Eastern Europe: how to be a pessoptimist

By Sean L Hanley, on 15 December 2019

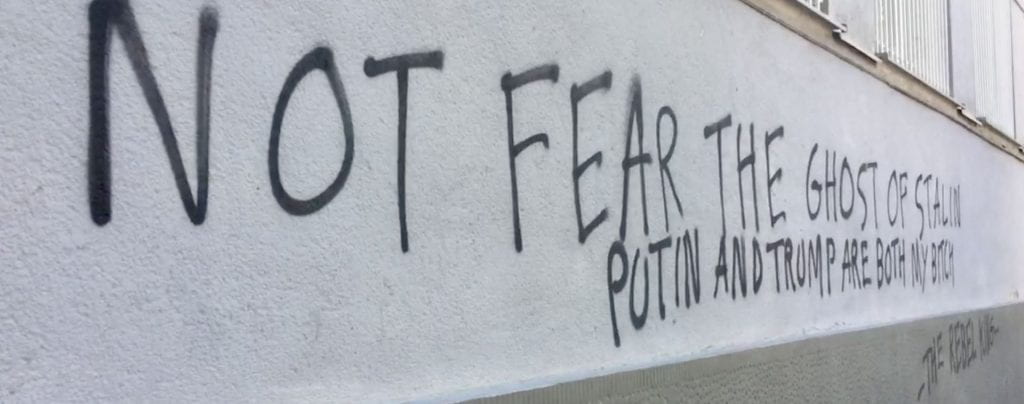

Photo: Martin2035 [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Three decades after the fall of communism, Eastern Europe’s democratic development is seen in increasingly gloomy terms. However, we may need to find a more pragmatic, middle way in assessing the region, argues Seán Hanley.

The region termed Central Europe or Central and Eastern Europe – the body of small and medium-sized states between the former USSR and the established democracies of Western Europe – was once seen as the great success story of post-communist democratisation: rapid and peaceful political transition in 1989-90; a quick return to economic growth; flawed but functional liberal democracy; relatively rapid integration into the EU; political elites who seemed, whether out of conviction or pragmatism, willing and able to imitate West European political, economic and ideological models – although these were (and are) diverse, ranging from Nordic style welfare capitalism to British-style deregulation and neo-liberalism.

Since mid-2000s, however, the intellectual climate among both commentators and political scientists the agenda has shifted from one of understanding consolidation, integration and consolidation or remedying the flaws of stable, but weakly performing post-communist democracy to one of deep gloom.

Now, compared to early hopes of the liberal project, the narrative has become a pessimistic one. Of democratic decline or even backsliding toward authoritarianism. The rejection by voters and elites in Central and Eastern Europe of Western European models – and the EU status quo – as too socially and economically political for their traditions and societies. And of constitutional liberalism as constraining the democratic will of the people, or holding back the emergence of a capable modernising state. Economic catch-up with Western Europe, especially in terms of the living standards of poorer, older, less educated, seems a chimera.

Populist critics now decry the locking in of Central and Eastern Europe as, once again, an exploited peripheral Europe (including Mediterranean democracies of Southern Europe and the Balkans) – analogous, but on a much bigger scale to the “left behind” marginalised regions within Western European countries, which have fuelled populist electoral insurgencies.

Given ineffective and cumbersome procedures for enforcing the rule-of-law – in what was supposed to a club of liberal-democratic nations – the EU, as R. Daniel Kelemen has suggested, is becoming a patchwork of regimes encompassing democracies, semi-democracies and downright authoritarian states, hamstrung by North-South and East-West splits.

What is especially jarring is that some of the supposed frontrunners democratisation in the region – Hungary and Poland – are now the vanguard of “democratic backsliding”, conservative counter-revolution and experiments in liberal governance. Some prominent governance indices, such as Freedom House’s ‘Freedom In the World’, now classify Hungary as having slipped below out of the zone of fully liberal democratic ‘Free’ societies. Poland is rapidly heading the same way.

Worse still, some of the treasured mechanisms of building democracy such as civil society development and grassroots activism have turned out work in ways quite opposite to that envisaged in 1990s. In Hungary and Poland, the electoral breakthroughs of the Fidesz and Law and Justice (PiS) parties were prefigured years before through the development of networks of conservative civil organisations and right-wing civic initiative at grassroots level.

Moreover, the main vehicles for illiberalism have not been ‘red-brown’ alliances of ex-communists and fringe nationalists, but parties and politicians with often impeccable roots in the anti-communist opposition, accepted by West European centre-right as mainstream conservative parties and political allies.

That said, there are many varieties of populism and democratic decline, ranging from the conservative electoral revolutions of Hungary and Poland, to the longstanding weak, but oddly stable corrupt democracies of Bulgaria and Romania, to the fragmented and feverish political landscapes of Slovakia and Czechia – and the strange “technocratic populism” of Czechia’s billionaire prime minister Andrej Babiš ,who still unsure if he wants to be the Czech Macron or the Czech Trump.

George Orwell’s dictum that “All revolutions are failures, but they are not the same failure” is, unsurprisingly, often quoted these days in relation to East Europe. We could also paraphrase Tolstoy and say that all unhappy democracies are unhappy in their own way. Or we might remember the historians Joseph Rothchild and Nancy M. Wingfield’s characterisation of the region – made originally after the decline and fall of communism in late 1980s – about Eastern Europe’s “return to diversity”.

The ‘what went wrong’ debate?

There has been extensive and ongoing debate about “what went wrong in Eastern Europe” and what explains its various forms of illiberalism and democratic decline. A variety of explanations for this have been advanced, some contradictory, some overlapping:

- Some say that the waning of EU leverage after enlargement in 2004-7 gave free rein to voters and politicians with weak democratic commitments; others that under the tutelage of EU, the region had too much top-down liberalism – especially too much economic liberalism – and not enough scope to find its own way;

- Ivan Krastev and Steven Holmes wrote eloquently about the cultural and socio-psychological strains of a “politics of imitation” and of the fading attractiveness of West European models after the 2008-9 recession, the Eurozone crisis and refugee crisis;

- SSEES’s Jan Kubik wrote of a “delayed transition fatigue” in which the cultural and psychological trauma of the initial post-communist reform has finally only recently made itself fully felt;

- Still others highlight the insufficiency of economic growth and the engrained value divide between Western and Eastern Europe, the lack of sizeable or wealthy enough middle class in the region, and the exit of youngest and best educated citizens for opportunities abroad.

In other ways, however, the “what went wrong debate” is mis-framed. Outcomes in Central and Eastern Europe have certainly turned differently from what was expected. But this tells us that intellectuals and social scientists have yet again gone wrong in their expectations, more than that the region has sharply changed course.

And, especially in the context of Eastern Europe and the former communist world, such failures of anticipation not should surprise us. Political scientists studying Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were generally blindsided by the speed and scope of the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the subsequent break-up of USSR. Many then confidently anticipated the rapid breakdown of democracy in Eastern Europe based on misleading analogies with Latin America.

Transition Eastwards?

Photo: Justin.li Around the world via photopin (license)

It is therefore tempting to wonder if, in some senses, nothing has gone wrong. Indeed, Central and East European countries’ political travails might indeed show just how successfully Westernised they have become.

That they have become “normal countries” not just in the sense that they have had reasonable levels of economic growth and human welfare since 1989, but also politically. Indeed, in some ways Eastern Europe is more “normal” than Western Europe.

While it has often served as a model for other parts of the world – and informed political scientists’ view of the world – the experience of Western Europe is an odd one, as distinct and peculiar in its own way as that of post-communist or post-Soviet East. It is based on a pathway of state- and civil society building democratisation and booming post-war welfare capitalism unlikely to be repeated that is gradually unwinding and eroding. West European political parties, as Stephen Whitefield and Robert Rohrschneider have noted, struggle to bring together diverse, fluid electorates, and when they do manage to do so, manage the trick largely because they can still rely on declining core of voters loyal voters and members; remnants of grassroots mass organisation and bases in civil society; and fading but still persistent historical party identities.

When (and if) the transformation of West European societies into fragmented ‘post-democratic’ societies of apathetic but angry political consumers and indistinguishable elite-based parties dependent on big money and big media – memorably outlined by Colin Crouch – is compete, Western Europe may curiously come to resemble the post-communist East.

While East European politicians have naturally sought the legitimacy conferred by historic West European party labels, paradoxically, Western Europe may increasingly be converging towards Central and Eastern European model of fragmented, fluid electorates; ideologically rootless parties; and pragmatic managerial politicians, whose hold on power is disturbed only by periodic populist upsurges at the polls.

And there are direct impacts: the export of some aspects of “political technology” from the post-Soviet space to the West through figures consultants Paul Manafort; Western conservatives’ and populists’ fascination with Viktor Orbán as a trailblazer of illiberal governance; but also the influence of pro-European, civic protests in Bratislava, Prague or Bucharest, self-consciously (if inaccurately) echoing the revolutions of 1989, on liberal opinion in West Europe including movements such Britain’s (now flagging) anti-Brexit movement.

Perhaps it is time to reverse the telescope and reflect upon what CEE can tell us about the erosion of historically-based patterns of politics in Western Europe – or at least to bear in mind that in some sense our whole continent is “post-communist” or “post-Soviet”.

How to be a pessoptimist

The Oxford-based political scientist David Runciman has pointed out that debates about liberal democracy have historically veered between overblown optimism and triumphalism, on one hand, and dark pessimism about the sudden death of liberalism on the other – he also speculates that while political authoritarianism is still with us, even in contemporary Europe, where they do emerge, threats to democracy and liberal freedoms are as likely to come from technology, climate change or concentrations of private power, as populist strongmen.

The experience of the last 30 years in Eastern Europe shows us not only how often and how easily political scientists are blindsided by events, but also how stark narratives of progress and regression, democracy and dictatorship, liberalism and illiberalism, disappointments and hopes gloriously fulfilled, capture the reality or the diversity of the region.

As Seymour Martin Lipset suggested – borrowing the term once coined by the Palestinian novelist (and Communist) Emile Habibi – we need to study democratisation and its alternatives in Eastern Europe with a resolute ‘pessoptimism’. A scepticism about whether historical change cuts strongly in any particular direction, but a limited one. A sense that positive and negative change may sometimes be intimately intertwined.

What might this mean today? I think it perhaps means recalibrating our thinking in four overlapping ways:

First, we would do better to think in terms of opened-ended trajectories and directions, rather celebrating or commiserating consolidation or de-consolidation of any one regime with too much certainty.

Countries can move erratically in different directions. Poland, for example, was at the centre of attention in mid-2000s when democratic backsliding in CEE first became a concern as the ‘capital of Central European illiberalism’, but, after the short-lived 2005-7 coalition of populists and conservatives, the country appeared instead a case of non-backsliding, before re-emerging as a prime backslider with the election in 2015 – and controversial judicial and institutional reforms – of the majority conservative-nationalist government of the Law and Justice Party.

Second, we political scientists should be reminded by this that when we do think about political regimes, we need to so to think more in the longer term. Although it is possible that post-1989 economic and political liberalism in Eastern Europe may prove a mere interlude, the evidence suggests that short-term (and even medium term) reversals we see may be more what Charles Tilly sees as part of the ebb and flow of long-term democratisation. Some of the episodes of backsliding which so preoccupy us today may prove short-term and reversible, better seen as illiberal ‘swerves’ or ‘near misses’ on a dangerous and winding road.

Tilly sees democratisation as a complex, long-term contest between rapacious elites and social groups (and not always very liberal) social groups over state power and state resources. It is a perspective well-tuned to studying politics in the post-communist world. And it reminds that even – or perhaps especially – in the most open, decentralised and liberal political systems, democracy is about exercising and balancing power. So, third, we need a robust and unromantic view of what Philippe Schmitter termed “really existing” democracy, West and East, recognising the trade-offs and tensions, and the need to adapt and accommodate some the illiberal realities, which we may not like, but can perhaps learn to live with (social conservatism, populism, oligarchical parties).

In truth, despite the progress of the last thirty years, the social and economic gaps – and perhaps socio-cultural gaps – between Western and Eastern Europe stubbornly refuse to close with any speed. Notions of catch-up, convergence or/and gradual Europeanisation – while useful for framing policy instrument – now look dated now look as political projects. This, finally, leaves the difficult task of making Eastern Europe better, freer and more self-confident periphery. Conservative nationalist and illiberal populists in the region have alteady understood and embraced the search for alternatives with alacrity.

This is an edited version of a presentation given at the “1989 – Great Expectations 30 years later” conference organised by the European Dialogue Expert Group and the Gorbachev Foundation, Moscow, 9 December 2019.

Seán Hanley is Associate Professor in Comparative Central and East European Politics at UCL-SSEES.

Close

Close