The Slade Session, and Beyond

By Slade Archive Project, on 5 February 2016

Guest post by Dr Amara Thornton, British Academy Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Institute of Archaeology, UCL

The Slade School of Fine Art has a world famous reputation as a venerable art training institution. I’m currently investigating two early Slade artists who made a lasting contribution to archaeology: Jessie Mothersole and Freda Hansard. I’ve been reading Transnational Slade articles and realised that the experiences of these two women feed into this theme, providing an early example of the School’s international impact, links between different fields of study, and the role of UCL (and the Slade in particular) in providing opportunities for women.

As part of my research I’ve examined UCL’s Session Fees books, a rich resource for disciplinary and institutional history at UCL. These books record payments of students’ fees over the course of an academic year (session), extending from October to June, and provide an intriguing snapshot of the student body in each UCL Department at a particular moment in time. UCL admitted both male and female students from the 1870s onwards. Jessie Mothersole (1874-1958) was a 17-year-old from Colchester when she entered the Slade for the 1891-1892 session, remaining until 1896.

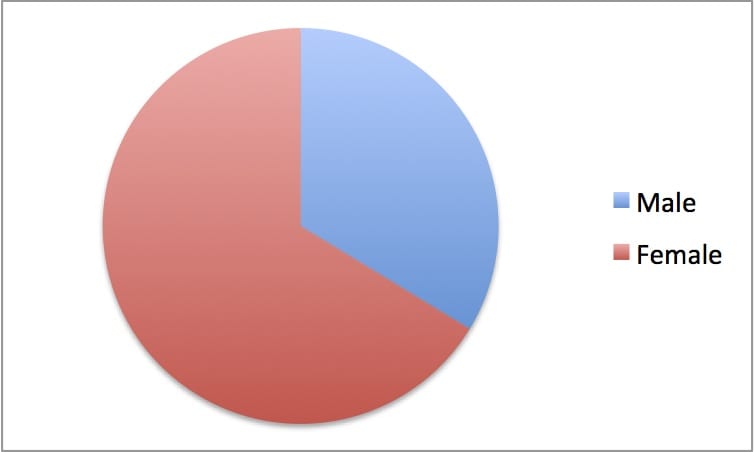

She joined a significant number of women students taking classes at the Slade at that time. A quick gender analysis of the Slade students listed in the 1892-1893 session looks like this:

Jessie Mothersole’s artistic skill did not go unnoticed; she was awarded prizes (2nd class) in drawing from life and drawing from the antique in 1892. In 1893 she was awarded certificates in advanced antique drawing and figure drawing. These awards foreshadowed her career in illustration and writing.

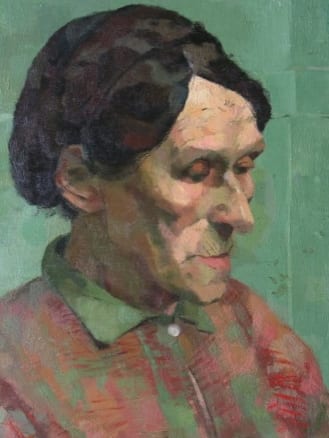

Winifred “Freda” Hansard (1872-1937) studied at the Royal Academy Schools before she entered the Slade for the 1895-1896 session, remaining until 1897. Her work was later included in the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. In 1899 she exhibited Isola dei Pescatori in Lago Maggiore and Medusa Turning a Shepherd into Stone, which was described in Hearth and Home as “a vigorous, dramatic picture…”. Her painting Priscilla was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1900 and Rival Charms in 1901.

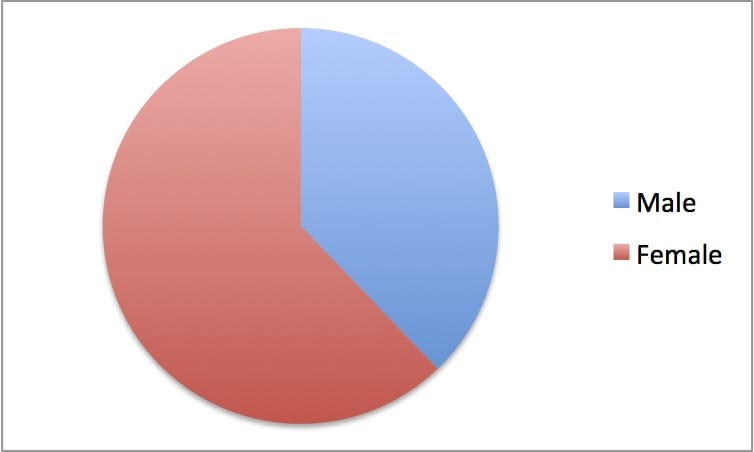

In 1902 Freda re-entered UCL as a student in Egyptology under the leadership of Professor Flinders Petrie. As in the Slade a decade earlier, in the 1902-1903 session, the number of women Egyptology students surpassed that of men.

At this point Petrie was making annual journeys to Egypt to excavate ancient sites. Egyptology students were offered the opportunity to take part in Petrie’s excavations, and in 1902 Freda Hansard joined eight other team members at Abydos, a town and pilgrimage site north of Luxor. There her artistic skills were harnessed to record the inscriptions and scenes on the walls of the Osirieon, a special building for the worship of the Egyptian god Osiris, ruler of the Underworld.

The drawings she made with Egyptologist and UCL lecturer Margaret Murray, who directed the Osereion excavations with Petrie’s wife Hilda, were put on display at UCL alongside antiquities from Abydos in July 1903. Hansard returned to Egypt for the 1903/1904 season, joining Jessie Mothersole and Margaret Murray at the cemetery site of Saqqara – an hour’s train and then another hour’s donkey ride away from Cairo.

Jessie Mothersole used her camera to capture the setting of this transnational phase in her artistic life. Her photographs show the Saqqara landscape, ancient remains, excavation scenes and the Egyptian team working with them. These images were later published in an article entitled “Tomb Copying in Egypt” for the popular magazine Sunday at Home. The publication included two uncredited line drawings, probably done by Jessie herself, depicting the hut in which she, Freda and Margaret Murray lived on site and the Egyptian boy who brought them water every day.

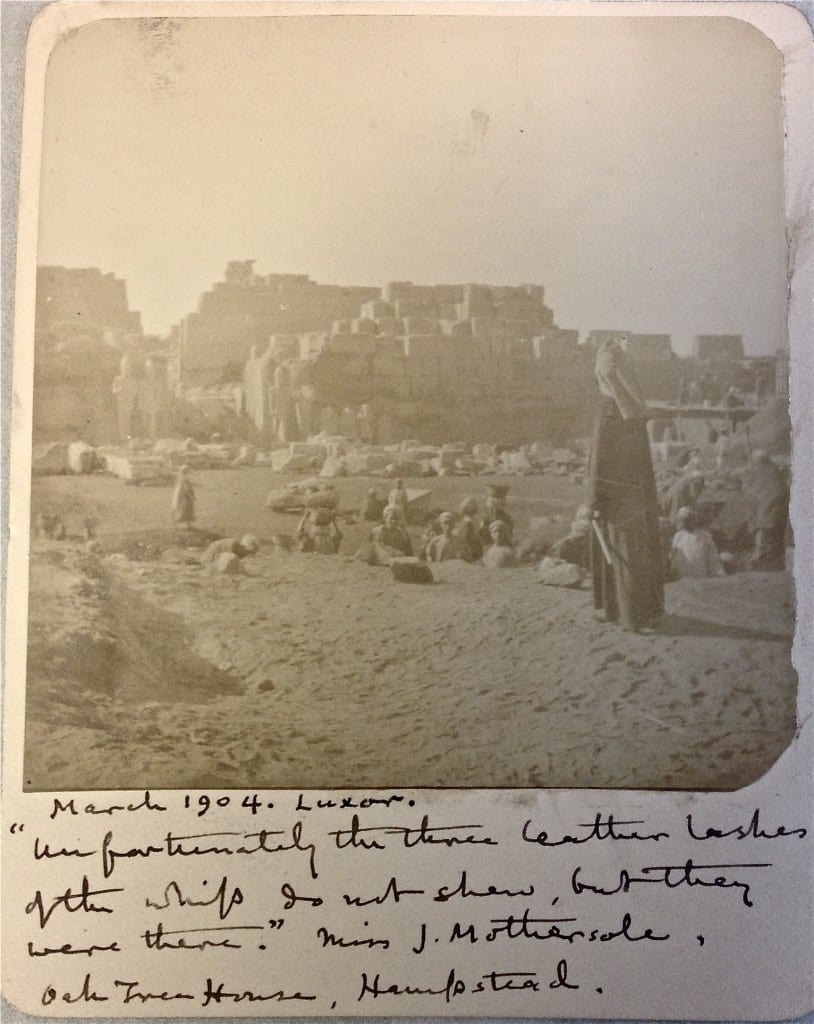

The Petrie Museum has one photograph in their archive credited to Jessie Mothersole, taken in Luxor rather than Saqqara (fig 3). But the hand-written caption underneath hints at her eye for minute detail that permeates her article.

Fig. 3 This photograph is dated March, 1904. Its handwritten caption reads: “Unfortunately the three leather lashes of the whip do not show, but they were there.” Miss J. Mothersole, Oak Tree House, Hampstead. Courtesy of the Petrie Museum of Egyptology.

Jessie remained largely based in the UK thereafter, moving into book illustration and writing on British archaeology. Freda returned to Egypt for further work at Saqqara, and married former solicitor turned Egyptologist Cecil Firth in 1906. The Firths were mainly based in Egypt, barring the period of the First World War, and Freda Firth continued to contribute to archaeological illustration after her marriage. Excerpts published from her daughter Diana Firth Woolner’s 1926 diary reveal something of the Firths’ life in Egypt and the Anglo-American-Egyptian network at work. One particularly interesting entry describes Freda and Diana’s visit with artist/archaeologist (and former UCL Egyptology student) Annie Pirie Quibell to see Egyptian bread being made.

Freda Firth took advantage of the opportunities at UCL for intellectual expansion as a woman student and built a life for herself in Egypt. Her experiences there coloured the rest of her life as an artist, and give her a lasting transnational legacy. She and Jessie Mothersole were two of many women whose time at UCL affected the rest of their lives. I was happy to discover recently that this history is currently being explored through a new arts project – Kristina Clackson Bonnington’s The Girl at the Door. I think Jessie and Freda would approve.

References/Further Reading

Bierbrier, M. 2012. FIRTH, Winifred (Freda) Nest (nee Hansard) (1872-1937). Who Was Who in Egyptology 4th Revised Edition. pp. 191. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Graves, A. 1905. The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol III. Eadie to Harraden. London: Henry Graves and Co. Ltd/George Bell & Sons.

Harte, N. & North, J. 2004. The World of UCL 1828-2004. London: UCL Press.

James, T. G. H. 1994. The Other Side of Archaeology: Saqqara in 1926. Egyptian Archaeology 5: 36-37.

James, T. G. H. 1995. The Other Side of Archaeology: Saqqara in 1926 (II). Egyptian Archaeology 7: 35-37.

Mothersole, J. 1908. Tomb Copying in Egypt. Sunday at Home. February. (pp. 345-351)

Murray, M. 1903. The Osireion at Abydos. London: Bernard Quaritch.

Murray, M. 1963. My First Hundred Years. London: William Kimber.

Thornton, A. 2015. Exhibition Season: Annual Archaeological Exhibitions in London, 1880s-1930s. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 25 (2): 1-18; Appendices 1 (pp. 1-5) and 2 (pp. 1-44). DOI: 10.5334/bha.252.

UCL Calendars for 1893, 1894 (UCL Records Office).

UCL Session Fees Books, 1892-1893, 1902-1903 (UCL Records Office).

With thanks to Alice Stevenson and Robert Winckworth.

Close

Close