Information and mis/disinformation during the pandemic in Milan

By Shireen Walton, on 3 July 2020

During the spring of 2020, when the COVID-19 crisis was at its peak in Italy, I observed through my research participants and friends in Milan how information sharing, and particularly health and care information – from government and regional levels, through to community and family – was embracing digital and visual avenues of communication to significant and creative extents.

Figure 1: Image shared in a community WhatsApp group in NoLo at Easter. Source unknown.

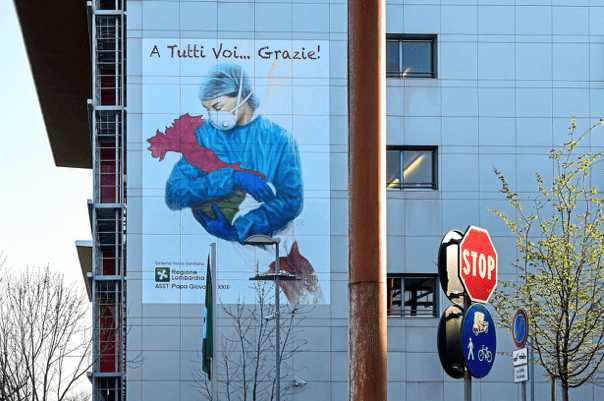

Amid the broad range of sharing practices were many documents, advertisements, and images aimed to raise community awareness about health, safety, and wellbeing, as well as digital accessibility. For example, in March 2020, an awareness initiative administered by a local NGO dedicated to the needs of families and children in the neighbourhood called on neighbours to share their wireless connections within apartment blocks to assist children whose families do not have internet connections at home to be able to follow school lessons online. Often such campaigns are also translated by NGO groups into languages spoken in the area such as Arabic and Spanish, in order to reach broader members of the community.

Figure 2: Example of a local NGO campaign to assist with families during lockdown in Milan by calling on neighbours within apartment blocks to share wireless connections with those without WiFi.

These kinds of initiatives led by NGOs in Milan during quarantine were also met with programmes of ‘digital solidarity’ to assist with digital connectivity during the lockdown. Here, the Italian Ministry for Technological Innovation and Digitization partnered with private companies to offer forms of assistance to citizens such as free online newspapers, faster internet, access to online education and entertainment platforms during the lockdown. Furthermore, the Ministry of Health created a series of infographics about protocols to help prevent the spread of the Coronavirus, many of which were widely circulated via WhatsApp and Facebook.

Amid the rapid spread of both the virus and information during the pandemic, unverifiable information also spread quickly across the community, the country, and the world via memes, short videos, and text/voice messages. By March, the Italian state increased its involvement in this issue with an attempt to communicate the facts about the virus, with a significant pushback by Italian medical authorities against ‘fake health information’ that was circulating via WhatsApp. The Italian Ministry of Health soon published a list of ten particularly pertinent ‘fake news’[1] items about the Coronavirus that had been identified within the Italian social web, from the myth that drinking tap water was dangerous to health to the rumour that wearing face masks in the home would help limit contagion, to the idea that taking a hot bath would kill off the virus.

Figure 3:Screen shot of the Italian Ministry of Health website section on Coronavirus and Fake News. Image Source: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=4380

In a widely circulated YouTube video appeal Roberto Fumagalli, a senior Medical Director from Milan’s Niguarda hospital, pleaded to people in Milan, and to the nation, to stop circulating unverified information and gossip about Coronavirus, including a stream of official-sounding voice messages that had been sent via WhatsApp to people across Italy about what doctors are/are not doing or who they are/are not treating.

In light of false and misleading information concerning the virus, and in the context of high anxiety and stress caused by the experience of quarantine, a number of research participants in NoLo had intervened on social media, asking for people to stop sharing unverifiable facts and misinformation that were proving inflammatory and divisive – a practice of regulation and control of the social web that I had witnessed more broadly in the community in the previous two years during fieldwork in Milan.

Figure 4: Daily news and chats in Milan. Photo taken by author.

The spread of misinformation, or unverified or false information via smartphones and social media remains a significant part of public conversation in Italy, as in other parts of the world. This issue is particularly seen to affect older populations and is a priority concern and main point of focus within ageing policy discussions, with the assumption that older people are particularly vulnerable to ‘fake news’.

Figure 5: ‘Anziani e Fake News’ (Elders and Fake News). Advert for a discussion event on ‘information and disinformation in the era of social media’) organised by AUSER, a main nation-wide ageing NGO in Italy. https://www.auser.it/comunicati-stampa/anziani-e-fake-news-come-non-cadere-negli-inganni/

My broader research encountered concerns amongst middle-aged and older adults about the role of smartphones in spreading unverified information quickly and easily in today’s world, while a number of research participants also recognised that dis/mis information[2] also has historical roots, reflecting uses of sectors of the media and television to misinform and/or mislead, citing examples from the media and television era of Berlusconi in the 1980s to the propaganda of the fascist era in the 1930s, which many of them and/or their parents had also lived through.

Overall, the multifaceted and deep-rooted issue of contemporary information and mis/dis-information in Milan, amidst and beyond the pandemic, highlights a range of contemporary tensions and paradoxes concerning social and public life within the present information age, which smartphones – as products of, and companions to the current age – are complexly implicated in.

[1] ‘Fake news’ is a significant feature of media coverage and popular conversation in Italy. The Collins English Dictionary defines fake news as the ‘false, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting’: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/fake-news

[2] The distinction between misinformation and disinformation has been defined in terms of intentionality. The former describes the sharing of information regardless of intention, while the latter involves the intention to mislead, misinform and/or manipulate. See: https://www.dictionary.com/e/misinformation-vs-disinformation-get-informed-on-the-difference/ and https://en.unesco.org/fightfakenews

Close

Close