This year, 2-13 June, SSEES is running the second UCL Global Citizenship ‘Danube’ Summer School on Intercultural Interaction. This is one of the four summer schools that make up the first year of UCL’s Global Citizenship Programme. The Danube Summer School brings together nearly one hundred students from across the University to learn about the Danube and the people that live along its banks. Coordinated by Tim Beasley-Murray and Eszter Tarsoly, the Summer School draws on the expertise of a wide range of SSEES academic staff, language teachers, and PhD students.

Below is a text from the Danube Summer School’s blog that explains the rationale for the Danube-on-Thames project, one of the Summer School’s outputs.

Historically, the region through which the Danube flows has been a region of extraordinary cultural, ethnic and linguistic diversity. The realm of Empires (the Ottoman and Habsburg) that were multi-, rather than mono- ethnic, this was a region that did not care much for neat borders that separated one group of people from another. Here, you used to be able to find Serbian villages dotted in what was otherwise Slovak countryside, German- and Yiddish-speaking towns wedged between Romanian and Hungarian villages, pockets of Turks and other Muslims, Christians of all denominations (Orthodox, Catholic and varieties of Protestants) living across the region, and everywhere settlements of Germans (the so-called Danube Swabians or Saxons) as well those Danubian cosmopolitans, Jews, both Sephardim and Ashkenazim, and different groups of Roma.

A good, even clichéd image, of this cultural and ethnic plurality, as drawn, for example, by the Austrian writer, Joseph Roth, could be found in the classic Danubian café with its hubbub and chatter in many languages, its newspapers on sticks in German, Hungarian and Romanian, its Romany band playing music that draww on a complex fusion of musical traditions, its Jewish doctor playing chess with a Christian lawyer.

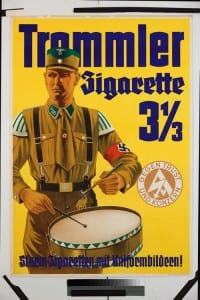

Today, much of this diversity has gone. The collapse of the multi-ethnic empires and the endeavour to create single-nation states, particularly following the First World War, started to tidy up the region and sorted people into national boxes. This process was continued in a much more violent way with the murder of most of the Danube’s Jews and a significant part of its Romany communities in the horrors of the Second World War. After the Second World War, this violence continued with the expulsion of the bulk of Germans from ‘non-German’ national territory – and also, to an extent, the removal of Hungarians from the more-spread out territories that they had previously occupied.

The raising of the Iron Curtain along the banks of the Danube, between Communist (Czecho)Slovakia and Hungary and capitalist Austria and between Communist Romania and non-aligned Yugoslavia, dealt another serious blow to the Danube as a site of intercultural flow. Most recently, the ‘ethnic cleansing’ that accompanied the Balkan Wars of the 1990s was a further step in the homogenization of the Danubian region.

The result is that the Danubian interculturality that this Summer School seeks to explore is not necessarily best explored on the banks of the Danube itself. Where then to look for it? (more…)

Filed under Uncategorized

Tags: Austria, Balkans, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Danube, Germany, Habsburg, Hungary, London, Ottoman empire, Poland, Romania, Slovakia

No Comments »

Close

Close