What is happening in the Donbas? An overview of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict

By sarah.moore.19, on 8 March 2022

Given the worrying escalation of tensions between Russia and Ukraine, Slovo feels that the time is right to create a blog post discussing the conflict so that our readers can learn more about the events taking place there currently. Qianrui Hu is one of our General Editors and a first-year PhD student researching the dynamics of identities in the context of the ongoing war in the Donbas, so he was perfect to sit down for a chat with our Online Editor, Sarah Moore, to discuss all things related to the conflict, from its origins to the potential implications for the wider international community.

Please note that this interview took place before the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, and was originally intended to be an overview of the conflict in the Donbas. However, Slovo feels it is important that this blog post should be amended as much as possible to include recent developments. All information is accurate at the time of writing, but we recognise that certain elements may be outdated at the time of posting due to the escalation of conflict.

Q: What is currently happening in the Donbas?

A: Since the war broke out in 2014, Donbas has undergone fierce battles between Ukrainian government armies and separatists backed by Russia. There are also numerous evidence indicating Russia’s direct involvement in the war. To date, there have been two peace agreements; Minsk agreement I and II. Since the September of 2015, the situation in Donbas is relatively calm, although sporadic shootings happen frequently. As a result of the war, the Donbas region is split into two parts: Ukrainian government-controlled areas and two self-proclaimed republics, namely DNR and LNR, whose sovereignty is not recognized even by Russia. Russia has been continuously framing the war in Donbas as a civil war between local armed groups and Kyiv, but many western scholars refrain from calling it a civil war, as the Russian involvement and local manipulative elites (including the biggest oligarch in Ukraine, Rinat Akhmetov) are the key to the escalation and sustaining of the conflict. Tragically, the ongoing war has claimed 14,000 lives, and more than 1.8 million people became internally displaced persons with another 1 million fleeing to other countries, predominantly to Russia.

Q: What is the history behind the conflict?

A: The history regarding this region is very complicated. According to the Ukrainian version of history, the Donbas should be part of the modern Ukrainian state because it is an integral part of Ukrainian ethnographic territory and Ukrainians’ historical patrimony. However, unignorably, from the eighteenth century onwards, the region was undergoing a huge influx of migrants as a result of Tsarist immigration policy. At the same time, many Ukrainian peasants were encouraged to move to the Urals and Siberia especially after the 1861 emancipation reform. Also, in 1764, a new administrative concept called Novorossia (‘New Russia’) was created, covering South and East Ukraine including Donbas. Subsequently, amid all the turmoil during the first world war, there was a short-lived republic established in Donbas and surrounding regions called the Donets’k-Kryvyi Rih republic. The republic was created in opposition to Kyiv-based Ukrainian People’s Republic as it refuses any forms of Ukrainian nationalism, but the republic was highly dependent on Bolsheviks and hence its legitimacy is controversial. During the Soviet era, the Donbas region again underwent massive influx of migrants, predominantly Russians, and the extensive urbanisation and industrialisation in the region made local residents possess a identity of “imagined economy”. As the industrial output was so high, no wonder there were some well-known slogans such as “Donbas feeds the whole Soviet Union” and later “Donbas feeds the whole Ukraine”. However, the region’s economy started to decline after the Ukraine’s independence. By 2014, it was not a region which could “feed” the whole Ukraine anymore but had to receive additional financial helps from Kyiv.

Q: How did the conflict originate?

A: The conflict in Donbas started with protests. To everyone’s surprise, the former Ukrainian president Yanukovych fled to Russia on 22 February 2014 as a response of the massive protest in the central square of Kyiv, called Euromaidan. Yanukovych was a Donbas-born and was backed up by many residents and local elites. His ousting and the overt Ukraine’s turn to Europe made local residents uncertain about the future, particularly the economic prospects as the region’s economy was highly dependent on Russia. Following the unrest in Crimea, there were also many protests in Donbas condemning the unlawful ousting of Yanukovych in February and March. However, many protesters were actually from nearby Russian regions, and they were bussed to various Donbas cities to take participate in the protests. Also, we do not how many of the protesters were paid to protest by local elites, including the biggest oligarch in Ukraine, Rinat Akhmetov. In April, the social movement in Donbas became radicalized, with various governmental building seized and the creation of so-called Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, covering the territory of Donetsk and Luhansk oblast’ respectively. There were many “volunteers” from Russia who took participate in the battles between Ukrainian government armies and local separatists. Ukrainian government armies managed to take back some of the lost territories, but the two regional centres, Donetsk and Luhansk are still under separatists’ control.

Q: Why is this conflict important with regards to international relations and global peace?

A: Since Ukraine may potentially gain NATO membership, the conflict is crucial for international relations and global peace. Ukraine has become the frontline of the Russia-NATO’s rivalry, and the occupied territories of Ukraine mean Ukraine’s path towards NATO and EU membership is still uncertain. Also, as in any other conflict, there are a huge flow of displaced people and numerous human rights abuses inflicted by the Donbas conflict. The shooting down of a Malaysia Airlines civil aircraft likewise means the conflict is never far away from us and can have a huge impact on us at any minute.

Q: What sparked your interest in researching this topic?

A: I was really interested in the complexity of identity regarding the Donbas region and the conflict. There are so many layers in this issue and I genuinely wish to hear first-hand accounts from local people themselves. I am a massive fan of Svetlana Alexievich and I really hope to incorporate her style of writing and investigating into my research.

Q: What is your current research based on?

A: My research is looking at the fluid identity of people with dual nationality in Donbas in the context of the ongoing war. As a result of the massive migrant flow into Donbas, intermarriage was so common in the area. According to official statistics, the intermarriage rate reached 55% in 1970s, meaning there is an enormous number of people who actually possess more than one ethnicity. However, in the first and only one census of the modern Ukraine, they were not given a choice in the census to claim their true identity, as they had to choose either “Ukrainian” or “Russian”. Shall we assume these people naturally possess a middle-ground identity? This is unlikely because there are so many other factors which can affect an individual’s identity, just as we learned from our sociology textbook. My research, hence, is eager to examine the interactions of ethnic, regional, and national identity and the casual mechanisms of how various factors and lived experience influence the context of their identity and the process of their identification, using the case of people with dual nationality.

Q: Why do we (those interested in the SSEES region and the wider academic community) need to know about the conflict?

A: As I have been trying my best to illustrate the origins of this conflict here, the Donbas case is just so fascinating and there are just so many things to study about from different perspective! Whether you are a political scientist, sociologist, or psychologist, the empirical evidence is so rich in the Donbas case. Also, except from those war entrepreneurs who can gain colossal benefits from wars, every conflict is a tragedy for everyone else. My humble wish is by studying the conflict onsets and dynamics, I can make the smallest contribution to future conflict prevention and alleviate a tiny bit of the pain of those who suffered from the war.

Q: How has the international community responded to the escalation of tensions in the region?

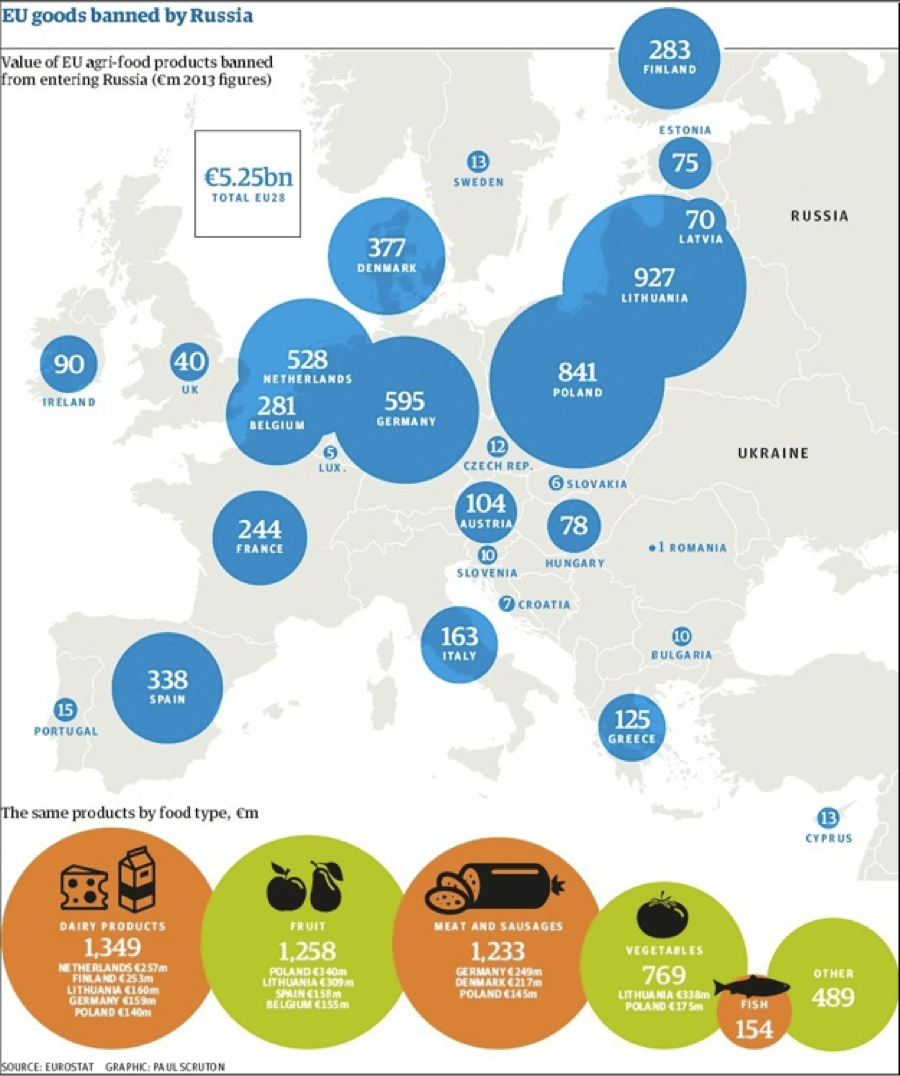

A: On 21 February 2022, Russia recognized Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, but Putin did not specify whether Russia recognizes the de-facto borders of these two republics, or the borders claimed by these two republics, that is the whole territory of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti. The recognition of these two republics was followed by an infamous speech of Putin, in which he again denied the legitimacy of Ukraine as a country and believed Ukrainian as a nation is an artificial concept. Since his speech did not only touch upon the two republics, but Ukraine as a whole, many people were worried that Putin is aiming for expanding the borders and capturing more territories in Ukraine. The next day Putin confirmed that Russia recognizes the borders of the two republics as the borders articulated in the constitutions of the republics, which clearly shows Russia is going to expand borders. However, the Russia’s invasion in Ukraine on 24 February 2022 at 5 am still shook the whole world, as it is totally unprovoked, and Russia attacked the whole territory of Ukraine. In a video address aiming to justify the invasion, Putin mentioned the goal of this “special military operation” is to demilitarise and de-Nazify Ukraine. The barbaric attack on Ukraine was responded by harsh sanctions of the international community. Russia is sanctioned financially in all possible ways including the expulsion of some major Russian banks from SWIFT. The war is still unfolding, but it is clear that Russia has failed its initial goal of blitzkrieg. Russian armies are faced with strong resistance from both Ukrainian militaries and civilians. Hence, unfortunately, we can see Russia has somehow adjusted its plan to a more brutal way and we are witnessing more and more casualties of civilians. These horrendous war crimes must be recorded and stridently punished later by the international community.

Glory to Ukraine!

Slovo wishes to convey its shock and anger at the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and lends its full support and sympathies to all involved in the conflict. We also encourage you to get involved, whether it be attending protest demonstrations or donating items for those in need. A full list of ways you can get involved can be found on UCL’s ‘Ways to Help’ webpage.

Close

Close