Transnational Slade: Ibrahim El-Salahi

By Slade Archive Project, on 17 June 2014

Ibrahim El-Salahi

The third contribution in a series of guest posts by Amna Malik

The Transnational Slade project is interested in the links between past students at the Slade and the impact they went on to have internationally after graduation.

Ibrahim El-Salahi was widely known in the emergence of African modernism in the 1960s but his work has been seen only recently in the UK. His importance is evident in the quote below from Professor Salah Hassan:

‘El-Salahi’s accomplishments offer profound possibilities for both interrogating and repositioning African modernism in the context of modernity as a universal idea, one in which African history is part and parcel of world history. El-Salahi has been remarkable for his creative and intellectual thought, and his rare body of work, innovative visual vocabulary, and spectacular style have combined to shape African modernism in the visual arts in a powerful way. His contributions, while distinctive and unique, show striking resemblances to those pioneer African modernists such as Skunder Boghossian, Dumile Feni, Ernest Mancoba, Gerard Sokoto, Malangatana Ngwenya, and other important figures whose decade-long journeys have transformed visual art in Africa. Like several of those artists, he has also had his share of an itinerant life, which has significantly molded his career.’ Salah Hassan, ‘Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism’ p11.

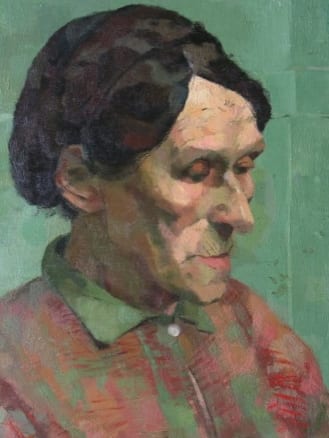

Fig1. Ibrahim El-Salahi

‘Portrait of a Woman from Egypt’, 1950-54

Oil on canvas, 31.5 x 38cm

Collection Eve El-Salahi

El-Salahi came to London from Khartoum to undertake the Diploma course in Fine Art between 1954 and 1957. Born in 1930 in Obdurman, Sudan, El-Salahi was taught by British colonial artists in the School of Design between 1949-51 at Gordon Memorial College, majoring in painting. His initial introduction to western empirical approaches to art can be seen in two portraits Portrait of a Woman From Egypt (fig. 1) and Portrait of a Young Man (fig. 2) both are dated 1950-54, the years prior to his arrival at the Slade. They are confident, vibrant paintings indicating a youthful vitality, but are also clear demonstrations of his ability to master empirical methods. This was a good grounding for his later years at the Slade, where drawing from the life-model was essential to passing exams. In some ways a residue of an academic style of art education that had been eclipsed in Europe and the US by the more experimental approaches inaugurated by the Bauhaus and the rupture of modernism with nineteenth-century academic traditions of art making. However, that academic style had flourished in the emergence of new national art colleges in the 1920s and 1930s in the countries that had been previously subsumed under the old Ottoman empire: Iraq, Syria, Jordan, and in newly emerging independent nation states of Egypt and Lebanon. In that respect, El-Salahi’s knowledge of painting and drawing from the model was not new but a well established set of techniques.

At the Slade this knowledge was furthered by contact with eminent art historians such as E.H Gombrich whose best-selling The Story of Art was the set reading for the students. Gombrich’s lectures were premised on the analysis of perception, how the eye sees and interprets objects in the external world, and how this enters into the practice of Renaissance artists.

Fig. 2. Ibrahim El-Salahi

‘Portrait of a Young Man’, 1950-54

Oil on paper, 14 7/8 x 12″

Collection of Eve El-Salahi

In this respect, El-Salahi’s work developed with considerable sophistication evident in the difference between the more linear approach to his early portraits and the abandonment of line in favour of subtle tonal modulations in a work such as Portrait of a Model (1956) (fig 3). The study of light on the face is given much greater attention as to convince the spectator that the work was made with the model seated before the artist. The weightiness of her corporeality and the contingent and transitory shift of light mark it out as a more mature study. El-Salahi’s subsequent move towards calligraphy that would later mark his pioneering development towards African modernism was fostered to some degree by his regular visits to the British Museum.

Fig. 3. Ibrahim El-Salahi

‘Figure’ (female model), 1956, Slade period

Oil on plywood board, 42.5 x 57.5cm,

Collection of Eve El-Salahi

In addition to the compulsory courses in anatomy and life drawing supplemented by art historical lectures on perception, the Slade curriculum in the 1950s also included design-based courses in lettering, in which El-Salahi excelled. Important works by him that indicate the transition from an empirical based approach to the world to one that moved increasingly towards abstraction, can be found in a painting like Church on the Hill (1956) (fig 4), a landscape painting composed largely of evenly regulated surfaces of colour, many in different tones of green, with the contrasting pinks of a terracotta or brick surface of buildings. The overall impression is closer to the grid-like structures of early Mondrian paintings but the influence of Cézanne appears to be more evident in the work.

Fig 4. Ibrahim El-Salahi, ‘Church on the Hill’, 1956,

oil on canvas, 19 ¼ x 22 7/8″ inches

Collection of Eve El-Salahi

A similar approach can be found in his painting Head (1956)(fig.5), a portrait of an elderly suited man in profile. The careful modulation of tones to denote the capturing of the model in light is pushed further so that the patches of different tones become larger and begin to break up the forms. In some respects, these points of tension between figuration and abstraction can be found in the work of artists like Matisse, Franz Macke and Ludwig Kirchner. In El-Salahi’s paintings the distortions of colour and form are reigned in but we can see indications of the later abstract paintings of the 1960s in the fragmentation of the body and surface patterns and structures that were partly created by his immersion into calligraphy.

Please tell us if you know any more of El-Salahi’s years while he was at the Slade or his early years as an artist in Khartoum in the 1950s. We’re looking for a variety of material: photographs, stories about him, letters from him if you have them and are willing to share them, any knowledge of exhibition catalogues from his early period of the 1950s or where we might get them? Please do share your memories of him as a teacher and colleague. Comments can be added publicly through the Slade Class Photos website, or write to: slade.enquiries@ucl.ac.uk or Slade Archive Project, Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT.

One Response to “Transnational Slade: Ibrahim El-Salahi”

- 1

Close

Close

New on the @SladeArchive Blog: Transnational Slade: Ibrahim El-Salahi http://t.co/oxLsnWCsaC #arthistory