The Survey of London, December 2017

By the Survey of London, on 29 December 2017

Recently we have been looking through our archive on the history of the Survey of London, which traces its beginnings to the 1890s. These large cloth-bound boxes brimming with letters, newspaper cuttings, photographs and pamphlets include detailed reports on the progress of the Survey.

A pamphlet recording the progress of the London Survey Committee, as the Survey was formerly known, at Midsummer 1929.

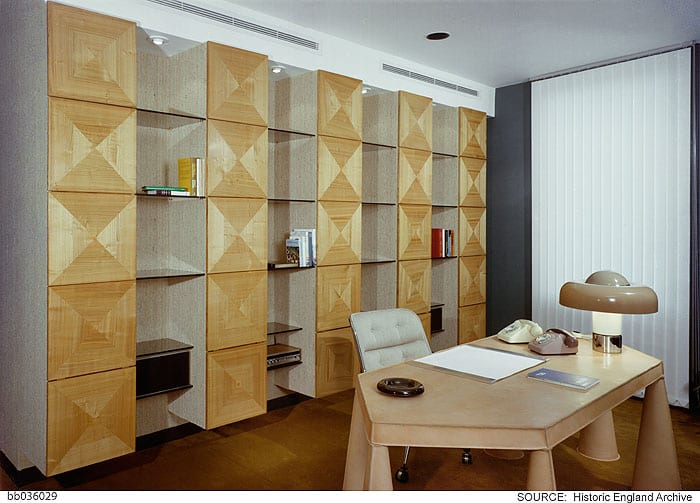

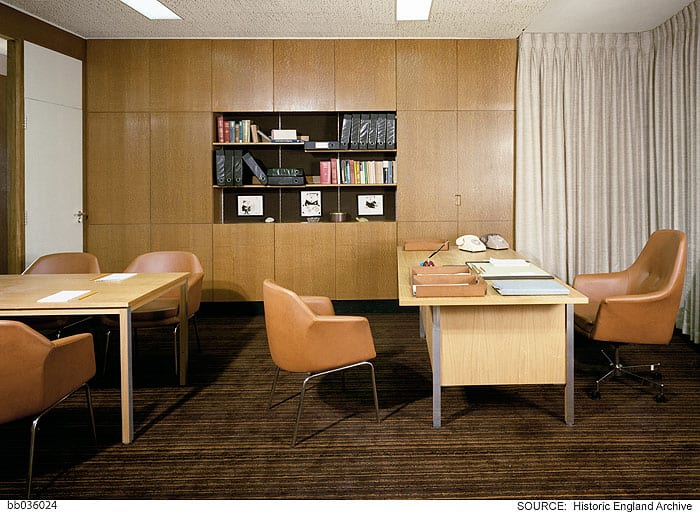

As it is customary during the festive season to reflect on recent achievements, current research, and plans for the future, we think it might be timely to share an update on the current progress of the Survey. 2017 has been an important year for the Survey of London, marked by the publication of Volumes 51 and 52 on South-East Marylebone by Yale University Press, supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. We are delighted that these volumes, which document a rich and varied part of the capital, have been received with glowing reviews:

- “Superbly researched, well written and comprehensively illustrated…” – John Martin Robinson, Country Life, October 2017.

- “These two [volumes] cover a chunk of the historic West End in unrivalled detail following years of rigorous research…” – Robert Bevan, Evening Standard, December 2017.

The draft chapters for these volumes have been made freely available online via our website.

Covers of Volumes 51 and 52 of the Survey of London on South-East Marylebone, published in Autumn 2017.

The Survey is following up its two volumes on South-East Marylebone with a study of South-West Marylebone, covering the area west of the boundary of the previous volumes as far as Edgware Road. A comprehensive study of Oxford Street is also underway to produce a volume covering both sides of the street from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch. As the longest continuous shopping street in Europe since the eighteenth century, Oxford Street is a unique phenomenon. Though it has witnessed almost continuous change, it has never lost its popularity. The traffic, the crowds and the modes of transport will be an equal part of the Survey’s study along with the buildings and shops of Oxford Street. Publication date is estimated as 2019.

View of Oxford Circus taken from the roof of Spirella House, 266–270 Regent Street, looking north-west. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

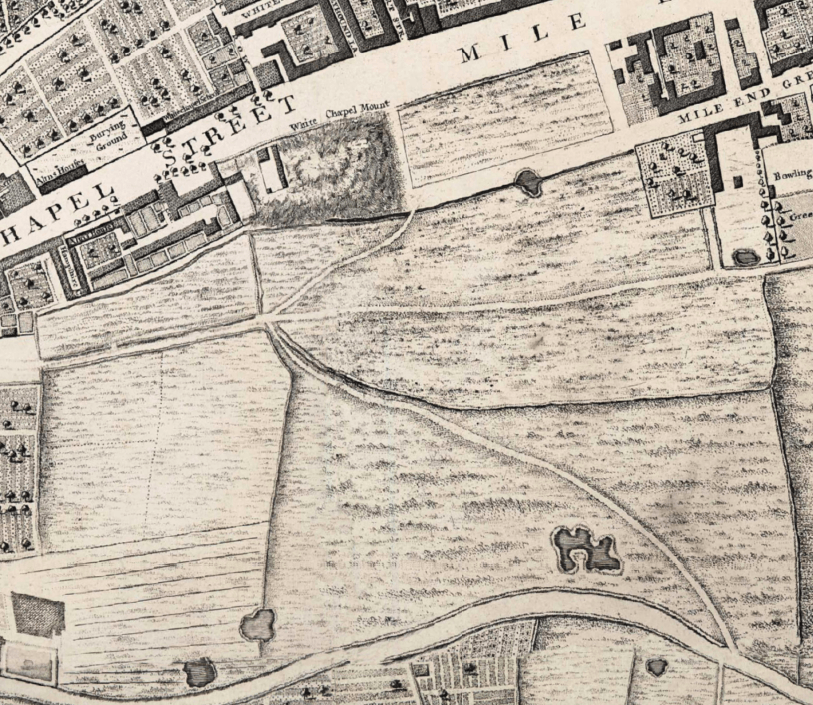

Research is continuing in Whitechapel, an area with a multifaceted history that is currently in the throes of intense change. In Autumn 2016 the Survey launched a public collaborative website, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’, with the involvement of the Bartlett Centre of Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL and supported by a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This ongoing project is an experiment in the public co-production of research, which during the last year has encompassed oral-history interviews, walking tours, exhibitions, and film viewings, all in addition to the combination of rigorous research, field investigation and architectural drawings that is the mainstay of the Survey of London series.

View of Whitechapel Road in 2015, looking east towards the City. (© Survey of London, Derek Kendall)

As many of our readers will know, the Survey has been based at the UCL Bartlett School of Architecture since 2013. Research has recently begun towards an in-depth study of University College London for the Survey’s monograph series, which is devoted to buildings and sites of particular note. The forthcoming monograph will focus on UCL’s Bloomsbury campus, the historic core of the university’s estate. Publication date is intended as 2026, to coincide with celebrations for the bicentenary of the university’s foundation.

View of UCL’s main quadrangle from Gower Street, looking east towards the dignified Corinthian portico of the Wilkins Building. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

Close

Close