By Dr Philipp Koker, Honorary Research Fellow at UCL SSEES

This post originally appeared at http://presidential-power.com/ and is reproduced with kind permission.

The controversy over Poland’s constitutional court triggered by president Duda’s refusal to appoint judges nominated by the outgoing Sejm and passage of legislation to legitimise his and the new government’s behaviour has so far dominated the presidency of Andrzej Duda (for a summary see Aleks Szczerbiak’s post here). Now, Duda is once again in the line of fire following his refusal to appoint ten out of thirteen judges from lower-level courts to higher positions. Thus, although the individuals put forward by the National Judiciary Council (a committee formed of 17 judges, the minister of judges and 5 political nominees) are far from uncontroversial, the relatively unchecked power of the president in the area of judicial appointments and the government’s plan to reform the judiciary continue to be the most prominent battlefields of Polish politics today.

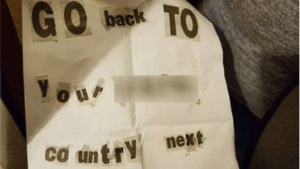

President Duda appoints ‘his’ nominee Julia Przyłębska as judge of the Constitutional Tribunal on 9 December 2015| © prezydent.pl 2015

The Polish constitution, like so many others (irrespective of this being intentional or not), remains vague on a number of presidential duties and prerogatives. Article 179 of the 1997 Constitution thus states with regard to appointments of judges that “judges are appointed by the president on the suggestion of the National Judiciary Council” but gives no further instructions on the procedures or an eventual right of the president to refuse such nominations. Constitutional scholars widely agree that presidents may refuse the nomination of any candidate for public office (irrespective of judge, professor or prime minister) on the grounds of a person’s lack of formal and legally required qualification or reasonable doubts about their loyalty to the constitution. While this generally follows from presidents’ inaugural oath to uphold and protect the constitution, the rejection of nominees for political or personal reasons arguably has no legal basis.

Duda’s refusal to appoint the judges met with particular opposition due to the lack of justification for his decision. Before being proposed candidates for judicial promotions are vetted by the National Judicial Council; if their application is denied they can appeal the decision in court. An additional vetting by the president beyond formalities thus appears not only unreasonable but also adds the complication that there is no prescribed legal way to appeal his refusal to appoint a nominee. Many conflicts over constitutional clauses along the lines of “the president appoints/signs/etc” fall into the category of conflict between two constitutional organs and can be adjudicated by the constitutional court by the ways of a standard procedure. Yet as both the National Judicial Council and the rejected nominees lack ‘organ quality’, neither of them can easily challenge the president’s decision. The latter became clear in the only other case judicial promotions at lower courts were refused by the president. In 2007 Duda’s pre-predecessor Lech Kaczynski (the deceased twin-brother of current Law and Justice party leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski), created a precedent for Duda’s actions by declining to appoint nine judges. The nominees’ constitutional complaints were eventually rejected after four years of deliberations as the justification was that the implementation of administrative law by the president does not fall within the remit of the Constitutional Court. The Supreme Administrative Court likewise rejected the complaints and subsequent further constitutional complaints were also rejected so that the case now (still) lies with the European Court of Human Rights (for a longer summary, see the report of the Helsinki foundation here).

Newspapers have speculated on the reasons which led the president to reject the nominations. In fact, some of the nominees are far from uncontroversial. One judge was prominently accused of bribery, another judge controversially dismissed a collective law suit against the financial services provider Amber Gold (which was liquidated following the discovery that is was based on a pyramid scheme), and a third was involved in the widely discussed case of restricting the “parents’ rights” of a couple accused of violence against their children. In addition, one judge was widely criticised for continuously extending the arrest of a football fan for alleged drug-dealing, yet without any verdict being issued over the course of three and a half years. Last, one of the judges whose promotion was denied judged on a case in which Law and Justice party Jaroslaw Kaczynski leader sued fellow legislator Janusz Palikot (then Civic Platform, later founder of ‘Palikot’s Movement’) for insulting him.

None of the above-mentioned controversies would generally justify denial of appointment or other presidential intervention. Thus, it is more likely that they are part of the Law and Justice government’s plan to reform and mould the judiciary in their image. Given that Duda is generally seen as little more than a vicarious agent of Law and Justice leader and Polish politics’ grey eminence (he does not hold any government office) Jaroslaw Kaczynski, it is not unreasonable to assume that the president is now helping to fulfil that plan (while at the same time extending the powers of his office). In a recent proposal made by the government (which was already widely criticised by the Human Rights Ombudsman and NGOs), the National Judiciary Council would have to propose two candidates per vacancy thus considerably increasing the president’s power over judicial nominations. This, together with the conflict over the constitutional court and the government’s decision to once again merge the position of general prosecutor with the minister of justice (the positions were separated by the predecessor government in 2008 and unsuccessfully vetoed by president Lech Kaczynski) highlights the great importance that Law and Justice attaches to judicial reform. Nevertheless, it also shows that judicial independence in Poland might increasingly come under threat – not only, but partially due to president Duda’s activism.

Please note: Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of UCL, SSEES or UCL SSEES Research Blog

Close

Close