Did the end of Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign cause Russia’s mortality crisis?

By Sean L Hanley, on 4 November 2013

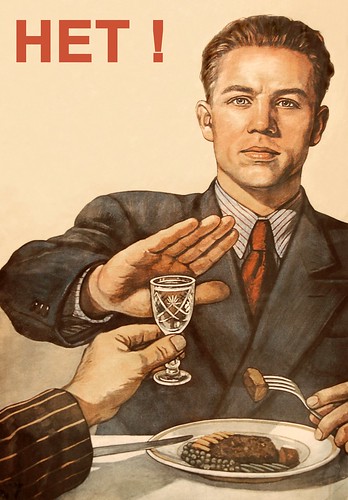

Photo: Vladimir Morozov CC-BY-ND

Russia experienced an extreme spike in death rates in the immediate aftermath of the break-up of the Soviet Union. Jay Bhattacharya, Christina Gathmann and Grant Miller write that while this has typically been explained using political and economic arguments, the real cause of Russia’s mortality crisis may have been the end of Mikhail Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign.

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced a 40 per cent surge in deaths between 1990 and 1994. As a consequence, life expectancy for men declined by 6.6 years from 64.2 to 57.6 years. The magnitude of this surge in deaths – coupled with the Soviet Union’s international prominence – has prompted observers to term this demographic catastrophe the ‘Russian Mortality Crisis.’

What caused this dramatic increase in mortality? Many people attribute the Russian mortality crisis to political and economic turmoil that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, and to restructuring and reforms during the 1990s. We develop an alternative explanation for the observed pattern: the demise of the reputedly successful 1985-1988 Gorbachev Anti-Alcohol Campaign.

The Gorbachev Anti-Alcohol Campaign was unprecedented in scale and scope – and it operated through both supply and demand-side channels, simultaneously raising the effective price of drinking and subsidising substitutes for alcohol consumption. At the height of the campaign, official alcohol sales had fallen by as much as two-thirds (Russians responded by increasing home-production of alcohol called samogon – although our estimates suggest not by nearly enough to offset the reduction in state supply). In practice the campaign lasted beyond its official end – restarting state alcohol production required time, and elevated alcohol prices lingered.

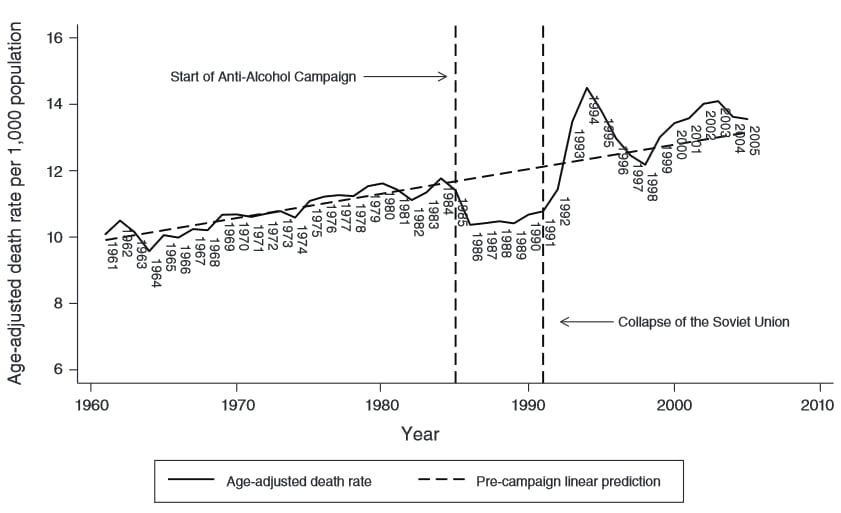

Figure 1 illustrates our basic logic. Age-adjusted Russian death rates had been increasing linearly between 1960 and 1984, plummeted abruptly with the start of the campaign in 1985, remained below the campaign trend throughout the latter 1980s, rose again rapidly during the early 1990s to a temporary peak in 1994, and then largely reverted back to Russia’s long-run trend.

Figure 1: Age-adjusted death rates in Russia (1960-2005)

Close

Close