St Andrew’s Church, formerly in Wells Street, now at Kingsbury, Middlesex

By the Survey of London, on 1 April 2016

Remnants of old urban churches occasionally get reconstructed on suburban sites when they have outlived their usefulness. An example is Wren’s All Hallows, Lombard Street from the City of London, whose incongruous tower surprises motorists as they flash through Twickenham along the A316. But for a complete Victorian church, not of the first architectural order, to have been transferred lock, stock and barrel from the West End out to Metroland is surely unique. Yet that is what happened to St Andrew’s, Wells Street, Marylebone, rebuilt in 1933–4 as St Andrew’s, Kingsbury.

St Andrew’s Church, Kingsbury, from the south-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

The key to the reuse of the church was the wonderful treasure house of its fittings, recognized even at a time when Victorian art and architecture were generally held in low esteem. The Wells Street church had an unusual history. Like many Victorian churches it was erected to boost church accommodation and, hopefully, attendances, in a densely inhabited urban area. But not long after it was completed to designs by Samuel Daukes in 1847, a rival Anglican church, the celebrated All Saints, Margaret Street, was constructed just round the corner. Both were controversially High Church foundations and in their early days attracted fashionable congregations who came to admire their splendid church music and fine fittings. The actress Sarah Bernhardt was married at St Andrew’s in 1882, but the marriage did not last.

View of the interior from the south-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The nave from the south-east (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

View through to the nave from the south aisle (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

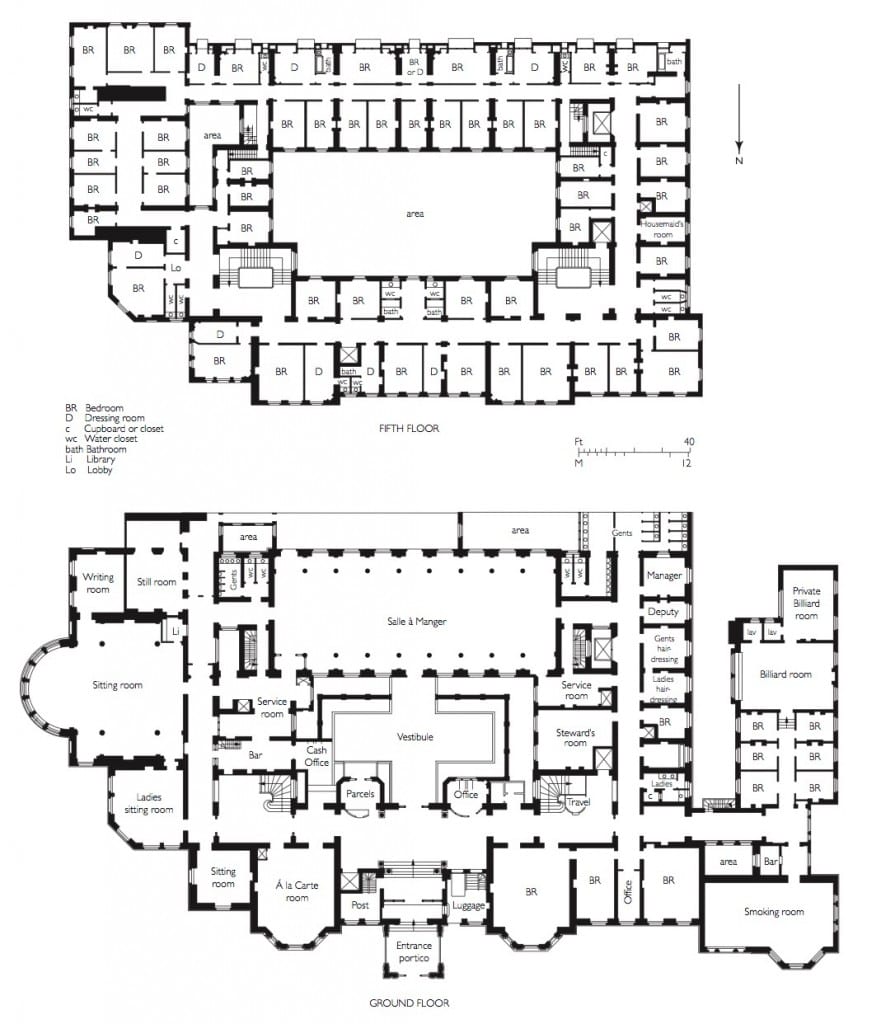

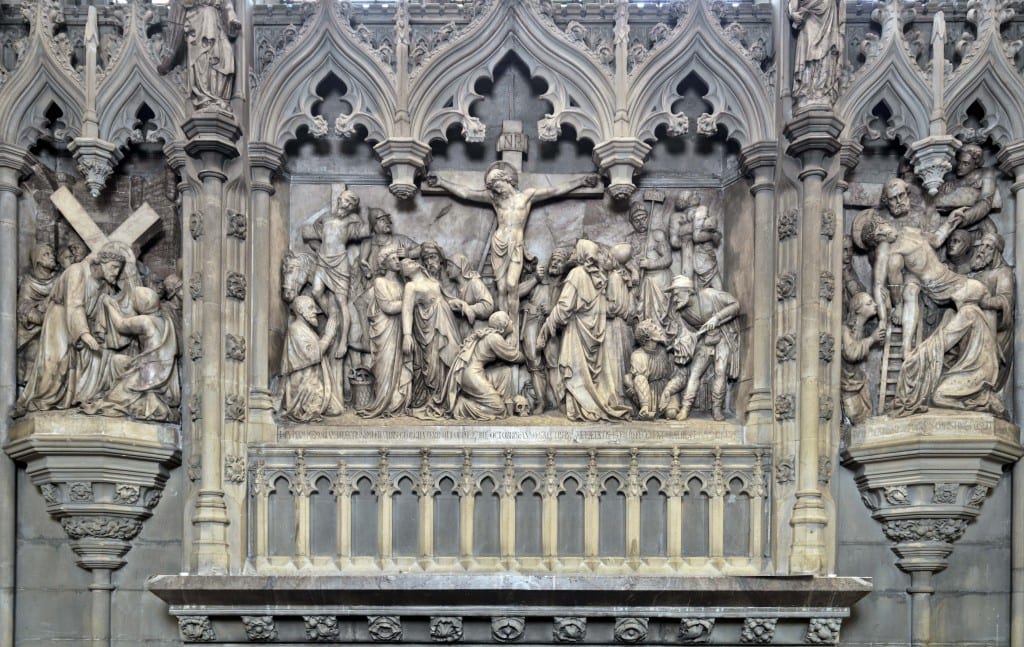

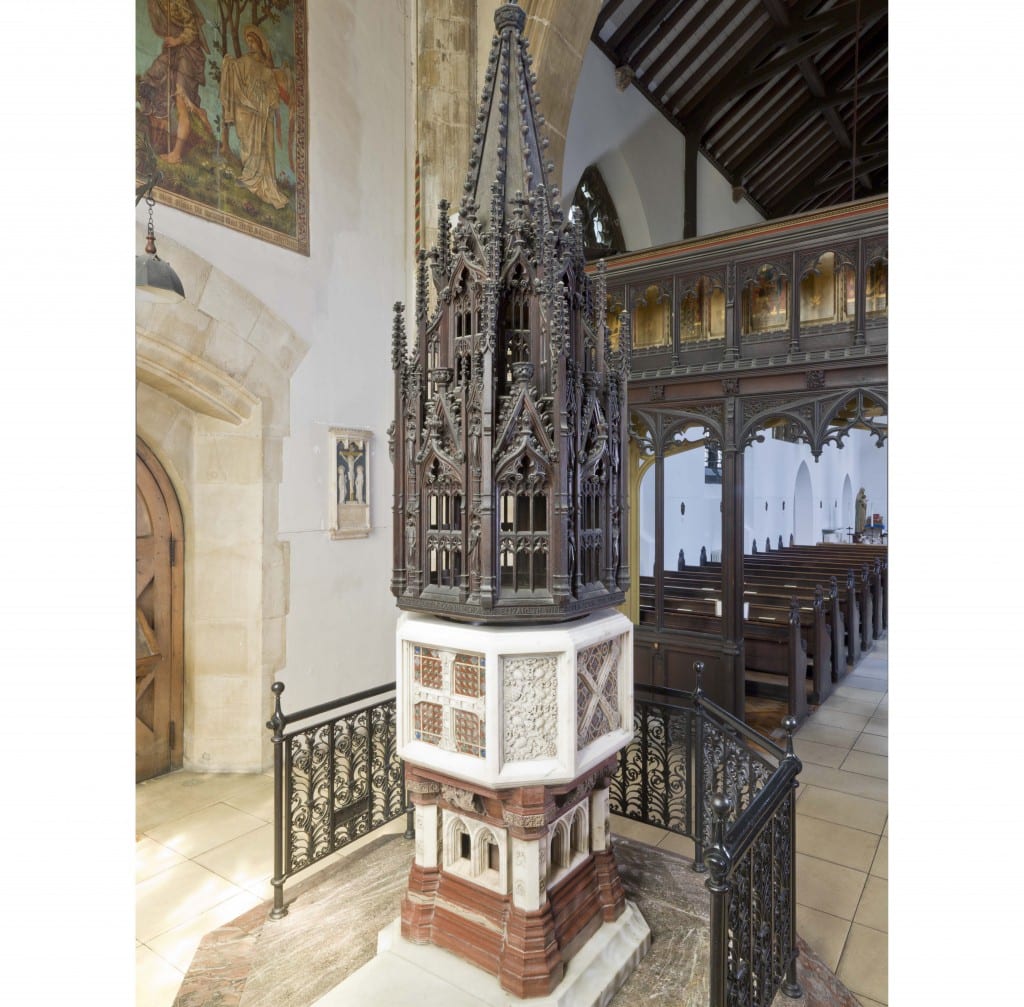

The church’s third vicar was Benjamin Webb, secretary of the Ecclesiological Society and editor of its pugnacious journal, The Ecclesiologist. To keep up with All Saints, Webb commissioned fittings from the leading architects and artists of the Victorian church-building movement. Pugin had already contributed an altar and one window, and Butterfield (the architect of All Saints) a lectern. To these Webb soon added a wonderful wall monument by William Burges to his predecessor, James Murray, and then a whole series of fittings by G. E. Street. Chief among these was the reredos, developed in stages to cover the whole east wall, with stone niches and alabaster figures and scenes carved by Webb’s protégé, the sculptor-carver James Redfern. The font is also Street’s, but its tall canopy was added after Webb’s death by J. L. Pearson, who also tucked in sedilia beside the reredos. Add in copious stained glass by Clayton and Bell and some unusual decoration of the sacristy contributed by G. F. Bodley, and you have one of the richest collections of Victorian church fittings in existence.

The chancel from the west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Detail of the reredos designed by G. E. Street (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The altar designed by A. W. N. Pugin (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The more conspicuous All Saints was better able to withstand the loss of local population and the vagaries of church attendance in twentieth-century Marylebone than St Andrew’s. A commission proposed in 1929 the unusual solution of taking the latter down and re-erecting it elsewhere. Kingsbury, a rapidly growing district of Middlesex next to Wembley, was identified as the best site; it had a small and inadequate ancient church in an enormous churchyard, so that was the place identified for its relocation. So in 1933–4 this ‘unique casket of architectural jewels and decorative treasures’ was removed and rebuilt in remarkably faithful form by the builders Holland & Hannen and Cubitts, under the architect W. A. Forsyth’s direction. The interior at Kingsbury looks almost the same as it did in Marylebone, but enjoys much better light as it is not blocked in by surrounding buildings. Because the church is now free-standing, its sides and east end look a bit different. But standing as it does on an eminence above the road, St Andrew’s is now seen to superior advantage than when it was hemmed in among buildings along a nondescript Marylebone street.

Monument to James Murray, by William Burges (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The marble font by G. E. Street, with metal cover by J. L. Pearson, viewed from the south-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Detail of the chancel screen (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

View of the metal pulpit by G. E. Street (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The west window with stained glass by Clayton & Bell (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Close

Close

![The Langham Hotel (by The Langham, London, reproduced with a Creative Commons licence via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)])](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/files/2016/03/Langham-Wikipedia-Commons.jpg)