Danube-on-Thames: The New East Enders

By Sarah J Young, on 30 May 2014

This year, 2-13 June, SSEES is running the second UCL Global Citizenship ‘Danube’ Summer School on Intercultural Interaction. This is one of the four summer schools that make up the first year of UCL’s Global Citizenship Programme. The Danube Summer School brings together nearly one hundred students from across the University to learn about the Danube and the people that live along its banks. Coordinated by Tim Beasley-Murray and Eszter Tarsoly, the Summer School draws on the expertise of a wide range of SSEES academic staff, language teachers, and PhD students.

Below is a text from the Danube Summer School’s blog that explains the rationale for the Danube-on-Thames project, one of the Summer School’s outputs.

Historically, the region through which the Danube flows has been a region of extraordinary cultural, ethnic and linguistic diversity. The realm of Empires (the Ottoman and Habsburg) that were multi-, rather than mono- ethnic, this was a region that did not care much for neat borders that separated one group of people from another. Here, you used to be able to find Serbian villages dotted in what was otherwise Slovak countryside, German- and Yiddish-speaking towns wedged between Romanian and Hungarian villages, pockets of Turks and other Muslims, Christians of all denominations (Orthodox, Catholic and varieties of Protestants) living across the region, and everywhere settlements of Germans (the so-called Danube Swabians or Saxons) as well those Danubian cosmopolitans, Jews, both Sephardim and Ashkenazim, and different groups of Roma.

A good, even clichéd image, of this cultural and ethnic plurality, as drawn, for example, by the Austrian writer, Joseph Roth, could be found in the classic Danubian café with its hubbub and chatter in many languages, its newspapers on sticks in German, Hungarian and Romanian, its Romany band playing music that draww on a complex fusion of musical traditions, its Jewish doctor playing chess with a Christian lawyer.

Today, much of this diversity has gone. The collapse of the multi-ethnic empires and the endeavour to create single-nation states, particularly following the First World War, started to tidy up the region and sorted people into national boxes. This process was continued in a much more violent way with the murder of most of the Danube’s Jews and a significant part of its Romany communities in the horrors of the Second World War. After the Second World War, this violence continued with the expulsion of the bulk of Germans from ‘non-German’ national territory – and also, to an extent, the removal of Hungarians from the more-spread out territories that they had previously occupied.

The raising of the Iron Curtain along the banks of the Danube, between Communist (Czecho)Slovakia and Hungary and capitalist Austria and between Communist Romania and non-aligned Yugoslavia, dealt another serious blow to the Danube as a site of intercultural flow. Most recently, the ‘ethnic cleansing’ that accompanied the Balkan Wars of the 1990s was a further step in the homogenization of the Danubian region.

The result is that the Danubian interculturality that this Summer School seeks to explore is not necessarily best explored on the banks of the Danube itself. Where then to look for it? As is often the case when trying to think globally, it is best to start by thinking locally. Since the fall of the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe in 1989, with the flow of refugees from the Balkans in the 1990s, and now since the accession of most of the Danubian countries to the European Union (Slovakia and Hungary 2004, Bulgaria and Romania 2007, and Croatia 2013), migration from the Danubian region to the United Kingdom has been substantial. These migrations to the UK added to the already pre-existing Danubian communities that arrived over the course of the 20th century. The result of this is that, in particular, it is now possible to speak of a Danubian London. In London today, according to the office of the Mayor of London, there live nearly 175,000 Londoners who were born in the core eight Danubian countries.

Here, in this great city of dazzling diversity, Danubians mingle once again: Hungarians sip coffee in Austrian cafés, Bulgarian waiters serve the Easter lamb in Romanian restaurants, a Serbian Gypsy orchestra plays to an audience that includes enthused Germans and Slovaks. Of course, this Danubian city is only one interlocking part of a myriad of other plural Londons and the new Danubian Londoners are learning about and contributing to the interculturality of all Londoners, their British-Bengali, Polish, Chinese, English, Irish or Somali neighbours.

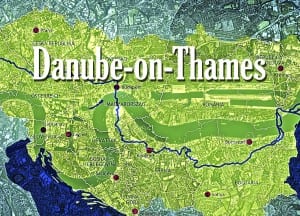

In this part of the GC Danube Summer School, we are aiming to imagine and explore Danubian London. But first to imagine, to conduct an optical and spatial thought-experiment: half-closing our eyes, we are trying to superimpose the well-known (at least to the millions of UK residents who watch Eastenders) curves of the Thames, as it passes through London, onto the cultural landscape of the Danube from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. Or, alternatively: we are trying to superimpose the long and winding course of the Danube, from its beginnings as a bubbling mountain stream to its stately meandering as a vast river in its lower reaches, onto the urban and suburban sprawl of London, from well-heeled Richmond to the lunar landscape of the far Eastern docklands. Danube-on-Thames. London-on-Danube.

We shall map this New Danubian London, this new and imaginary Royal and Imperial Borough of Danube-on-Thames. We shall get to know its diverse citizens, where they work, where they talk, where they drink coffee, beer, slivovice or rakija, where they worship their gods. We shall talk to them – in their own languages as well as in the lingua franca of London, so-called English. We aim to find out about their aspirations, their disappointments, what they are taking from their new environment and what they are bringing to it.

We shall explore their experiences of intercultural interaction – whether as intercultural friction or intercultural flow – both here and in the Danubian region. We shall discuss questions of national, regional, metropolitan, and global identity. Ultimately, we are interested in the relationship between learning to live together as citizens of (Danubian) London and learning to live together as global citizens. To do this, we shall use a mixture of media (short films, podcasts and interviews, blog entries, psycho-geographic and creative writing, photographic diaries and essays) where we shall also reflect on our own engagement in and co-citizenship of London, this global city.

Tim Beasley-Murray is Senior Lecturer in European Thought and Culture at UCL SSEES. Eszter Tarsoly is Senior Teaching Fellow in Hungarian Language at UCL SSEES. The Danube Summer School runs from 2 to 13 June 2014.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL

Close

Close