NCDs in the time of Covid: documenting the social drivers of our wellbeing

By charlotte.hawkins.17, on 14 August 2020

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, diabetes, strokes, cancer and depression disproportionately affect people in low-income contexts, particularly as they get older. They can be some of the most resource-intensive conditions to manage, requiring changes in working routines, regular visits for hospital care and long-term medication. Chronic, long-term illness in old age can be particularly demanding for family caregivers as they navigate hospitals and home life. Yet they are also often overlooked in terms of research, policy and funding. In Uganda, for example, it was only in 2005 that NCDs were given an explicit place in the national health strategy, and there remains limited research and resources, particularly for long-term funding to support NCD information, prevention and care[i]. The relatively recent rise of NCDs as widespread health problems in Uganda is often attributed to contemporary lifestyles, the pollution and stressors of city life and personal problems imposed by global processes[ii]. As much as biological factors, NCDs can be inextricably linked to inequities around employment, education, nutrition and housing. Wide-reaching economic factors influence both experiences of chronic illnesses and access to treatment, determining who is responsible for long-term care; often families, navigating overstretched health systems and existing obligations.

Anthropology has a lot to offer in understanding how people manage uncertainty related to long-term illness. As argued in my previous blog post, it is often through dialogue and conversation with each other, that people seek to establish control in an ambiguous world[iii]. By detailing conversations around chronic illness and care, we can gain an insight into how people also understand and manage the wider world, particularly in terms of how health inequities impact on their everyday lives. The pertinence of this anthropological project, to take pre-existing conditions, their conceptualisation and management, into account, has been highlighted by the current COVID-19 pandemic, which has shown that the epidemiological boundaries between communicable and non-communicable diseases are evidently blurred, with both determined by social networks and inequities[iv]. Intensified pressures on households, health workers and hospital administrators who have to improvise and make do have shown the need for preparedness through prior and ongoing understanding of the “complex social drivers of our wellbeing”[v]. And clearly, ways of navigating stratified access to health provisions are of primary importance not just to those obstructed, but to us all.

Pharmacy service inside a regional government hospital near the Kampala fieldsite

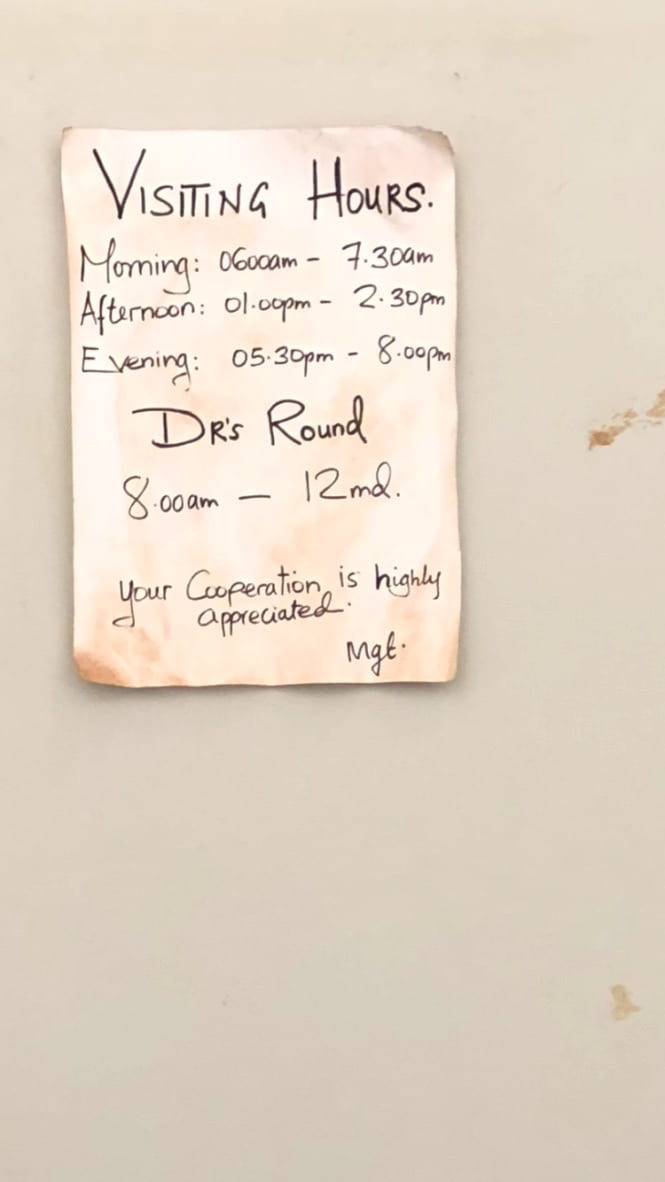

Notice for visiting hours and Doctor’s round at the hospital

[i] Susan Reynolds Whyte, ‘Knowing Hypertension and Diabetes: Conditions of Treatability in Uganda’, Health & Place 39 (May 2016): 219–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.07.002.

[ii] David Reubi, Clare Herrick, and Tim Brown, ‘The Politics of Non-Communicable Diseases in the Global South’, Health & Place 39 (May 2016): 179–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.09.001.

[iii] Susan Reynolds Whyte, Questioning Misfortune: The Pragmatics of Uncertainty in Eastern Uganda, Cambridge Studies in Medical Anthropology 4 (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[iv] Lenore Manderson and Ayo Wahlberg, ‘Chronic Living in a Communicable World’, Medical Anthropology 39, no. 5 (3 July 2020): 428–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1761352.

[v] Napier, D. (2020) The Culture of Health and Sickness: how Uganda leads on Covid-19. In Le Monde Diplomatique p.6-7

Close

Close