UCL Student Recruitment: International Visits Schedule 2019/20

By By Guest Blogger, on 27 September 2019

International competition for overseas students has never been fiercer, with recent reports showing that the UK’s main competitors are increasing their international student numbers faster than the UK and eating into our share of the global market. Prospective students will use many different sources of information to whittle down their choices, but the opportunity to speak with representatives in person is still highly valued by all those who have the opportunity to meet us, and still forms a key element of the international student recruitment strategy.

International competition for overseas students has never been fiercer, with recent reports showing that the UK’s main competitors are increasing their international student numbers faster than the UK and eating into our share of the global market. Prospective students will use many different sources of information to whittle down their choices, but the opportunity to speak with representatives in person is still highly valued by all those who have the opportunity to meet us, and still forms a key element of the international student recruitment strategy.

Each year during the planning phase, the student recruitment team will assess what worked well in the previous year and what can be improved and revamped from our trip schedule. We approached this year with a new tactic, using a matrix to tier countries based on size of market and potential for recruitment to UCL programmes. Based on these results we have invested more in markets with the greatest potential at the same time maintaining a presence in lower-tiered markets in order to diversify the student body. We noticed that applications from certain markets were growing yet conversion from offer to enrolment could be improved. For this reason, we have shifted away in some markets from mainly application generating trips in the fall to be more focused on conversion activity in the spring. We have added conversion trips to the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. We will be monitoring the application, offer and acceptance numbers for each market against activity within that market to evaluate the success of the additional conversion activity.

Details of UCL’s international student recruitment activity for 2019/20 are now available in the UCL Visits You section of the international pages of the UCL website. The event list is regularly updated as we add more details about forthcoming events, so bookmark the site and check it regularly for the latest information. Members of the Student Recruitment team will represent UCL, and academic staff and other departmental representatives will join us at selected events. Each overseas trip includes a range of activities such as attendance at an education exhibition, university visits, school visits and meetings with key contacts in-country, such as funding bodies and alumni. Each trip aims to include a mix of events to cover all levels of study.

The 2019/20 recruitment activity is scheduled to include visits to a wide range of countries, covering every continent except for Antarctica. Most of the countries on the list are places we visit regularly. It is important for us to be constantly reviewing our activity, and we must be both alive to new opportunities and bold enough to change what we do not feel is working. The education sector welcomed the government announcing that international students will be allowed to stay in the UK for two years after graduation to find a job, reversing the decision made in 2012 by then Home Secretary Theresa May. We anticipate this will generate an influx of applications, especially from India the market that saw the largest decline in students coming to the UK when the scheme was pulled in 2012. The additional trip added to India in the spring is timed very well to not only focus on conversion but also address the new visa scheme.

All the trips are thoroughly researched beforehand and analysed afterwards, to ensure that we are participating in the most appropriate events and reaching as wide an audience as possible. Overseas visits also provide the Student Recruitment staff with invaluable opportunities to meet key contacts and influencers, as well as to get the latest market information. If you would like to know more about any of our overseas recruitment events, please contact Katja Lamping, Director of Student Recruitment at k.lamping@ucl.ac.uk .

Ask an Academic: Dr Taku Fujiyama, Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Transport Studies

By By Guest Blogger, on 25 September 2019

Dr Taku Fujiyama is Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Transport Studies (UCL Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering).

Dr Taku Fujiyama is Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Transport Studies (UCL Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering).

Taku has been collaborating on the development of models and algorithms for real-time railway traffic optimisation with academics from Roma Tre University.

In this edition of Ask an Academic, he tells us more about this collaboration and how he has been working to encourage collaboration between the academia and the railway industry.

Q: Can you give us a brief overview of your research project?

A: Prof Andrea D’Ariano of Roma Tre University and I have been collaborating on the development of models and algorithms for real-time railway traffic optimisation for several years now.

Real-time railway traffic control is essential for railway operations in major cities such as Rome and London where many trains are running, and delays often happen. In this City Partnership-funded project, we ran short courses and workshops on algorithms at both Rome and London to facilitate further collaboration between the academia and the railway industry.

Q: What got you interested in the subject in the first place?

A: Before joining UCL as a PhD student, I was working in a railway company in Japan where I was involved in major station development projects in Tokyo, where I designed passenger facilities (platforms, subways, and concourses). They are still there, and hopefully will be there for some time. So I was already involved in this subject when I started my PhD.

Q: How did the collaboration with Roma Tre come about?

A: Andrea and I have been in discussion to do something together since we first met. Academics are always looking for opportunities, and luckily this City Partnership gave us an opportunity. Later our common collaborator Dr Yihui Wang (Beijing Jiaotong University) joined this, so it is now a Rome and Beijing partnership for UCL.

Q: What difference do you hope this project will make?

A: This project may be different from other projects funded by the scheme. Andrea, Yihui and I would like to not only advance research collaboration but also involve more industry partners. Whilst I am already collaborating with industry partners, this project allows Andrea, Yihui and myself to increase dimensions of our academic capabilities so that we can address complex multi-dimensional issues which our industry partners face.

Q: What has been the most interesting outcome from your work with Prof Andrea Ariano?

A: As an immediate output from the project, we delivered a short course which attracted more than 80 participants – some practitioners were even from other countries including the USA. Whilst we are working on some academic papers based on discussions between ourselves, we are also hoping that we can convert our practitioner networks to some platform which harvests academia-industry collaboration.

Q: What would you say to other academics at UCL thinking of applying for Cities partnerships Programme funding?

A: This is a unique and helpful initiative, which enables any collaboration to go further. If you are lucky to have a partner in a selected city, just go for it! (And I hope that this programme will include more cities.)

UCL Qatar: Introducing Innovation Labs to Zambian Cultural Heritage Institutions

By By Guest Blogger, on 25 September 2019

By Milena Dobreva-McPherson, Associate Professor, Library and Information Studies, UCL Qatar.

Over the years, UCL academics have contributed in different ways to the six Grand Challenges. One of them is Cultural Understanding, and it looks at the differing, complex, and evolving relationships between people, communities, and culture in the interconnected world of today.

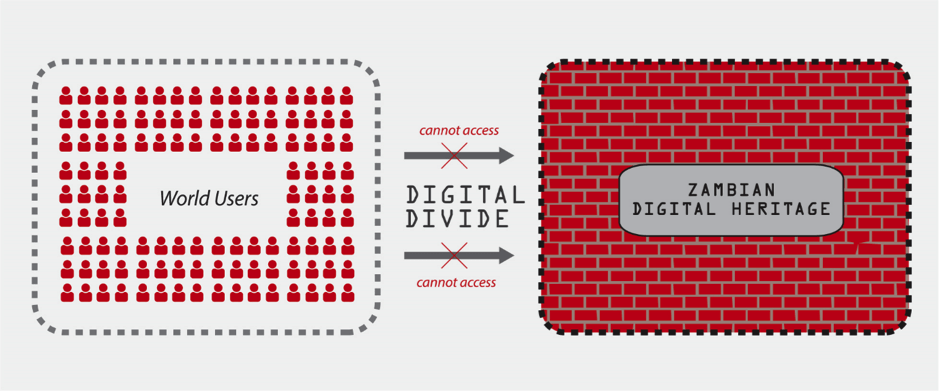

After many years of digitisation in libraries, museums and archives around the globe, there is a vast accumulation of digital content. We are used to it at our fingertips on any digital device. But imagine that you are interested in the diaries and other objects related to the explorations of David Livingstone in Zambia. They have already been digitised, but you must take a trip to consult the digitised collection of the museum on-site because it is not available online.

This is still the case with plenty of cultural and scientific heritage digital content from the Global South, a region which suffers the digital divide.

The digital divide results in many deficits in access to knowledge due to missing, or the very slow adoption of, modern technology. In the cultural heritage domain, the digital divide results in the lack of exposure of digital content which exists but is not made available online. There are various explanations why this is the case – ranging from lack of suitable infrastructure for digital asset management to inadequate or missing policies for user engagement with the digital content.

Led by the desire to explore what this means in the Sub Saharan African context, I submitted a proposal to the most recent call for teaching activities in Africa and the Middle East of the Global Engagement Office at UCL. It aimed to deliver the first workshop in innovation labs in cultural heritage institutions for Sub Saharan Africa in Zambia.

Having two major obstacles in mind – inadequate infrastructures and lack of user engagement policies – we designed a workshop which addressed both areas. In a world where Open Science becomes increasingly popular, the opportunities for digital presence are changing. One solution to the issue of not sharing content online due to inadequate institutional infrastructure is to start using open platforms.

The exciting work started when my proposal received support, and we scheduled our workshop to be delivered on 1 August 2019 at Livingstone Museum, Zambia.

Fig. 1. Zambian digital content is mostly available for consultation in-house – thus world users cannot access it as a consequence of the digital divide

Fig. 1. Zambian digital content is mostly available for consultation in-house – thus world users cannot access it as a consequence of the digital divide

The rationale of the workshop was to spread the innovative knowledge accumulated at UCL Qatar to setting up successful innovation labs in cultural heritage institutions in Zambia. The workshop targeted professionals from Cultural Heritage Institutions who have responsibilities to manage digital collections and those with future intentions of engaging in the curation of a digital collection in Zambia. The workshop aimed to:

- Equip museum and library professionals in Zambia with knowledge on the approaches to setting innovation labs and discussing how local institutions can work towards creating such labs.

- Raise awareness on the role cultural institutions offering digital content play in boosting the digital skills of scholars, educators, learners, and creatives.

UCL Qatar worked with several institutions in Zambia to prepare and deliver the workshop, including the National Museums Board of Zambia – an umbrella institution for national museums, the National Archives of Zambia, and the Department of Library and Information Science from the University of Zambia (UNZA). It also included online interventions from the British Library.

We focused the content of the workshop on state-of-the-art digitisation, examples of digitisation projects from Zambia, and setting up innovation labs in libraries, museums, and archives. There was also plenty of discussions and a practical exercise on understanding better the needs of users of digital collections.

Participants

Initially designed for 15 participants, the workshop was delivered to a total of 27 participants (see Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Profiles of participants

Fig. 2. Profiles of participants

Figure 3: Workshop participants

Figure 3: Workshop participants

Feedback and impact

Eighteen out of the 27 participants provided feedback and it was overwhelmingly positive. The participants were asked to rate the content of the workshop and also to comment on the value of the knowledge for themselves and their institutions.

One participant said:

“The programme should be repeated for other professionals in Zambia and if it comes I will recommend it to others.”

There were also opinions on how to take forward the knowledge shared at the workshop:

“Put the knowledge acquired in the workshop to use ASAP, conduct a follow up workshop to determine progress in created innovation labs, and massive awareness creation of the existence of the innovation labs created to potential users”

“Embrace new trends and technologies relating to digital platforms and information sharing through innovation labs”

“I’m suggesting that maybe if its possible to continue having such workshops every year so that we learn more new techniques on how to improve our libraries. Also, the workshop should have taken at least three days to allow participants learn more”.

The workshop received media coverage from three newspapers and some local radio stations.

Another innovative outcome from this event was that UCL Qatar added the first-ever dataset of the potential for Innovation labs in Africa on the UCL repository: Dobreva, M., and Phiri, F.. (2019, August 20). Cultural Heritage Innovation Labs in Africa (Version 1). figshare. https://doi.org/10.5522/04/9685127.v1

A Google folder with all the presentations, press coverage, and photos of the event is also openly available: Innovation Labs Workshop – Zambia

Conclusion

The Funding from GEO made it possible for UCL Qatar to host this first-of-its-kind workshop in Sub Saharan Africa.

This has resulted in a beneficial collaboration with local institutions in Zambia such as the National Museum Board of Zambia, University of Zambia and National Archives of Zambia to deliver of the first-ever workshop on Innovation Labs in Sub Saharan Africa.

The workshop also inspired a new sense of enthusiasm in participants to make their digital collection accessible online.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Dania Jalees for the infographics, Fred Nuyambe for the photograph and Fidelity Phiri who collaborated on this project.

New Report on Study Abroad and Student Mobility: Stories of Global Citizenship?

By By Guest Blogger, on 20 September 2019

By Nicole Blum

Development Education Research Centre, UCL Institute of Education

In 2017 we received funding from the Global Engagement Office to identify some of the reasons young people decide to study abroad and what they think they gain from the experience. The research, conducted by myself with support from Douglas Bourn, set out to understand whether the learning students have gained resonates with UCL’s global citizenship and student mobility strategies.

The term ‘global citizenship’ has been around for a while, but is often used in different ways. Key authors in the field suggest that it can have a number of dimensions, including a focus on increasing global employability and competitiveness, cultivating greater understanding and appreciation of difference, or critical engagement and radical transformation of inequitable global structures and relationships.

UCL’s definition includes elements of all of these dimensions, and describes global citizens as individuals who: understand the complexity of our interconnected world, understand our biggest challenges, know their social, ethical and political responsibilities, display leadership and teamwork, and solve problems through innovation and entrepreneurship.

Our work was motivated by the common assumption that international experiences for students – including study abroad, overseas volunteering and work placements, and international travel – will result in positive learning about diverse cultures and global concerns.

While there is plenty of research which strongly supports this idea, it has tended to be based on quantitative data from questionnaires completed at the end of an experience. Relatively little research has looked in-depth at student’s own perceptions about their learning while abroad or when they return home.

We interviewed undergraduate students on UCL’s Arts and Sciences (BASc) programme to gain a better understanding of their perceptions.

The data highlighted a range of push and pull factors which influence young people’s study abroad decisions, as well as a wide range of ways in which the experience encourages (or does not) reflection on global issues and on students’ sense of themselves in the world.

Students highlighted the personal aspects of being a ‘global citizen’ when talking about their study abroad experiences:

Studying abroad was the first time I felt like I could call myself a global citizen. Before this, I had some awareness and interest in international issues, but had never left Europe and only travelled for brief periods of time. On returning, I found I had a reverse culture shock, and could relate better to international students studying in the UK.

The evidence also suggested that a number of different kinds of learning take place during study abroad, including about particular topics/ issues, experiences of particular places and/ or exposure to new ideas:

I really do think my sense of history has changed and sense of international politics has changed, and also a sense of what an English person is had changed.

Learning about colonialism and racism in the Netherlands taught me to reflect more on my own country’s issues and ugly history. Thus, making me think more globally about the lives of individuals who have suffered as a result of colonialism.

While these experiences can be highly significant for individuals, it is important to recognise that transformative learning may not happen without support. Students in this research clearly recognised the value of their study abroad learning and experiences, but also the need for more ways to reflect on this with programme organisers and with peers, particularly if they are to be able to take their learning forward.

UCL clearly sets out the potential outcomes of study abroad, with a strong emphasis on the benefits to participants’ enhanced employability, new experiences and skill development. The students we interviewed tended to agree with these benefits, although they often emphasised one aspect as most relevant to their own experience:

I’m actually probably more open now to going and working in other countries or studying in other countries, and it doesn’t feel impossible, it doesn’t feel like this huge ordeal, like this huge challenge, because ‘Oh I’ve done it now’.

I really thought I was just going to learn French, but actually I got a lot out of it academically. I took quite a lot of … studies in creative art, so video games and the cinema and comic books…. there’s a huge games industry out there but also the arts are quite strong in Montreal. And it sort of convinced me that that was a legitimate career choice. I think before then I’d sort of seen that as … you know creative industries is kind of a pipe dream, or it’s something you do if you get lucky. But actually, out there [in Canada] there are people writing scripts for video games or films or … and the fact that I could study it as an academic discipline made me realise that this is a legit thing … it’s not just this fanciful dream. So actually, I’m now hoping to go into radio.

While this study reveals some of the reasons behind the decision to study abroad, more research is needed to explore more deeply how students themselves understand their experiences of study abroad and the ways in which their learning informs their lives in the future. This is perhaps particularly important in the context of increasingly diverse student groups as well as a rapidly changing world.

For more details about the study, access the full report here: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10078730/

Yenching Academy Scholarship: A life-changing opportunity in China

By By Guest Blogger, on 7 August 2019

By James Ashcroft

The Yenching Academy of Peking University aims to build bridges between China and the rest of the world through an interdisciplinary master’s program in China Studies. UCL History graduate James Ashcroft was among the first recipients of a fully funded scholarship to the programme. Here, he blogs about his experience at the Academy.

I still remember being asked by my then tutor Dr Vivienne Lo to forward an email to my fellow students about a new scholarship programme at Peking University. I had seen so many emails in my time at UCL that I didn’t bother to open it, so I just shared the email and left it at that. For some reason, I later on decided to open that email. I am so fortunate that I did because it quite literally changed the course of my life.

The Yenching Academy Scholarships give graduates from around the world the opportunity to experience China in a very international environment. It’s a fully funded scholarship at one of the best Chinese universities in the world. You get your flights paid for and your accommodation paid for, and you’re taken care of in the most incredible way.

Authentic Chinese experience

It’s a programme which gives you the opportunity to study alongside and make lifelong friendships with some of the brightest and most talented people you’ll ever meet. And for me anyway, it goes beyond your average study abroad programme in a way which makes it a truly authentic Chinese experience.

In my experience, the Yenching Academy Scholarships are relevant to anyone at UCL, whether or not they speak Mandarin or know much about the country. As someone who grew up with lots of friends who spoke multiple languages, it was always jarring that I could only speak English.

The Yenching Academy Scholarships didn’t seem like an obvious fit for me and I couldn’t speak a word of Mandarin at the time I applied. I also didn’t know much about China or its history. This is a really important point to make as I wouldn’t want any student to miss out because they don’t see the relevance to them.

Extremely rewarding

I grew so much during my time at PKU and always felt empowered to step up and contribute to the community of scholars and the university more broadly. One of my highlights was sitting on the executive organising committee for The Yenching Global Symposium, which brought together 100 or so Yenching scholars, alongside 50 graduates from PKU and 50 other students from around the world. The event has taken place every year since and it’s been extremely rewarding to see it become the success that it has.

My education at PKU was essentially a Masters in China Studies, and the qualification included elements of economics, history, international relations, law and society. I was also required to study four hours of Chinese a week, and could choose between attending classes taught in English, Mandarin or both.

My thesis analysed the Chinese government’s long-term development plan for the game of football in China in order to explore the intersection between economics, politics, and the country’s sense of place in the twenty-first century world order.

Incredible conversations

Education was only part of the picture though – as with any programme like this – and whenever I think about my time in Beijing, I think about the people I met there. I got a tremendous amount from speaking to my classmates, and we had the most incredible conversations and invigorating debates on some really important global issues.

When you’re living in another part of the world, these things can really bring you together. I’m still in touch with so many people with whom I studied – some even on a daily basis. I often meet up in person with Yenching Scholars when they come to London and I’ve visited a number of them in their home countries too.

Truly global environment

My time at Peking University has opened my eyes to working in the 21st century within a truly global environment, and I am certain that countless other students would benefit from this great opportunity.

I am always happy to speak to UCL students about my experiences as I feel very passionate about the university being represented each year in the latest cohort of Yenching Scholars. When that email comes round this year, please think carefully about opening it because it might change your life as well.

UCL alumni interview: Himani Gupta, artist

By ucypsga, on 1 August 2019

Himani Gupta studied international real estate and urban planning at The Bartlett from 2011-2012. Having worked as a spatial designer and a consultant for Ernst & Young in Delhi, Himani is now working full time as an artist, specialising in painting.

Himani Gupta studied international real estate and urban planning at The Bartlett from 2011-2012. Having worked as a spatial designer and a consultant for Ernst & Young in Delhi, Himani is now working full time as an artist, specialising in painting.

We spoke to her to find out more about her experience at UCL and how she stays in touch with the UCL community.

How did you come to study at UCL?

Firstly, because I love the campus and I’d been following it for a while. Secondly, I found the work that’s been done at the Bartlett very relevant to the direction I wanted to go in professionally. Before doing my masters I used to be a spatial designer, but I wanted to get onto the other side which was understanding the business of cities and how infrastructure and real estate are developed around them.

How did you find studying at UCL?

It was a really enriching experience because I got to learn about the politics of space in Europe and the real estate markets in China and the Middle East. The freedom we had in terms of things like choosing our dissertation was great. I could also make it more India-centric, which helped me immensely after UCL in terms of getting a job in Management Consulting in the Urban field in India, as I’d written on similar topics for my masters.

Compared to my undergrad degree in Business Studies in India, UCL was more analysis-based. It took some time but once I got used to the structure of the course it opened up a new way of looking at things, which helped me in my job in the real world and still helps me now.

What was it like living in London?

I’ve always loved London so the city was very familiar to me. I lived in Bayswater in West London so I’d cycle or walk down to the campus. We organised Thursday drinks at the UCL bar, which became a hub for us each week. I found the balance between a lot of study and a lot of socialising quite enriching.

It’s all so centrally located and I liked that we had classes in different locations across the campus; I explored all sorts of hidden buildings. Now I’m an artist and my work is about psycho-geography and understanding layers of space, and the fact that I walked quite a bit while studying in London has shaped my approach to my work.

What would your advice be for a student in India looking to study at UCL?

Figure out funding very early on and give yourself a strict budget. Once you have that figured out life at UCL and in London is very easy. At UCL, you have an account to access a student/teaching portal where all the modules and submissions are in one place. It’s really cool because one can study anywhere. UCL has a lot of libraries and quiet corners to study, which was one of my favourite parts. I’d say try and explore as many nooks and corners as possible around the campus.

What aspects of the culture did you enjoy?

The fact that you get to hear a different language every square foot or two. Because I’m a walker I take in and absorb London as I walk through it, and as you do you get an insight into how many cultures and backgrounds exist together in this city.

The art scene and the number of galleries in London is phenomenal and the shops that offer material really works for me. Also, the food! Which is a direct function of the number of cultures that exist here.

Even after graduation, I make it a point to visit UCL on my trips to London to catch up with old and new connections.

How have you kept in touch with the UCL community?

I moved back to India in 2013 but I recently wrote to another good friend of mine from my course who’s very active in New York with the UCL alumni group there. He put me in touch with UCL’s alumni team, and through them I got involved with volunteering in Delhi. I organised a reunion event in Delhi a few months ago – about 26 of us came together for a casual mixer event at the art-themed homestay I run.

I was curious to bring together people from different professions and initiatives not just for myself but for everyone present. It’s also a great way to form new social groups. I now look forward to more events and more people volunteering in Delhi. I’m happy to open up my studio (which can accommodate up to 35 people) to those interested in having an Arts and Culture themed reunion mixer.

Tell us about your work.

I’ve got my hands in a lot of pies! I used to work in spatial design before doing my masters then I came back to India and I started working as a consultant with Ernst and Young. So I used to be in management consulting in the infrastructure and smart cities team.

I’ve also been a painter for the last fifteen years and after deciding to leave consulting I wanted to focus on it full time. My visual arts practice is drawn from my very diverse experiences in education, professions and travels. Urban and spatial exploration has been a research interest of mine for a long time and what I try and study through my art is the idea of psychogeography and understanding the materiality of space. My medium in art is painting primarily and I create large pieces of work. I work with pigments and paint. Lately, I have been creating a lot of smaller works based on mapping.

What are you working on with the Slade?

Through my work as a UCL volunteer, I was introduced to Deborah Padfield, an artist and professor at the Slade who is exploring how chronic pain is communicated through the arts in a project called Visualising Pain.

She wanted to work with a local artist and although pain is not my direct subject, the fact I could use paint and pigment in order to help chronic pain sufferers communicate their pain better motivated me to get involved. I ended up co-facilitating a workshop with Deborah (and others) in Delhi in May 2019. It went really well and made an impact on our participants who battle chronic pain everyday.

How has UCL helped you to achieve your ambitions?

It’s interesting because before coming to UCL I wasn’t particularly motivated to do ‘well’ in the conventional sense – whether that’s an educational qualification or a job – my pace was a lot slower. Which is not necessarily a bad thing but in my case I wasn’t achieving too much or doing too much with my time.

I think UCL and my experience of living in London really inspired me and opened up a channel which I never knew existed in me, which is that of wanting to achieve and working hard. I got into the habit of maintaining a diary, organising myself better, understanding before speaking or describing. I started being meticulous about my work and had I not gone through this change I would still be very bohemian and less results orientated.

UCL would love to hear from more alumni in India and around the world.

Get in touch and find out more about volunteering at ucl.ac.uk/alumni

UCL Summer School shines on: Record student numbers and a packed programme for 2019

By By Guest Blogger, on 26 July 2019

By Rory Herron, Summer School Liaison & Recruitment Officer

By Rory Herron, Summer School Liaison & Recruitment Officer

The 2019 UCL Summer School is now underway and it has been another successful year for student recruitment.

Since launching in 2016 with 99 students, enrolments increased to 380 in 2017; then to 529 in 2018. This year we have over 700 students of 52 nationalities joining us from over 250 universities. Promotion of the UCL Summer school is fully embedded within UCL’s worldwide recruitment activities both in-country and via digital channels, as well as establishing partnerships with overseas universities and organisations.

Summer schools are a well-established vehicle for student mobility, and have been for many years. They appeal to students who are keen to get a taste of studying abroad and gain valuable international experience, but who for various reasons may not yet want to commit to a longer period abroad as part of their study. There has been an explosion of growth in summer schools over the last five years, giving students a huge amount of choice over where they go and what they do.

Wide range of modules

What sets us apart from competitors is UCL’s ranking and reputation, our central-London location, and our ability to offer a wide range of modules from our renowned faculties. All modules meet UCL’s stringent quality framework requirements and are taught on the UCL campus by UCL academics.

Most modules include site visits and excursions to places of interest around London and while on the programme, summer school students enjoy full access to UCL facilities, including all 16 libraries on campus.

Social programme

As well as the broad range of module choices, students on the programme have an option to live in a designated UCL Summer School residence in the city centre and enjoy a unique Social Programme, which ensures that students make the most of their summer in London. Promisingly, 85% of the 2017 cohort said they would consider UCL for a graduate programme so the programme is evidently an excellent introduction London and to UCL.

Student satisfaction

Furthermore, an impressive 99% of the 2018 cohort surveyed said they would recommend the UCL Summer School to a friend. This level of student satisfaction so early on in the formation of the summer school, is a reassuring indicator of better and bigger things to come.

Watch videos following three of our students who took part in the 2016 programme on the UCL Summer School website.

For more information about the UCL Summer School, contact Rhod Fiorini, Director of UCL Summer School at r.fiorini@ucl.ac.uk or Rory Herron, Summer School Liaison & Recruitment Officer at r.herron@ucl.ac.uk .

Ask an Academic: Professor David Osrin

By By Guest Blogger, on 24 July 2019

Professor David Osrin is Professor of Global Health at UCL and a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science. Based in Mumbai since 2004, he works in an urban health research collaboration with SNEHA (the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action).

Researching within the broad remit of urban health, he is particularly interested in complex social interventions and research ethics, and art and science’s utility in raising public awareness of health. We spoke to David to find out more about his life and work in India…

Can you give us a brief overview of your research in India?

My research has come a long way since I first began working in India in 2004. I started out looking at ways to improve the health of newborn babies in the Mumbai region, working with an excellent organisation called SNEHA. More recently though I’ve been working with organisations like SNEHA to tackle violence against women – an increasingly important issue in India.

I also work closely with the Municipal Corporation of Mumbai, the Family Planning Centre of India, and other health professionals in the area.

What got you interested in the subject in the first place?

When I first began working here, I noticed how committed and passionate everyone was about improving public health in India. It was this passion which inspired me to pursue my research to the extent that I have.

While public health has been an issue for a long time, it’s only in the last decade that violence against women has been a mainstream topic in India. Thanks to a number of landmark legal cases the Government has begun to take the issue much more seriously, and I’m so pleased our research techniques are being used to make a difference.

What difference do you hope it will make?

My vision is to contribute to a social transformation that is taking place throughout the world with respect to equality. In the case of India, my hope is that it will continue to lead to a reduction in violence against women. One of the things that stands out for me is that when we bring the local community together, anything is possible!

Can you tell us about the Institute’s relationship with India?

The Institute of Urban Health is not the only part of UCL working in India of course, and there are other colleagues at the Institute doing great work here too. Together with our partners, we’ve succeeded in engaging state level government in India to bring about some significant policy changes. As well as the work I’ve been doing there, Dr Audrey Prost has also achieved some great results with another Indian NGO called Ekjut – on improving the health and nutrition of new born children and adolescents.

What can UCL learn from your time working in India? What can the UK learn?

Aside from collaborating with people with a different background and outlook to my own, I’ve seen the power when communities come together to tackle societal challenges like public health. Legal intervention, emotional support and shelter are needs that we all share, so what we learn in India can be applied to the UK and vice versa.

What are some of your highlights from living in India?

Having being involved in some hugely important and large-scale research projects, in true collaboration with equal partners, to deliver world-class research.

I’m proud of the fact that during my time here we’ve seen the transformation of countless individuals. I’m also really proud of the public engagement work we’ve done, bringing together the disciplines of health, art and science, which led to a hugely successful festival called Dharavi (or Alley Galli) Biennale.

What has it been like working in the Indian slums?

I am very privileged to spend my working days in an informal settlement but not to live there. Not everyone has that privilege. The impact on me has been profound, and the importance I place on certain things is very different now to when I was living in the West.

The challenges associated with finding clean water, a shelter to withstand the elements, and the need for electricity have all given me a greater appreciation of the basic health and wellbeing needs we all share.

What would you like to say to other academics at UCL thinking of collaborating with others in India?

I think they should absolutely collaborate here if they can. In my view, the academic and research capability of teachers in India is on a par with the UK. Also, I’ve never experienced being hampered by the government structures in place in India. In fact, quite the opposite.

The number of people who are willing to participate in the research has also been incredibly valuable for my research. There’s a lot of enthusiasm in India among the public for taking part in research – perhaps more so than the UK.

It goes without saying that the intercultural interaction which informs my research has also enhanced my experience here.

Student recruitment: Better together

By By Guest Blogger, on 19 July 2019

In this guest blog, UCL’s Student Recruitment Marketing (SRM) team explain how they work closely with Faculties and departments across the university to recruit talented students from around the world.

Catherine Thomson, one of the first co-leaders of the UCL Student Recruitment Community of Practice, described student recruitment as everyone’s business. One way or another everyone has a part to play, whether it has a direct or indirect impact on the recruitment of students.

But with so many players involved, how do we make sure that we’re not all pulling in different directions but instead achieve consistency? How do we balance the overall institutional goals with the Faculties’ and departments’ need to reach their targets of recruiting the right number and calibre of students?

Regular meetings

It’s easy to assume we all want the same things, but that’s not necessarily the case. Let’s take the example of China. We have a large cohort of students from China so there is no institutional incentive to drive numbers up as a whole, but yet there is scope for some degree programmes to increase enrolments from PRC. On the surface this creates a conflict between the big, overall picture and the nuance of Faculties and departments.

The key to solving the conundrum is to work together to understand the needs of all the stakeholders, and ensure the right tools are in place to meet those needs. The SRM team meets Faculty counterparts on a regular basis to discuss Faculty recruitment goals and target markets.

We work together to identify where we can consolidate or improve our performance in a particular subject in existing markets, and what activities may be best.

Sharing knowledge and intelligence

On the flip side, the discussions also present an opportunity to identify where the markets prioritised by SRM differ from those identified by a Faculty, and why that might be the case. For example, there may be subject areas which are particularly relevant or where UCL has built up a strong reputation in specific parts of the world where there is little or no wider institutional interest. Sharing knowledge and intelligence is vital, and means that we can dovetail activities to complement each other rather than clash.

Different stakeholders will take the lead at different stages of the student journey too. The diagram below illustrates broadly how prospective students experience UCL as they move from considering us to actively selecting us, and who leads on those interactions at each stage of the process.

In general the initial relationship is with the institution as a whole, and deepens with the specific programme or department as the journey progresses. Again, conversation and work between the centre, the Faculties and departments is essential to ensure that opportunities are maximised, the right tools are there and that we’re working to make the experience as seamless as possible for students.

In general the initial relationship is with the institution as a whole, and deepens with the specific programme or department as the journey progresses. Again, conversation and work between the centre, the Faculties and departments is essential to ensure that opportunities are maximised, the right tools are there and that we’re working to make the experience as seamless as possible for students.

There are always improvements to be made, but initiatives such as the recruitment activity and communications mapping exercises and the use of the Kano model to help clarify what needs to be done by all the players means we can see where we need to focus our attention.

If you have any questions about UCL’s student recruitment strategy and activities, please contact Neil Green, Head of Student Recruitment Neil Green at neil.green@ucl.ac.uk

Ask an Academic: Professor Sue Hamilton, Director of the UCL Institute of Archaeology

By ucypsga, on 30 May 2019

Professor Sue Hamilton is Professor of Prehistory and since 2014 has been Director of the UCL Institute of Archaeology.

Professor Sue Hamilton is Professor of Prehistory and since 2014 has been Director of the UCL Institute of Archaeology.

Sue is Principal Investigator of the Rapa Nui (Easter Island) Landscapes of Construction Project (LOC), which has been substantially funded over the past decade by the British Academy and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

It has been undertaken in collaboration with UK Universities of Bournemouth (co-investigator), Manchester (co-investigator), Cambridge and Highlands and Islands, together with representatives of the Chilean Council of Monuments, MAPSE (the island’s museum) and the indigenous peoples communities of Rapa Nui.

Sue and her team were the first British archaeologists to work on the island since 1914, when the English archaeologist and anthropologist, Katherine Routledge carried out the first true survey of the island.

We spoke to Sue to find out more about her unique partnership with the local indigenous community of Easter Island, and how she navigates the relationship with both the local community and the Chilean government while conducting her research.

What is the project about?

The project studies the sites and artefacts of the Easter Island statue building period (AD 1200-1550) as an interconnected, integrated whole, on a landscape scale. It has involved excavation, mapping of monuments, assessment of threats to preservation and studies of the island’s ancient and present environment.

What’s it like to work on Easter Island?

It’s a remote place, being a tiny Pacific island some 5000 km from the nearest mainland of Chile and 2,500 km from the nearest island, Pit Cairn. The local indigenous community is highly politicised, so all sorts of major internal events continually happen. If you have just a few months away it’s likely there will be completely different ground rules when you get back.

I have been formally working on Rapa Nui (which is the local name) since 2009. Much of the island is covered in prehistoric remains and is a UNESCO designated World Heritage Landscape. In 2017, the Chilean government and National Parks Authority signed over the management of the National Park to the local indigenous community, Ma’u Henua and in 2018 we signed an agreement with the community that ‘LOC’ would advise them on archaeological issues in the park. By the time we got back in January 2019, there were several new people involved in discussing what LOC might work on and the methods to be used. Alongside this, there were new island tensions and new agreements of access to land and methodologies of documentation. Such negotiations to undertake work and its precise format can only be resolved by face to face meetings on each occasion of return to undertake fieldwork. It’s very much based on people trusting you; being able to talk to different individuals, and importantly giving people your time.

How does this partnership differ from others you might have, say with the local community in Camden?

There’s a lot of delicacy that comes with global partnerships. There are all sorts of tiny nuances. Easter Island is famed for its colossal statues and these prompt high profile discussions of the apparent collapse of the society that produced them and of the threats to the conservation of the island and its archaeology in the present; and any work on issues of its heritage always hits the newspapers – even the tiniest thing. Today the local community do at last have a very powerful gift in their hands in managing their heritage, and equally they have had a very embittered history of enormous threats to the survival of their society and traditions, which must be touched upon with empathy and sensitivity.

From the time the island was discovered by Europeans in the 18th century the local community had all sorts of terrible things happen to it, in no small part because of European contact brought disease, and ultimately loss of access to their lands. Katherine Routledge in 1914 recorded just 250 islanders compared with a population of maybe 6,000 during the statue building period. With the increasing return of land by the Chilean government in the late 20th century, and the current role of Ma’u Henua the islanders are significantly economically empowered because they have a heritage that tourists pay a heavy Park admissions fee to see.

There are currently about 6,000 islanders and 75,000 tourists go there every year. But this means that there are things that we might think are best for Rapa Nui’s extraordinary archaeology that might not be so good for tourism. We need to take things slowly and take care in giving opinions as ‘privileged academics’, and not for example just leap in with a comment because someone says that’ll make a great quote in a national or international newspaper.

You have to remember it’s not your past, it’s their past, and I think it’s particularly so on Rapa Nui because it’s living heritage – the statues and associated monuments still have an active meaning to the Rapanui; they are not ruins of a now dead past. So a living heritage is something you can’t dabble with and think it won’t affect people.

How did you first come to work on the island?

I was working in Italy and invited my colleague, Colin Richards who worked on similar sites in the UK to come out and see the Italian ones. He spent rather a lot of time on the beach rather than working! So I went down to the beach one day and he was reading Thor Heyerdahl’s Aku-Aku, which is a 1950s popular book about Easter Island. Colin said we ought to go visit Easter Island and when we did we were just stunned by the archaeology and its great potential for new work. It was a great leap for both of us but we ended up co-directing our AHRC funded LOC project. It’s the most amazing archaeology I’ve ever worked on.

How closely are you now working with the Island’s local community?

We are currently doing research into the impact of soil erosion on the island’s archaeology and have been working on the massive ceremonial monuments by the sea and recording the extent to which many are near collapse. Conservation-related work is a good way to be working with the local community and stakeholders, and trying to do something that they want. For instance, they will put their effort into sites that tourists would particularly want to go and see, because that makes current economic sense. For us, this concurrently generates research information about the range and distributions of different categories of archaeological site. There are however numerous archaeologically very important sites beyond the tourist trail that may be key for better understanding Rapanui’s past and we have to find a pathway between both considerations.

Currently, most media people contact me about Easter Island to ask about climate change and rising sea levels and threats to the statues and their associated ceremonial monuments which wrap the island’s coastline. In many cases it’s not actually the sea that’s the most significant problem; it’s mismanagement of the landscape in modern times and the erosional impact of increased rainfall. Huge surfaces of the island are losing their soil. There are about 1,000 statues – which people don’t realise, and a lot of them at the main site where they were quarried are buried so there might be around 3,000. They are variously deteriorating due to lichen growth and the effects of atmospheric salt which penetrates the whole island environment.

Residential fieldwork uniquely creates local friendships; we stay with a local family business for a month each year, and the family have become special friends and are very supportive. A few years ago I obtained a bursary for a Rapanui archaeology student, Fran Pakomi, to come over to the UK and she was trained on our UCL fieldwork course and stayed in my house. It’s these types of visits and exchanges that maintain and solidify connections and trust with distant local communities because they are at the cross-over between work and friendships.

What’s been your best archaeological discovery over there?

I suppose that one of the most dramatic is something that people knew a little bit about, but which we’ve documented and rediscovered many more of, are the carved giant pairs of eyes on the walls of the statue quarry. I always remember reading that in the Marquesas they believed rock to be living and that when rock was taken for monument building, the rock regrew again. We’ve found eyes that you can no longer see by using photogrammetry .

The other one’s a bit more esoteric – it’s just how interconnected things are and how many little stones were moved and how in being impressed by the physically big (such as enormous statues) you can lose the insights provided by small scale things. The builders of the statue period took giant flat cobbles from the beach and must have moved millions of them inland to make pavements and terraces outside of the houses they built. On land, large screes of volcanic rubble were move to create rock mulch, to protect the soil. The kind of human chains involved in moving millions of stones hand-to-hand from seashore inland and redistributing the volcanic rubble is quite incredible.

In the 20th century, the local community was provided with Chilean social housing, which is now seen by many as something to be rejected and demolished. We are now studying this housing and how interestingly a lot actually incorporates aspects of ancient traditions. Now on Rapa Nui there is beginning of building a sort of Polynesia of the modern imagination and an aligned very inventive local architecture that incorporates what they and potentially tourists may think Polynesia is. It’s fascinating to live through these changes as a regular visitor and it gives and insights into local priorities.

Fieldwork in distant places, and living with a local community over numerous years, accretes to make the dynamics of ancestry and heritage recording and isolating conservation and preservation priorities a mixture of diplomacy, empathy and co-production of research to secure the futures of a living past.

Close

Close