Dr. Google will see you….anytime.

By Daniel Miller, on 4 October 2018

Given that I suspect almost everyone you know at least occasionally uses google to look up health related information, at least sometimes, there is not a great deal of research on the consequences – though I have no access to google’s own research. This has therefore been a major focus of my work on digital technologies and health here in Ireland. What are the main conclusions so far?

Given that I suspect almost everyone you know at least occasionally uses google to look up health related information, at least sometimes, there is not a great deal of research on the consequences – though I have no access to google’s own research. This has therefore been a major focus of my work on digital technologies and health here in Ireland. What are the main conclusions so far?

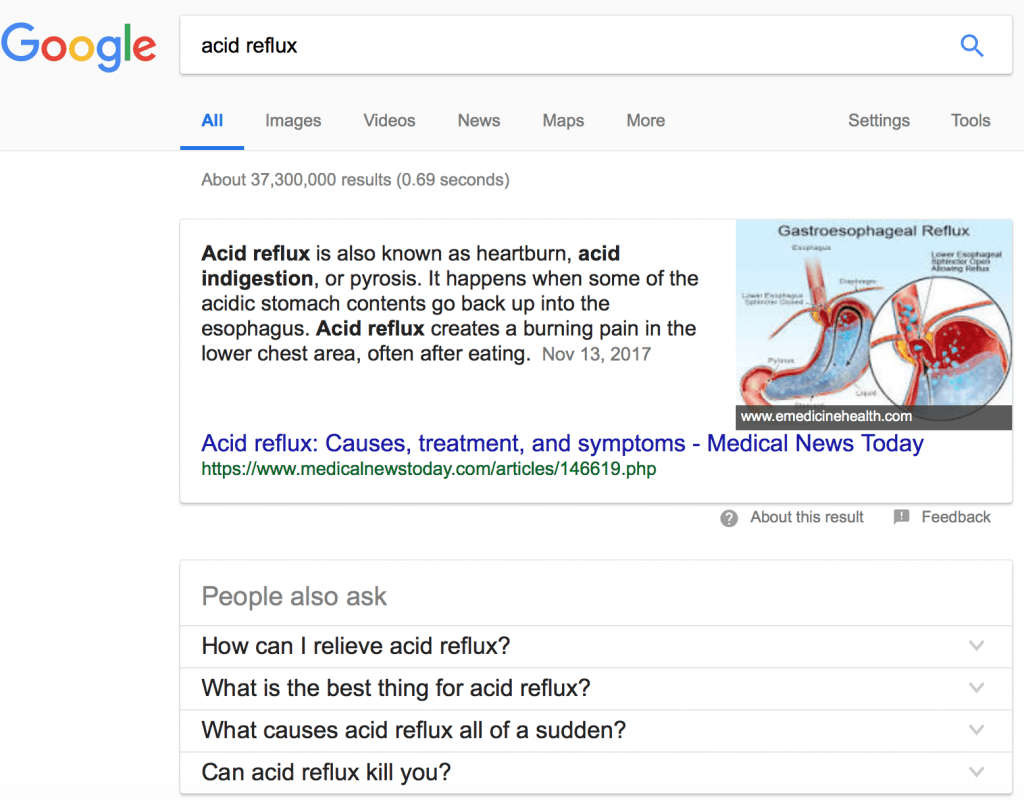

Most noticeable is the way googling exacerbates differences in class and educational background. There is a pronounced spectrum. At one end are those, often without medical backgrounds, who would comfortably use google to track down the latest medical journals, because they are trained in research. At the other end are those who simply look at the items that come at the top of their google search, which are often scare stories, rumours or commercial sites. As one pharmacist noted `They just type it into google and probably read the first couple of articles that come up. So whatever’s most recent. They don’t differentiate NHS from random.’ This can be very frustrating to medical practitioners when it leads to their patients locating the problem in the latest online speculation, rather than starting with the practitioner’s own analysis.

This spectrum is complex because of several contradictory factors. A surprising number of people in this town mention that there is someone with medical training, within their extended family, who may mediate their searches. There is also a well educated section who use googling as a kind of anti-medical-establishment resource seeking out alternative and complementary treatments, which they feel deal with issues and consequences that are neglected by bio-medical establishments.

At both ends of the spectrum most people see equally strong positive and negative consequences of googling. They feel more knowledgeable, and in control of their treatment, but they also see googling as a cause of considerable stress and anxiety. They note that pretty much any symptom could potentially indicate cancer or some other life threatening condition. Some therefore limit their googling. Many people are wary of informing doctors of their searches for fear they will be seen as a nuisance or a challenge to the doctor’s authority. Googling may be a factor in deciding whether to see a doctor, but it also employed subsequent to visits to the doctor in order to better understand terminology, medicines and procedures. Pharmacists may actively guide people in their googling. Those who differentiate trusted sources of information mostly choose the US Mayo clinic or the UK NHS site rather than any Irish sites, and also favour specialist sites dedicated to their particular conditions. Unlike early evidence from other fieldsites in our project, such as in our recent blog post about Cameroon, there is little use of YouTube here for health information.

To conclude, google appears to provide equal information to all, but in practice, it may extend class and educational differences and create problems of online health literacy. Well-educated people become still better informed, while poorly educated people are left even more confused and anxious. The obvious solution is kite-marking those sites backed by established professional bodies. This does nothing to prevent a preference for complementary health sources, but does ensure a more equal playing field for those who, to use a common expression here, think of online as Dr. Google.

Close

Close