The Irony of Fate (or Enjoy Your Bath!) – The Quintessential Soviet New Year Film

By serian.carlyle.14, on 31 December 2020

On this strange New Year’s Eve, the Slovo team invite you to read this review of the quintessential Soviet New Year’s Eve film, a film that remains a staple for many Russian households on the 31st. In her review, Lara Olszowska explores the role of architecture as an ideological signifier in the film. If you’ve seen the film, we’d love you to share your thoughts in the comments below or on Facebook and Twitter using the hashtag #SlovoSuggestions. Until then, Happy New Year!

Film, 184 min

Directed by Eldar Ryazanov

Written by Emil Braginsky, Eldar Ryazanov

Produced by Evgeny Golynsky

Soviet Union, 1976

Language: Russian

“Совершенно нетипичная история, которая могла произойти только и исключительно в новогоднюю ночь”

“A completely atypical story that could happen only and exclusively on New Year’s Eve”

–Eldar Ryazanov, Irony of Fate

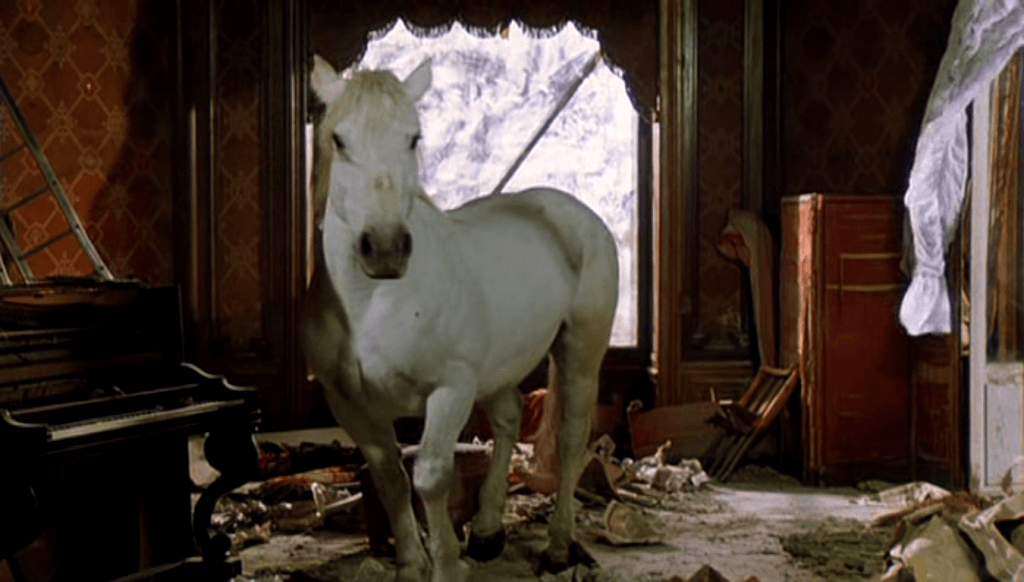

On New Year’s Day 1976, Eldar Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate or Enjoy Your Bath! was first broadcast to television audiences across the Soviet Union. The epigraph attributes the ludicrous events that unfold to the date on which they occur, whilst the second title highlights the initiator of the action as the bathhouse. It later becomes apparent that the true driving force behind the plot is something far less magical than New Year’s Eve and even more ordinary than a festive drinking session at a bathhouse with friends. It is the typical setting in which this “atypical story” is told: a standardized Soviet apartment in an archetypal mikroraion, or suburb. This review posits the role of architecture as an ideological signifier in the film.

Zhenya Lukashin lives in apartment 12, 25 Third Builder’s Street, Moscow. So does Nadia Sheveluova, but in Leningrad. Once Zhenya enjoys his bath and too much vodka, he mistakenly flies to Leningrad, gives his address to a taxi driver, lets himself into Nadia’s flat using his key, and falls asleep in her bed. After she stirs him from his stupor, the pair spend a farcical evening together and eventually fall in love. The irony of their fate is that their chance romance is a result of Soviet residential planning; a dreary housing block can become the locus of a New Year’s Eve miracle. One of the final lines in the film is Zhenya’s: “Fate brought me to Leningrad and in Leningrad there is a certain street, with exactly the same housing block and apartment, without which I would never be happy”. In other words, he thanks the city for Nadia, not New Year’s Eve for his newfound happiness. Ironically, his destiny as a Soviet man to live in an unremarkable mikroraion with any wife (he manages to substitute his fiancée for Nadia almost seamlessly) remains unchanged no matter how much of an “adventure seeker” Ippolit (Nadia’s fiancé) considers him to be. The conventional fairytale ending neatly upholds traditional Soviet values of domesticity and glosses over the deeper levels of conflict within soviet housing.

The cartoon that preludes Irony of Fate makes a visual mockery of Soviet architecture and marks the film’s raison d’être: two matching flats in identical housing blocks, both with identical addresses, both in identical mikroraiony and each inhabited by the two lead protagonists. The animated architect seeks approval for his imperial-style buildings from bureaucrats, who reject the designs until every decorative feature has disappeared from the façade leaving the prototypical Soviet housing block behind. The newly approved rectangular block shown in the cartoon has nothing “new” about it. As viewers were aware, the only choice for architects was to build according to the model that aligned with the regime. By the 1970s Khrushchev’s prefabricated housing had been reproduced so many times with so little innovation, it demonstrated the absurdity of Soviet planning and the inescapable influence of socialist ideology. The character’s inability to escape the army of apartment blocks that chase him in this opening sequence shows his personal resistance to the regime, personified by a marching mikroraion. The need to present the mikroraion as such a caricature reveals how the ubiquitous ideological signs of the Soviet period were and how desensitised citizens had become to them.

In his light-hearted deprecation of soviet planning, Ryazanov alludes to a heavier criticism of socialist byt, or living. The undisputed aim of socialism was to build a new society from scratch. Housing to induce socialist byt was therefore ideology materialised. The new Soviet person would live in and be conditioned by the new socialist city and form a collective of like-minded individuals, their individuality suppressed by the state. As the voiceover sarcastically narrates: “a person can come to an unknown city and feel at home there” because they are all familiar and all the same. In the film, the uniformity of the suburbs do not generate social harmony as intended, but instead cause chaos for the protagonists. The verisimilitudinous Soviet architecture in the film held a mirror to the Soviet viewer on that New Year’s Day in 1976, likely watching from the comfort of their prefabricated home, reminding them of the ideological project their houses were constructed to complete and how that project remained unfulfilled. There lies the true irony beneath the surface of the lovers’ luck: the irony of socialism.

Review by Lara Olszowska, Masters Student at UCL SSEES

Close

Close