity, whilst waiting for my PhD to officially begin, to examine this, with the support of my supervisor Prof Leslie Gutman.

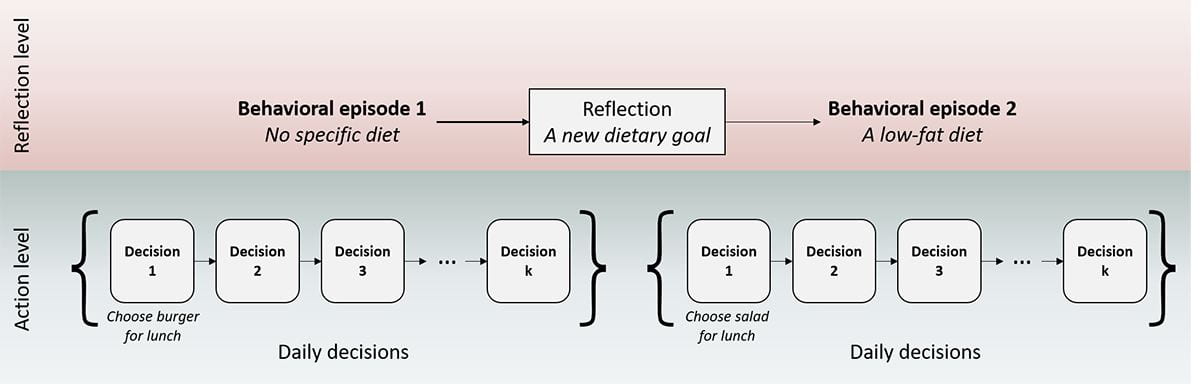

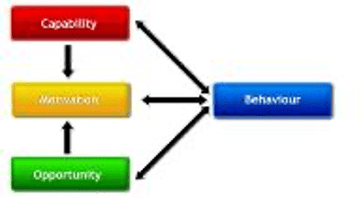

Our study, published this month, on parents’ perspectives of their children’s smartphone ownership [5], involved interviewing 11 mothers and fathers of 9- to 12-year-old children and using the COM-B model to identify which elements of Capability, Opportunity and Motivation were influencing their decision making.

Our analysis identified a number of influencing factors across all three COM-B domains:

- The external environment was a key enabling factor in parents deciding to give their child a smartphone; parents see smartphones as an inevitable aspect of the modern world that can only be resisted for so long because ‘technology is everywhere’.

- Added to this, the pressure of peers being given a smart phones – the social opportunity – creates a ‘domino effect’ which then affects parents’ motivation, making them want to prevent their children being left out and help them build their social relationships.

- They also see advantages in being able to track their child’s movements and ensure they are contactable once they start travelling independently to and from school. ‘When they… go to school by themselves, then obviously I need to give the smartphone’. Hence the transition from primary school is a key time for many children being given a smartphone.

- However, parents are conflicted. They also have worries about their children entering the world of smartphones and the unfettered access to the internet that this can bring. ‘Having his phone in his room at night is a big worry for me’.

- They worry about the impact of social media, about bullying, about overuse and addiction but are sometimes unsure of what the real benefits and risks are. ‘I think there are certain risks and I think there are certain benefits but it’s all kind of in my own head’.

This uncertainty is understandable. Evidence is mixed on the impact of smartphones on younger children, with many recognising that smartphones can support learning and increase digital skills which are important for life in a technological world. At the same time, whilst causal linkages are hard to demonstrate, correlations are apparent between smartphones and sleep disturbance, anxiety and academic performance. It seems clear that young people are also particularly prone to Problematic Smartphone Usage (where usage interferes with daily life and activities).

So where to go from here?

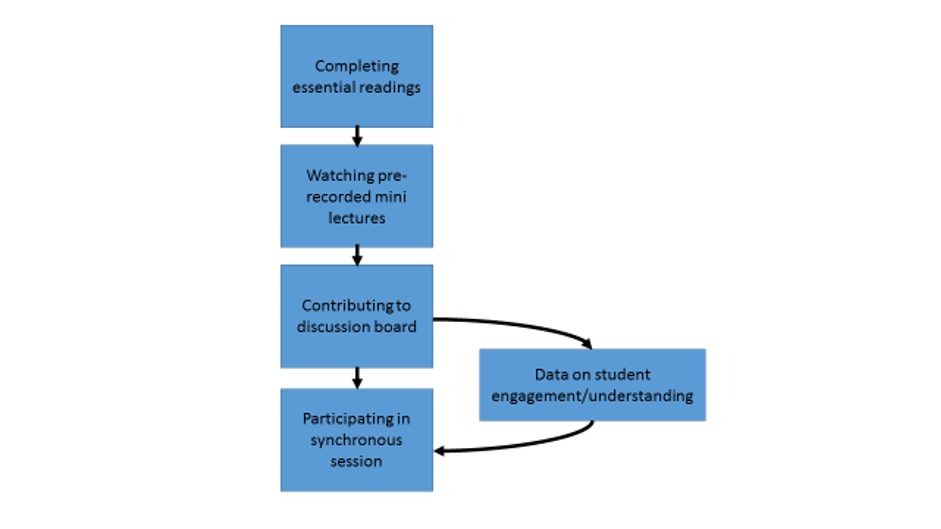

The parents we spoke to were grappling with their decision-making. They felt that there was a lack of guidance and support for them in planning how and when to give their child a smartphone. This challenge is heightened because their own digital technology skills and knowledge are often inferior to their child’s, meaning that their efforts to control usage and access can be undermined by a tech-savvy child. Our paper discussed potential intervention strategies (using the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) [6] including:

- Restrictions such as having a recommended minimum age for smartphone ownership

- Guidance and support for parents preparing and planning to give a child their first smartphone

- Education from credible sources on the benefits and risks of smartphones for children

- Training in setting up appropriate controls on a child’s smartphone

Whether there is a role for regulation and restriction (such as age limits) of smartphones is a debate that rages. In either case, it seems clear that expecting parents to navigate this significant decision on their own is too much. Given the potentially lasting impacts of owning a smartphone for children, better guidance and support from authoritative, trusted sources are required.

[5] Perowne, R., & Gutman, L. M. (2023). Parents’ perspectives on smartphone acquisition amongst 9-to 12-year-old children in the UK–a behaviour change approach. Journal of Family Studies, 1-19. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13229400.2023.2207563https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13229400.2023.2207563

[6] Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Eccles, M., Cane, J, & Wood, C. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behaviour change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95.

Close

Close