Coronavirus in Japan: smartphones and keeping self-informed

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 17 April 2020

“I am ashamed of our government” messaged Inoue san*, a 65 year old woman from Osaka. She is retired and has been staying at home as much as possible during the coronavirus outbreak. “In Japan, regretfully it seems that people don’t think it’s so serious. I can’t believe it!” For the past month my friends in Japan have been telling me that they are concerned by the slow response to the coronavirus from the Japanese government.

For many people I got to know, it is customary to go to the clinic or even hospital as soon as you suspect you may have the flu. According to my doctor contacts in Kyoto, hospitals are starting to become overwhelmed by the numbers of people seeking help and advice. As the story of Sato san shows, illustrated above, even the official corona virus hotline recommends for people to go to hospital. There is a feeling that unless drastic measures are taken, such as a lockdown, the number of infections will soon explode and hospitals will not be able to cope.

While here in the U.K. the numbers of cases and fatalities rose dramatically during March and early April, in Japan the number of confirmed cases remained low and is only just reported to be rising. While some of my contacts believe that the government’s response has therefore been appropriate, in general trust in the government’s crisis response is low among the 60 or so individuals I got to know well during my fieldwork. This negativity is primarily due to their concern over how the government handled the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Japanese media is largely state-controlled and many people question the transparency of reporting. During the coronavirus pandemic people are turning to their smartphones to seek out the latest information about the virus, such as through the messaging app LINE which collates news from various sources.

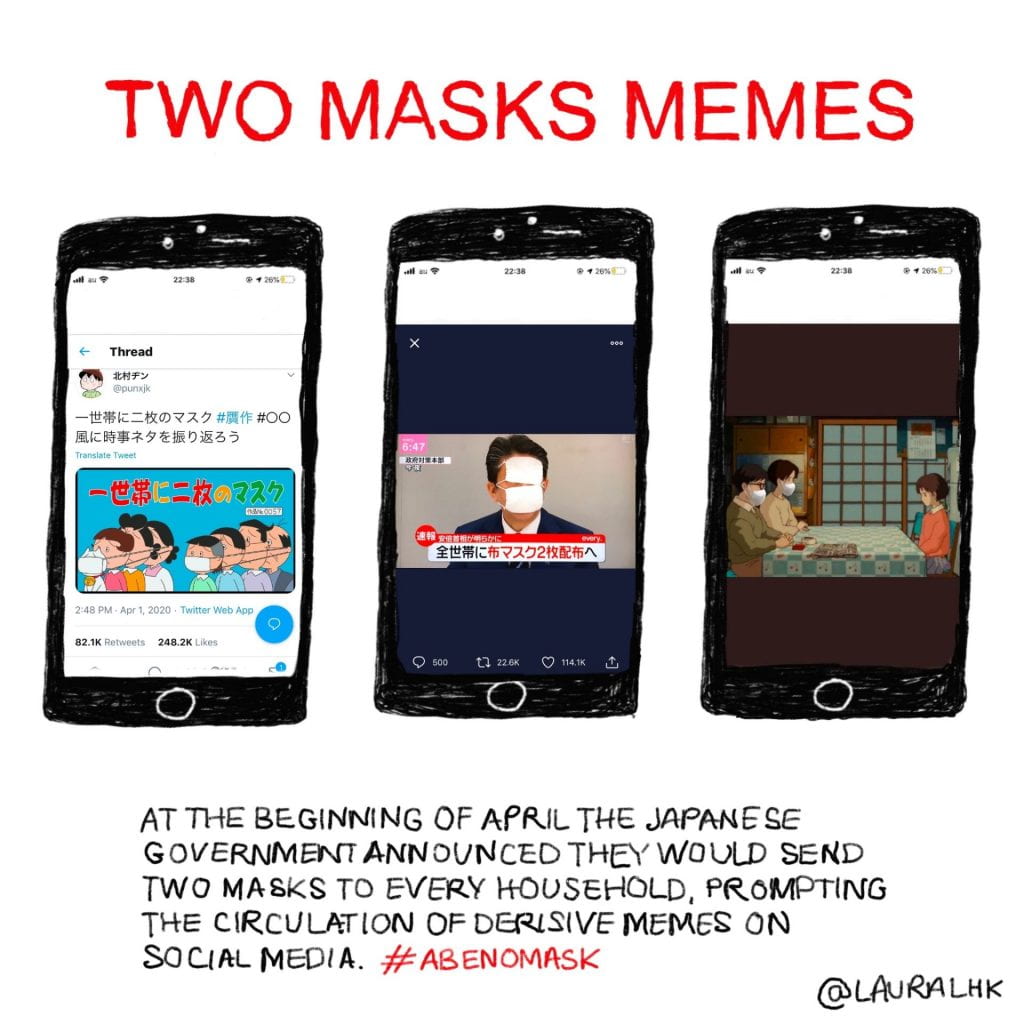

The smartphone is not only a key source of news, but it is also where people can express their frustration with the government’s response. What many people want is for employers to be forced to close businesses, and for there to be financial aid given to workers. For example on 16 April there was an organised Twitter protest targeting government policy, with the hashtag #休業補償と一律給付で命を守って, meaning ‘save lives with leave compensation and uniform benefits”. While Japan’s working poor continue with their daily commutes to work, the government have promised to send face masks to every household. This gesture has been widely regarded as out of touch with reality, and has prompted ridicule online, such as the memes below and the trending hashtag #Abenomask which plays on Prime Minister Abe’s eponymous ‘Abenomics’ economic policies.

On 16 April the government issued a nation-wide state of emergency, giving them greater power to request the closure of businesses. The Japanese constitution makes it difficult for the government to issue the sort of lockdowns that we have seen in Europe, so they have relied on issuing requests for people to work from home if possible and avoid mass gatherings. Yet these guidelines have not been binding by law, meaning that many employers have largely been carrying on as normal, while individuals feel increasingly conflicted.

On 16 April the government issued a nation-wide state of emergency, giving them greater power to request the closure of businesses. The Japanese constitution makes it difficult for the government to issue the sort of lockdowns that we have seen in Europe, so they have relied on issuing requests for people to work from home if possible and avoid mass gatherings. Yet these guidelines have not been binding by law, meaning that many employers have largely been carrying on as normal, while individuals feel increasingly conflicted.

See Laura’s Instagram for more illustrated ethnography.

*Names have been changed for anonymity in this blog post.

Close

Close