Doing time — by Pauline Garvey

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 5 March 2019

This month I have been asking people about retirement. I’m finding that some people adopt grand projects on their retirement: one man, for instance, published a book that compiled all his photographic works completed over 12 months in the 1950s. A woman told me that she has collected all the short stories and opinion pieces she ever wrote and put them in a folder for relatives to read after she is gone.

Finally, one man who does not see himself as particularly artistic or creative, keeps a photographic record of his holidays to leave to his adult children in years to come. As we talk about such matters, the word legacy comes to mind. But legacy is difficult to capture because for many – including myself – it is unclear precisely what this term means. For some it concerns completing something that has worth and would otherwise remain undone. For others, it means leaving a sort of cartography of memories behind for the next generation.

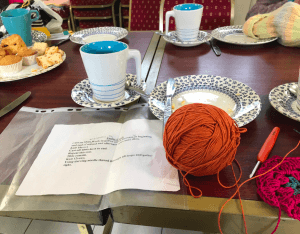

Legacy, I have realised, tends to suggest individualised works and occasionally my assumptions have been challenged in this regard. This month, a group of retired, elderly women I meet regularly embarked on a craft project to knit several hundred small chicken shapes in preparation for Easter. The chicken shapes will be given eyes and ribbons around their necks. They will be stuffed and decorated. The local chocolate factory have agreed to donate several hundred small chocolate eggs that will be inserted into the chickens and then the totality will be given to the local hospice as part of their fundraising activities.

As I’m told of these tasks, I marvel at the work, the energy, the organisation and the generosity of these women and wonder if activities such as these represent a collective legacy, something bigger than the sum of its parts. But at the same time, I think there is more to these activities than issues of legacy. Keeping busy is a common motif in my research. One man described his wife as ‘she’s like a shark, they die if they stop moving’ whereas another referred to the bonus of ‘having something to get me out of bed in the morning’.

Anthropologists are aware that it is in the structured routines of the day, that time is felt and experienced. As my research progresses I find that respondents constantly talk of practices in terms of time, ie. finding something that gives shape to the day, that takes time and converts it into something productive.

Time, for some becomes problematic not because it is scarce but because it must be filled.

Commonly women in my craft group, aged in their 70s and 80s comment on their need to stay busy. One woman told me she had knitted 100 small chickens because ‘I just knit when I’m watching tv’. Another joined in that she also likes to have something to do when watching television, ‘I feel guilty if I’m not keeping active’, she said.

Of course watching television is not ‘doing nothing’, but the emphasis is on being productive with time, not letting is slip away. This point is considered so self evident that some informants look at me askance when I ask why it is a good thing to be active.

Activities fulfil the purpose of keeping them busy, of filling time that otherwise might be empty where they might feel adrift. In that respect, time is something that is ideally practiced. Which leads me to wonder: which is most important – the doing of time or the activity that fills it?

Close

Close