Empty nesters and ‘under-occupied’ homes — by Pauline Garvey

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 14 October 2018

Quinn, David 17/04/15, If grandparents went on strike, we would all be sunk, The Irish Independent, available electronically as https://www.independent.ie/opinion/if-grandparents-went-on-strike-we-would-all-be-sunk-31149507.html

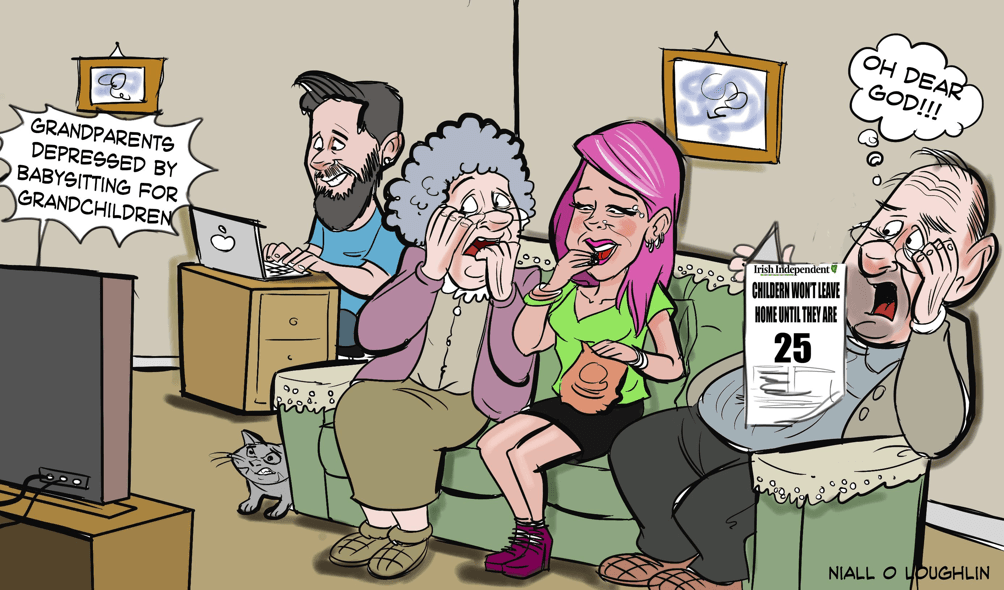

Amongst the proposals for the recent Irish budget 2018, government ministers looked to the grey vote and weighed up options for a grandparent grant, reported on in the media as the ‘granny grant’. The idea was advocated by Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, Shane Ross, who calculated that 70,000 grandparents could be eligible for the grant, costing the state €71 million a year. The proposal was based on the widespread recognition that grandparents undertake a substantial burden in a country where childcare is exorbitantly expensive and state subsidies limited. Many young couples turn to their retired parents to look after their offspring, and these grandparents undertake their labour often in their own homes. A study from 2015 found that 60% of grandparents looked after their grandchildren once a month, while one in five looked after them more than 60 hours per month.

At the same moment as talks of the granny grant circulated however, the same minister argued in favour of introducing a ‘granny-flat grant’ in order to encourage older people to transform the upper floors of their houses and rent them to lodgers, thus contributing to the housing pool and giving elderly householders a source of income. Piloted in one house in north Dublin, the granny-flat grant is far more controversial among people I meet in the course of my fieldwork.

One woman complained that it is seemingly fine for grandparents to bear the brunt of childcare but somehow their undisputed rights to their own home is cast in doubt. As she said ‘my parents worked their whole lives and paid tax, as did I. I inherited this house and paid for its upkeep from my wages since I started working fifty years ago. But now “the boys” are talking of taking my first floor?’

Another woman commented that the logistics of building a kitchen and finding a suitable tenant seemed a daunting task. While a third pointed out that ‘no one expects a 40-year old singleton in a 3-bedroom house to downsize, so why should I?’ In media reports there is no sign that the search for ‘under-occupied’ houses includes all spacious residences in the state, but instead focuses squarely on the homes of the elderly, and occasionally those in social housing. One question that this prompts is why does the idea of under-occupied housing seem to apply only to the elderly, leading some of my research respondents to feel that their right to their own homes diminishes with every passing decade?

Close

Close