Vulnerable margins or robust mainstream? Cocooners after lockdown

By paulinegarvey, on 18 June 2020

by Pauline Garvey and Bláthnaid Butler

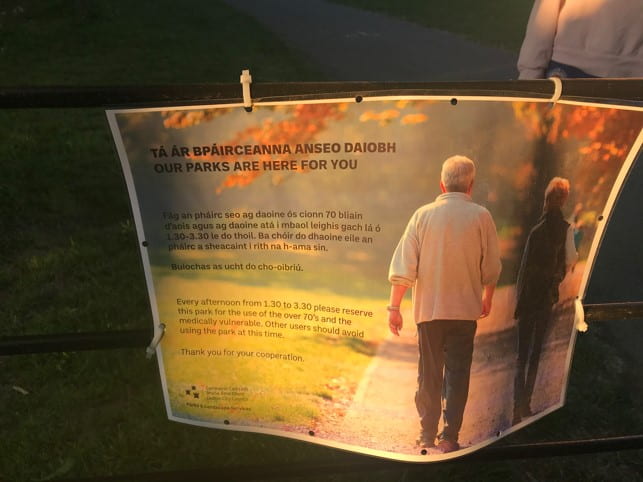

A Dublin City Council notice placed in public parks

After two months of lockdown, Covid-19 restrictions started to be lifted in mid-May in Ireland. Instead of having to stay at home or venture only 2 km from home, people were allowed to travel 5 km and then finally, anywhere in their own county. As in other countries, the sense of excitement was palpable and many Dubliners spoke of their sense of relief in being able to meet friends, albeit with social distancing and venture further than they had for several weeks. Sports reopened to a limited degree, particularly non-contact sports, and among them, golf clubs and tennis courts were opened. Debate continues about whether masks should be mandatory in supermarkets and on public transport. However, the measures put in place to protect older people who were cocooning is being received as a mixed blessing.

Some over-70 years old find themselves conflicted between recognising the necessity of cocooning on the one hand, while feeling pigeonholed in the category of ‘vulnerable’ on the other. Being ‘at risk’ implies being sheltered and protected but ultimately also denied the same freedoms as other members of society. One place where this was most visible was in the opening of sports clubs, particularly tennis courts, which were ‘off limits’ to the over 70-year olds. Aware of the bubbling controversy, chief executive of Tennis Ireland Richard Fahey commented that “We are aware that there is an issue. Over 70s feel they should be allowed to go out and play tennis. But they are not the only group that is restricted in this phase”[i]. People who see themselves as fit and agile thus find themselves excluded from their regular hobbies, not as something self-enforced but as an imposition for ‘their own good’. And this is a particular problem for those that do not see themselves as vulnerable or who consider that the category of vulnerable is too narrowly assigned to a chronological age rather than a health condition and which does not reflect their vitality and overall general health. This issue is central to our research in ASSA and discussed in detail in our forthcoming publications[ii].

It is not surprising, then, that when it comes to food, such issues arise and are frequently fraught. Anthropologists have long been aware that the rituals around food and producing meals is pivotal to the construction of the home and family[iii]. Mealtimes rules and routines create family roles and socialise family members. We learn about the duties of gender, care and morality through the work of provisioning and preparing food. But when is it appropriate to express reliance or autonomy? And when do practices of care transition from a help to a hindrance? One ‘cocooner’ complained that when she first emerged in the public sphere and walked around the shops, she sensed people were looking at her and that she didn’t feel welcome. She described her sense of surprise because she felt so self-conscious that she eventually retreated home.

During the lockdown, community organisations were mobilised to shop for cocooners. In Dublin, local community groups such as church groups, scouts and sports clubs set up groups on WhatsApp to shop and drop for people who needed help. Amongst families too it was common for adult children to bring weekly provisions to their parents so that they could stay home. While adult children prefer to do the shop because ‘it’s no bother’, we have found several instances where the parents prefer to be autonomous. One couple watered down their milk rather than ask their daughter to pick them up some more. Reasons for this included a mix of emotions such as fear of being a burden, exposing her to further risk and being prepared to make ‘small sacrifices’ or ‘do without’ because they decided it was ‘non-essential’. However, as soon as it was possible to venture out and shop for themselves, cocooners have often chosen to do so, preferring some risk in order to express their autonomy. At this particular moment, when the lines between safe and unsafe, lockdown or openness are blurred, older people hover between social categories that fluctuate between the vulnerable margins or the robust mainstream. When there is a lack of clarity over what is safe or not, it is worth remembering that efforts to keep groups safe not only impinge on their physical wellbeing but may also work to pigeonhole and marginalise them in unanticipated ways. Lockdown practices are not only rationalised actions but are saturated with sentiment and often conflicted.

[i] Watterson, J. 11/05/20 ‘Tennis courts to remain off limits for over-70s after May 18th for health reasons’. The Irish Times, available online https://www.irishtimes.com/sport/other-sports/tennis-courts-to-remain-off-limits-for-over-70s-after-may-18th-for-health-reasons-1.4250613, accedes 11/05/20.

[ii] For example see Garvey, P and D. Miller (forthcoming) Ageing with Smartphones in Ireland: When Life Comes Craft. UCL Press.

[iii] Mintz, S. W., & Du Bois, C. M. (2002). The anthropology of food and eating. Annual review of anthropology, 31(1), 99-119

Close

Close