How to find a smartphone in Yaoundé

By p.awondo, on 14 February 2020

I arrived in Yaoundé on the evening of the 5th of February 2018. The next day, I went to a café in the city centre known to be one of the few that only serves local coffee and local sandwiches, with an emphasis on the ‘local’ label. For example, the café serves a ‘mboa burger’. The ‘mboa’, a term that comes from the Douala language (one of 170 recognised national languages), means ‘the country’ or ‘the land’. They also serve a ‘bissap’ juice and a ‘Foumban chicken sandwich’, the latter named after a city in the Western region of Cameroon from which the coffee served in the café originates. Foumban is also a city that is highly regarded for its agriculture and livestock.

I watched the street from inside the café. The street below is called ‘Anne-rouge climb’. It’s a pretty busy street, with shops on both sides selling clothes imported from China and Turkey. There is also stationery, micro-finance establishments and telephone shops. Here and there, ‘telephone credit’ sellers are sheltered under mobile phone operator-branded umbrellas, each one a different colour. The umbrellas that represent the South African operator MTN are yellow, the ones that represent the French operator Orange are (unsurprisingly) orange, while the local operator Camtel has blue umbrellas. Throughout the city, we find these colour codes wherever a credit seller (locally called a “call box”) sells credit, even if the seller is selling credit from several operators at the same time.

Different mobile phone operators’ colours in Yaoundé. Knowing that the “call-boxes” also sell other products as I myself am Cameroonian, I asked a coffee server if one of the sellers on the street below had SIM cards for sale. He answered yes. Having finished my coffee, I approached the first “call-box” asking whether they had SIM cards.

“Do you want an Orange or an MTN card?” the seller asks.

“Whatever”, I said, “I just want a SIM card”.

A few minutes later, I had a new SIM card.

“If you want an Android phone, you just have to go down the street. Below, you will come across Kennedy Avenue. There are shops and phone sellers all over there. Whatever type of phone you want, you will find it there.”, he added.

The seller had anticipated that I would then immediately ask where I could quickly find a phone. In Yaoundé, and in the rest of the country, the “Android” phone (that is to say a phone equipped with the Android operating system), is the expression which is equivalent to the word smartphone. So if you ask a Yaoundean whether he or she has a smartphone, he or she will not answer you or will ask what a smartphone is, but if you refer to “an Android phone” they will immediately answer, quickly listing the different brands of Android phones.

I went down the “Anne-rouge climb” in the direction of Kennedy Avenue, following the instructions of the “call-boxer”, and then stopped at the crossroads of this very famous street of Yaoundé. The avenue is famous for its trade activity, which is mainly oriented towards the trade of computer products and smartphones. Here and there, on the pavement, a wide variety of items are on display. These are mainly products of Asian origin. Among these shopping streets, many young men in their late 20s or early 30s seem to be the main ‘players’ in this market. Hundreds of people come and go, and these young men challenge, hold your hand if necessary, offering you many products to choose from. There are smartphones of all brands; from the best known ones (iPhones, Samsungs, Huaiweis, Tecno, LG) to the least known, more obscure brands.

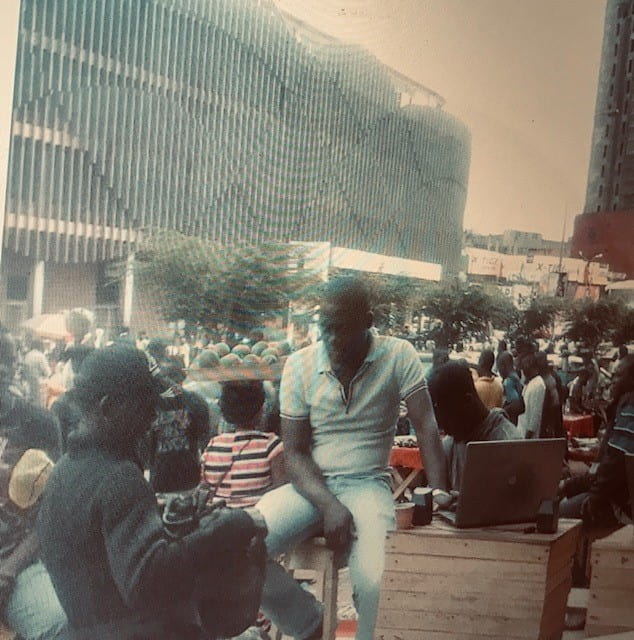

Man selling phone credit in Yaoundé. The South African mobile phone operator MTN is represented here by the yellow umbrella. Photo by Patrick Awondo (CC BY)

Some of the young traders have also got clothes on offer – everything from jeans and sports shoes to ‘city shoes’, costumes, shirts. Others have got chains and watches for sale. To promote their products, they present them as valuable items that only ‘travellers’ (voyageurs) know about. The category of the ‘voyageur’ is a category which in this context underline the fashionable dimension of the products , as well as their quality. If the traders treat you as a ‘voyageur’, they are trying to underline the quality of your clothes as much as the expectations linked to this status and its appearance. The ‘voyageur’ is demanding with regards to quality, which he or she supposedly knows about because he comes from Europe or elsewhere, but also because he is able to pay. The category is not in the least related to travel – it is a characteristic that one is supposed to reflect, as well as a commercial category, one that works to flatter the customer and raise the trader’s chances of getting a ‘higher bid’, as it were.

A young man calls me and asks me if I want a ‘real phone’. He emphasises that those offered on the street are for the ‘little ones’.

‘You are a big man, come and I sell you the real options’, he says.

By this, he means that the backyard and in the small, cramped shops that are in the small corridors of the avenue, is where the ‘real’, original products are. He adds : ‘Outside, it is the “bulk products” that people are selling. Since you haven’t found anything, because I’ve been watching you for a while, that means you’re looking for options. So I’m showing you a real phone with options.’

A few minutes later, we cross the street, followed by children who asked us if we could spare any change. In the dark corridors of a quite unsanitary-looking building, we arrived at a small shop where second-hand laptops of all brands were stored, as well as second-hand phones and a few USB drives, computer chargers, central units and discs. The young man introduced me to the seller, stressing that I am looking for an ‘option’. The seller, a man in his forties, took out 4 smartphones from under his small counter – two iPhones (a 6 and a 7), one Samsung Galaxy and a latest generation Motorola phone. ‘Voyageur, since you want the options, here’s what we have … but if they are not good, I can call for something else. We have everything here, but across several stores.’, he says.

After paying 80,000 XOF (around €122), I came out with a used iPhone 6 that I quickly tried to test by introducing the SIM card I had bought at the call box earlier. It should be noted that in this business, there is no guarantee. The only real guarantee is often to establish a relationship with the seller and locate him and his partners in order to be able to return in the event of a problem.

What I have just described is a mundane scene from the city of Yaoundé. Kennedy Avenue is the centre of the life and traffic of the smartphone and the telephone more generally. People who want to buy a smartphone, whether new or used, would first go to this part of the city. It is a place recognised for the possibilities it offers, located in the heart of the downtown shopping district and considered locally to be the heart of “telephone culture” and digital life.

Below is a short video showing the phones that might be on offer in one of Yaoundé’s mobile phone shops:

Close

Close