Isolated, not alone

In Brazil, 15.3% of people aged 60 years and over live alone. When I conducted my 16-month ethnography among older people in Sao Paulo, I came across many of them. Most are extremely active and engaged in social activities and in the WhatsApp groups I participated. They have many friends, enjoy their freedom and independence. However, there are also a few who are living in a kind of semi-quarantine. The reasons for this are many. Some are widows. Some chose not to have children, some had children, but the children moved abroad. Some self-isolated after retirement. Their social interactions are sometimes restricted to speaking to shop assistants and people at the market, the drugstore, and the bank. There are many nuances among people in those two groups, and I was worried about both when social distancing was imposed by the coronavirus outbreak. How could I help them? The answer came from my fieldsite, where I observed how people like Marta and Bete below, were using WhatsApp to create networks of care.

Marta, aged 54, told me she does volunteering work. Every morning she sends a “good morning” messages to three older ladies who she knows are leaving alone. The WhatsApp messages work as a daily check to ensure the three are doing alright, as well as being a demonstration of affection and bringing joy to them.

Bete, aged 66, experiences a similar routine, but with her daughter, who lives in Spain. Everyday the daughter waits for a message from her mother to arrive before 10 am, when the mother writes to confirm that she slept well and that she is fine. The same procedure is repeated at night. If Bete doesn’t answer the message, her daughter has some friends in Brazil that she can count on who can support her mother if necessary. In addition to this, Bete, who had an aneurysm two years ago, also receives occasional calls from her health insurance provider. During the call, she updates the doctors about the state of her health and receives advice. Despite living alone in São Paulo, far from her daughter and grandson, Bete feels safe and assisted.

I learned a few things from these simple, but successful models of care:

- They take place on a platform people are already used to (in the Brazilians’ case, this means WhatsApp).

- They are based on care providers who shift from a reactive to a proactive role (including family, friends, or institutions)

- They create a daily routine of care

- They show even simple text messages can make a difference.

Based on that, I created an awareness campaign which replicates those models and provides support to older people living alone during the coronavirus crisis. The campaign is called “Angels on WhatsApp” because “angel” was what some of my informants used to call me when I helped them solve a problem.

Prototyping Wings

The campaign was launched on the 14th of March on my social media channels, but my focus was my WhatsApp groups and people I knew working on the topics of ageing or health. The campaign consisted of an image and a text message with instructions on how to become an Angel for older people living alone during the quarantine.

There is a guardian angel on my WhatsApp. Adopt an older person who lives alone during the coronavirus crisis. All you have to do is to be available on WhatsApp. Acess: http://www.saudeeenvelhecimento.com.br

The message describing the campaign that was sent out to my contacts can be read below. Because the message was translated from Brazilian Portuguese, some of the content of the message will relate to Brazilian healthcare infrastructure.

AN ANGEL ON WHATSAPP, BECAUSE SOLIDARITY IS ALSO CONTAGIOUS 😇😇😇

Social distancing can be a great preventive measure against the Coronavirus, especially for the population over 70, which has the highest mortality rate. The feelings of loneliness, abandonment and helplessness that it can bring are an immediately visible downside. But that does not mean that older people have to go through this alone.

The idea of the initiative is simple: you can become a guardian angel on WhatsApp 😇 and help support older people who live alone. The idea can be applied anywhere in the world, but it is important to do as the virus would do, and start with the people you have contact with. So, forget your country, and forget your city. Think small: start with your WhatsApp contacts.

DO YOU KNOW OF AN OLDER PERSON WHO LIVES ALONE AND WHO IS ONE OF YOUR WHATSAPP CONTACTS? 👏👏👏👏👏👏👏 GREAT! NOW YOU CAN BE HIS OR HER GUARDIAN ANGEL:

👉 Text him/her in the morning and in the evening. Ask how he/she is, whether he/she slept well, whether he/she has eaten.

👉 Be available to chat.

👉 Be ready to guide him/her on how to seek medical advice. In Brazil, the Ministry of Health developed an app with a questionnaire for screening patients based on symptoms and a map of treatment centres using geolocation. Search for ‘CORONAVIRUS SUS’ in your app store.

👉 You can also keep him/her informed by sending news from reliable sources. The Ministry of Health has prepared a page on the Coronavirus that can be accessed here: https://www.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/coronavirus. The CORONAVÍRUS SUS app also offers reliable news and tips.

👀 PLEASE NOTE: the volunteer cannot make a diagnosis or give any medical recommendations. The volunteer is a bridge for connect older people to reliable information and professional medical assistance.

WHY IS THIS REALLY IMPORTANT? 💪💪💪💪💪

- You can help support older people and make them feel less lonely during their period of self-isolation due to the Coronavirus.

2. Two heads are better than one: you can both discuss the news about Coronavirus and double-check their reliability and trustworthiness before sending them on to friends.

3. The SUS application is really good, but one of the biggest difficulties older people (mainly over 70) have is downloading and installing new applications. You can be a bridge between an older person and the information and guidance contained in the SUS application.

WHERE DID THE INSPIRATION FOR THIS INITIATIVE COME FROM? 👽

My name is Marília, and this idea is based on my PhD research. For 16 months, I observed the use of smartphones among older people in Sao Paulo. If there is an app that they universally use, it is WhatsApp, including using the app to build networks of care and solidarity. Want to know more? Access: http://saudeeenvelhecimento.com.br/anjo/ (in Portuguese)

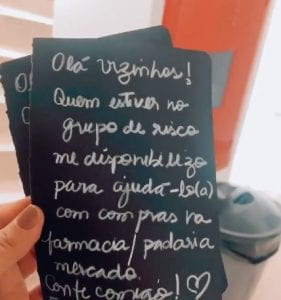

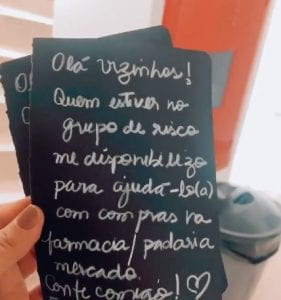

The message above went viral, and people I knew started asking me for older people’s WhatsApp numbers. Some of them decided to focus on their neighbours, reproducing the notes that were spreading all over the country[1]. Then, the campaign reached the media, and I ended up getting 150 emails from people interested in becoming an angel. That was how my problems started.

“Hello, neighbours! If you are in a risk group, I am available

to help by going to the drug store or market. You can count on me.”

From Heaven to Hell

On the one hand, I had 150 people wanting to volunteer. On the other, I had hundreds of older people I worked with and some I knew would be alone during the quarantine. So what did I do? Nothing. Firstly, I couldn’t breach the terms of confidentiality of my research. Secondly, because older people are a common target for scammers, I could only intervene directly when three older people wrote to me asking for an angel, when I managed to get close friends of mine who I knew were trustworthy, to take care of them. And what about the rest? I couldn’t take the risk of having a swindler mistaken for an angel, so I started looking for existing platforms that could facilitate this match between people. I found two.

The first one is the startup “Mais Vivida”, which connects young people who get paid to help older people with their shopping or computer skills, for example. Mais Vivida created a free service for the coronavirus crisis which puts volunteers and older people in touch for free, but their service has a problem. To ask for help, older people need to fill in a six step form on Google Forms. I tried to use Google Forms to create a survey for my research participants before. It didn’t work well, especially for those older than 75.

Screenshot from Google Forms used by Mais Vivida.

I continued searching and I found “Os vizinhos do Bem” (The Good Neighbours), a platform developed for the quarantine which matches those who can offer help to those who need help. In this case, the first question the website asks is why you are seeking help and there, the user has the option to inform the service that he or she is 60 or older. The questionnaire is simpler, with only 11 fields, but it could be still a challenge to complete for older people.

For now, I keep giving guidance to volunteers to check their WhatsApp contacts, to ask friends, and to pay attention to their neighbours and I am also encouraging them to engage with one of those platforms. In the perfect scenario, older people wouldn’t have to leave WhatsApp or install any other app to inform others that they want help. After teaching three semesters on a WhatsApp course, it was clear the platform is where they become connected, where they feel comfortable and confident. So I am still waiting to find an alternative which considers this ‘smartness from below’, but this won’t stop angels being angels. I keep receiving feedback from people and it confirms what one woman aged 66 once told me: “In volunteering, you think you are giving something, but you are the one who is always winning.”

Below, you can read the testimonials of some of the Angels who have taken part in the initiatives, where they reflect on their positive experience.

“When I discovered that an action as simple as sending messages, calling or video chatting with older people could make such a difference, I was overjoyed. I adopted three lovely “aunts” with whom I started to speak every day. Today, one got emotional and thanked me saying that before that, she only had her dog to talk to. Then I was the one who got emotional”. – E. S. Forbes

“At first, I thought that she did not need help, as she was very attentive and has children living in the same city. As the conversations went on, I came to that old truth – we all need it. We always learn that we can help others and that would fulfilment and calm the soul. We also learn that there is always something new to be learnt. Taking care of an “older lady”, even if virtually, also helped me to manage the absence of my own parents who are not here anymore. In the scariest moments, like the ones we are living in now, I think about them and what they would say to me. So now, I listen to my older lady. All of this also gave me that really made me want to help more, to send messages to those uncles we never speak to and to the neighbours in the building”. -S. Prevideli

Filed under Brazil

Tags: #care, communication, digital, elderly, isolation, living alone, older people, pandemic, sao paulo, support, technology, WhatsApp

No Comments »

Close

Close