A Colour A Day: Week 33

By Ruth Siddall, on 8 November 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 33. 2nd-8th November

Jo Volley writes… This week we have more food colourants accompanied by the first stanza of John Keats’ (1795-1821) poem To Autumn.

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

Colours read from top to bottom:

Blueberry

Rosemary

Forget-me-not

Blackcurrant

Lavender

Passion fruit

Grape

A Colour A Day Week 32

By Ruth Siddall, on 1 November 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 32. 26th October – 1st November

Jo Volley writes…

Coloured copper. Bronze…

silver, pewter, nickel, brass.

Aluminium.

(Haiku for S.N.)

Central: Copper – Lefranc Bourgeois Flashe Vinyl Emulsion

Clockwise from top:

Bronze – Lefranc Bourgeois Flashe Vinyl Emulsion

Silver – Lefranc Bourgeois Flashe Vinyl Emulsion

Pewter – Treasure Non Tarnishing Wax

Nickel – Lefranc Bourgeois Flashe Vinyl Emulsion

Brass – PlastiKote Fast Drying Enamel

Aluminium – Schmincke pigment bound in gum Arabic

A Colour A Day: Week 31

By Ruth Siddall, on 25 October 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 31. 19th -25th October

Jo Volley writes…

This week’s colours are manufactured by Ruth Siddall who says of them. ‘Procion MX Dyes – The difference between a dye and a pigment is that a dye is soluble in water and a pigment is insoluble. I am experimenting at the moment to try and find as many ways of making the colourful, organic compounds in dyes into insoluble pigments. These are a series of pigments I made by dyeing a starch with modern Procion MX dyes. I used potato starch as a substrate. I have seen modern dyes such as rhodamine being used in this way, so I thought I’d give it a go. If I’m honest, I’m disappointed with the pale colours produced – quite the opposite of the dyes which were intensely coloured! Chemically, Procion MX dyes are dichlorotriazines, which means they contain a ring-shaped molecule with three nitrogen ions so the formula is C3H3N3 (most ring molecules just have six carbons). In addition there are two chlorine ions attached to this ring and it is these that bond to -OH groups in fibres to produce strong dyes on cloth. Starch has -OH groups, so I had hoped it would work the same way here. There is some colour but it’s not as intense as I had hoped for.’

Each pigment is bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper. They were like no other pigment I have used before – it was rather like trying to paint with clouds – amorphous – the colour just slipping away. According to the American Meteorological Society, amorphous clouds ‘are without any apparent structure at all, as may occur in a whiteout in a thick cloud or fog over a snow surface when one loses any sense of direction – up, down and sideways’

Procion red MX-G

Procion yellow MX-4G

Procion blue MX-2R

Procion yellow MX-3K

Procion turquoise MX-G

Procion composite grey

Procion red – MX-5B

Recipes and Talks

By Ruth Siddall, on 20 October 2020

Here are some link to resources and that people might find useful.

Slade School Pigment Farm Talks

Over the Spring we had a series of lockdown talks to celebrate the Pigment Farm Project; the talks were about dyes, lake pigments and plants in art generally and come from Emma Richardson, Ruth Siddall, Nicholas Laessing, Andreea Ionascu and Lea Collet. You can watch the recordings of the talks here.

Lots of pdfs with recipes and methods for making a range of artists materials and other constructions.

A Colour A Day: Week 30

By Ruth Siddall, on 18 October 2020

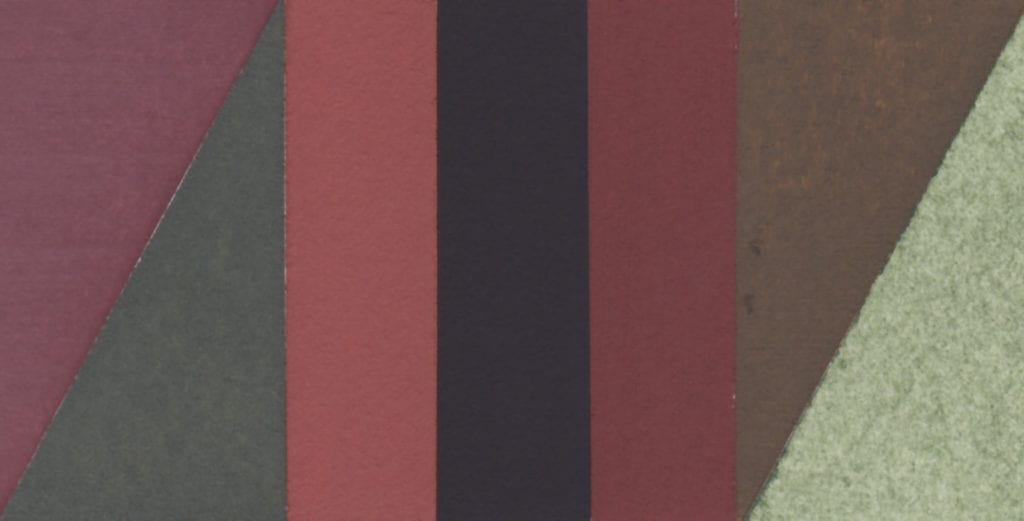

A Colour A Day: Week 30. 12th-18th October.

Jo Volley writes…

In October 2015, whilst on research leave, I travelled around Provence visiting pigment quarries, mines and factories to look at pigment manufacturing methods and processes. In this marvellous red landscape, I have never felt such a strong emotional relationship between the landscape and painting. The trip was also something of a pilgrimage to visit the bibliotheque in Aix en Provence to view a remarkable manuscript made by the C17 Dutch artist A. Boogert who in 1692 completed an educational manual of how to mix every colour available to him. Each pigment is bound in gum Arabic and applied to paper with instruction as to their properties, proportions and potential. It is an extraordinary document of the pigments available at that time and of an artist’s dedication to learning. It was a humbling experience to hold in one’s hands this rare and beautiful manuscript, and to feel a connection with Boogert’s endeavours. The timeless and common manufacture of binding colour and making paint. The sheer pleasure of it… and its desire to communicate. It has also been the inspiration for this project.

Each red earth is bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper.

Collected: Sentier des Ocres, Roussillon.

Purchased: Sentier des Ocres, Roussillon.

Purchased: Sentier des Ocres, Roussillon.

Collected: Les Mines des Bruoux, Gargas.

Collected: Mathieu Ocre Usine, Roussillon.

Purchased: Les Mines des Bruoux, Gargas.

Purchased: Mathieu Ocre Usine, Roussillon.

A Colour A Day: Week 29

By Ruth Siddall, on 11 October 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 29. 5th -11th October

Jo Volley writes…

In the early 1800’s the mineralogist Abraham Werner published the Nomenclature of Colours to identify minerals by key characteristics. It was later amended by Patrick Syme, C19 Scottish flower painter, having been introduced to it by Robert Jameson who had studied for a year under Werner before becoming a professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University. Jameson had matched Werner’s descriptions with the actual minerals, Syme then used these as his starting point for the colour names, descriptions and actual colour charts introducing references to animals and vegetables. Darwin took a copy on the HMS Beagle voyage (1831-1836) and its terminology, ‘lent both precision and lyricism to Darwin’s writings, whether he was detailing the changeable ‘hyacinth red and chestnut brown’ of the cuttlefish, ‘the primrose yellow’ of species of sea hare, or the ‘light auricular purple’ and provided his naturalist contemporaries with clear point of reference, and enabled all his readers to clearly envision the creatures and settings of lands that most, in a pre-photography age, would never see.’

Extracts from Publisher’s notes Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, Natural History Museum

A Colour A Day: Week 28

By Ruth Siddall, on 4 October 2020

A Colour A Day; 28th September – 4th October

Jo Volley writes…

This week’s colours are seven Russian earth pigments gifted by Ruth Siddall who says of them. ‘These seven pigments are supplied by Moscow-based company Colibri Premium Pigments. Many of the earth and mineral pigments they supply are sourced in Russia. This is a selection of their ochres, which include iron ochres (red and yellow ochre) and aluminium-rich earths known as bauxite (deposits much overlooked as ochres). Siderite is iron carbonate. Also included here are two very ‘Russian’ pigments made from minerals mainly known only from deposits in Russia. Shungite is a black, carbon-rich earth pigment. It is found in very ancient, 2 billion year old rocks in Russian Karelia, in the region of Lake Onega. It is named after the town of Shunga. It formed as biogenic deposits, probably from algae preserved in anoxic conditions and then subsequently metamorphosed. Volkonskoite is a green-coloured, chrome-bearing smectite clay mineral. It is sourced from the Okhansk region of the Urals. Tuff is a volcanic ash deposit, in this case coloured purple by iron oxides.

Ruth suggests listening to Sibelius’s Karelian Suite whilst viewing the colours.

All pigments are bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper and read from left to right:

Tuff Purple

Siderite

Mumia Bauxite

Shungite

Sankirnaya Ochre

Volkonskoite

A Colour A Day: Week 27

By Ruth Siddall, on 27 September 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 27; 21st-27th September

Jo Volley writes…

This week’s colours are inspired by Anni Albers’ 1926 wall hanging Black White Yellow exhibited at the Tate show in 2018. In her book, On Weaving, she states; ‘Continuing in our attitude of attentive passiveness, we will also be guided in our choice of color, though here only in part. For our response to color is spontaneous, passionate, and personal, and only in some respects subject to reasoning. We may choose a color hue – that is, its character as red or blue, for instance – quite autocratically. However, in regard to color value – that is, its degree of lightness or darkness – and also in regard to color intensity – that is, its vividness – we can be led by considerations other than exclusively by our feeling. As an example: our museum walls will demand light and have a color attitude that is non-aggressive, no matter what the color hue and whether there is over-all color or a play of colors.‘

First column top to bottom:

Davy’s Grey – W&N Watercolour

Turner’s Yellow – Liquitex Soft Body Acrylic

Gris Lichen – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

Primary Yellow – W&N Designers gouache

Davy’s Grey – W&N Watercolour

Turner’s Yellow – Liquitex Soft Body Acrylic

Second column top to bottom:

Velvet Black – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

White

Velvet Black – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

Third column top to bottom:

Primary Yellow – W&N Designers gouache

Gris Lichen – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

Turner’s Yellow – Liquitex Soft Body Acrylic

Davy’s Grey – W&N Watercolour

Primary Yellow – W&N Designers gouache

Gris Lichen – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

Fourth column top to bottom:

White

Velvet Black – Lefranc Bourgeois Designers gouache

White

Fifth column top to bottom:

Spectrum Yellow – W&N Designers gouache

A Colour A Day: Week 26

By Ruth Siddall, on 20 September 2020

A Colour A Day: Week 26. 14th-20th September

Jo Volley writes…

This weeks colours are 7 lake pigments manufactured by Ruth Siddall.

ON THE CHARACTER OF A RED CALLED LAC

CHAPTER XLIII

A colour known as lac is red, and it is an artificial colour. And I have various receipts for it; but I advise you, for the sake of your works, to get the colour ready made for your money. But take care to recognise the good kind, because there are several types of it. Some lake is made from the shearings of cloth and it is very attractive to the eye. Beware of this type, for it always retains some fatness in it, because of the alum, and does not last at all, either with temperas or without temperas, and quickly loses its colour. Take care to avoid this; but get the lac which is made from gum, and it is dry, lean, granular, and looks almost black, and contains a sanguine colour. This kind cannot be other than good and perfect. Take this, and work it upon your slab; grind it with clear water. And it is good on panel; and it is also used on the wall with a tempera; but the air is its undoing. There are those who grind it with urine; but it becomes unpleasant, for it promptly goes bad.

Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte

All pigments are bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper and read from left to right:

Iris green lake – ‘Lily green’

Logwood lake

Logwood ‘chalk’ lake

Cutch #1

Cutch #2

Butterfly Pea Flower lake

Lac lake – Kerria lacca

Mineral Pigment Processing: Health and Safety Tips

By Ruth Siddall, on 16 September 2020

As a geologist, I get asked lots of questions about the safety aspects of preparing mineral pigments and paints, so I thought I’d write down what I have learned during my career as a geologist and answer some of the questions I’m frequently asked. Are mineral and earth pigments safe? Well, the answer is yes and no. Most materials are safe to use if you take the correct precautions on collecting, processing, storing and using them. The more you learn about the materials, the more you understand the risks. The same goes for all artists’ materials, including glues, resins, jesmonite, white spirit and so on. For stuff you buy over the counter, material safety data sheets are readily available. Obviously, this is not the case for stuff you might collect in the great outdoors. Here are some tips, and my personal feelings, about the risks of working with rocks and minerals and how to mitigate them. This applies to people working in sculpture and pottery as well as pigment processing. If you’re grinding rocks and minerals for pigments occasionally and in small amounts, there’s very little risk. However, if this is something you’re doing everyday, you need to take some precautions to protect your health. All dusty materials can affect your respiratory system, but some materials have more damaging effects than others.

What I’m writing here applies to rocks, minerals and biominerals (shells, bone) that you might find in your environment and are regularly used to make pigments or for carving. These tips do not apply to toxic or chemical waste products (which should be avoided at all cost), plants or animal materials (including dyes and lake pigments), or processed products like metals, plastics, resins and glass. Many of you will already know this and take precautions when preparing mineral pigments. However a lot of people are find this activity for the first time. So here we go …

Learn about natural materials and their risks …

Try to learn what you can about what naturally occurring materials are made up of. You can google most things and check their chemical formula. Also look at hazard sheets for similar materials sold by paint manufacturers. Find out what is dangerous and what is not and collect accordingly. Wash your material when you get it home to remove any dirt or potentially hazardous biological material. If you are working with relatively small amounts of these materials every now and again, there is no major hazard associated with them.

It’s all about what you wear …

I’m a lab and field scientist by background and health and safety is drummed into you ALL THE TIME in these environments. There is a reason why you never see scientists in labs wearing, shorts, T-shirts and sandals. In labs, we wear lab coats, face-masks and goggles. We don’t wear this stuff just to protect our clothes or to stop stuff splashing our eyes, we wear it to protect our skin, eyes and internal organs from ingesting dangerous materials. If you’re going to prepare pigments, think like a scientist and dress appropriately. Cover your skin, eyes and mouth. If you are really worried, wear ear-defenders too. As a field geologist we had to wear goggles when we were hammering or crushing rocks. These are proper goggles with a seal round your face (like a snorkel mask but without a breakable glass front) so nothing can get in. A visor won’t stop dust getting into your eyes. This is all really obvious stuff. If you do this, your risk of ingesting or absorbing dangerous substances will be really, really low.

My friend Jim using a rock saw and wearing appropriate safety kit. This is a water saw so there’s no dust, which is why he doesn’t have a mask on. A constant spray of pressurised water washes dust down into the trough. This water has to be disposed of via a sediment trap (and not straight into the drains).

Tidy up and wash-up …

Clean up your work-space thoroughly when you have finished working. Use a vacuum cleaner to get rid of dust. Oh, and have a shower when you’re done! Wash your hair while you’re at it. Don’t eat or prepare food until you’re clean. Really straightforward stuff, but again it hugely reduces risk.

If you are doing this a lot, invest in decent processing kit …

If you are making pigments commercially, and therefore grinding stuff every day, you should probably invest in some proper kit, i.e. mechanical grinders such as disc mills or ball mills AND a proper dust extraction set up.

When I was a grad student, I earned a bit of extra pocket money by rock crushing (as well as crushing tonnes of my research project rocks). You need to crush rocks to a fine powder to study geochemistry and geochronology. I would spend days, weeks doing this. It is quite a slow process. We had a purpose built space with different machines which gradually reduced the grainsize of the rock, starting with a sledgehammer and ending with a disk mill. Also we had a huge set of extractor fans to remove all the dusts. These were like enormous vacuum cleaners which we could move and direct so they were right over the source of the dust and suck it all up. I’ve done a lot of this and I was well aware that the more you do, the more you’re at risk. I still use the lab for grinding if I need to make a lot of pigment. So if you just grind up a handful of ochre once a year, there’s little to worry about (but wear a mask), but if you’re grinding pigments and making paints regularly, you should take precautions and ideally do it in lab conditions where there is protective equipment. Dust is the enemy!

What scares me?

There are a few things that I would not normally grind by hand at home, because they produce specific hazards. Obviously radioactive minerals are a no go. This is not a huge issue with modern pigments but can be an issue when working with some 19th Century materials.

Silicosis is a horrible respiratory disease which comes from long exposure to silica dust. It cannot be cured and it is cumulative; the more silica dust you breathe in, the worse it gets. Silicosis is a killer among workers in granite quarries who have constant exposure, but potters are also at high risk. Breathing in the silica dust scars the lungs and leads to breathing difficulties. Generally, it is best to try and avoid breathing it in. The great majority of rocks on our planets are silicates (sandstones, granites, basalts, schists, slates etc), basically anything that’s not a limestone. I would not advise grinding silicates unless you have proper rock crushing and grinding facilities including extractor fans, as described above. I admit that I have crushed slates and shales by hand, but they’re at the softer end of this spectrum, and I’ve been masked up, etc. But I still regret it. Silicate rocks and minerals includes lapis lazuli and clay-rich rocks. Get it crushed in a proper lab with dust extractors. It scares me when I see people crushing basalt, sandstones, granite etc. Also most silicate minerals lose their colour when finely ground, so it’s a bit of a waste of time. The only silicate mineral worth grinding (in my opinion) is lazurite (the blue mineral in lapis lazuli), but again this should be done in the presence of an extractor fan.

Serpentinites are also silicates but in addition they contain asbestos, so just leave them well alone. Soft, attractive and colourful though these rocks are, I would never grind them, and I don’t even like sampling them at outcrop. The lung cancer caused by asbestos, mesothelioma, is not necessarily dose related. It can be caused by just one, unlucky breath.

A polished slab of serpentinite, a rock predominantly formed of the serpentine group minerals, which can be asbestiform. Serpentinites are very variable in appearance, varying in colour from black, to grey, green, bright red and yellow. They often have a distinctive ‘snake-skin’ like texture and feel soft and soapy to the touch.

What’s an ‘acceptable’ risk?

Some pigment minerals are known to be toxic because they contain heavy metals, copper, cadmium, arsenic, mercury, lead etc. Some of these are super-poisonous, but they are also very important as pigments both art historically and in the present day. As this is what I research, needs must. Heavy metals can build up in the body, so this is dose related – and can do a lot of harm. Some can kill you. You can ingest them through breathing in dust or getting it in your eyes and ears, and some you can absorb through your skin. This risk can be massively reduced by not grinding or working with these materials wearing a vest top! Cover up, mask up, wear goggles. I would never grind large amounts of these minerals. Even though I’m a pretty good mineralogist so I know what I’m looking at, one cannot be sure of precisely what is present in a mineral sample. The unknown unknowns are a problem, microminerals or inclusions of poisonous stuff, or similar looking phases that might be hidden with a mineral. The worst of these minerals are the arsenic and mercury sulphides; orpiment, realgar, pararealgar, conichalcite, cinnabar, metacinnabar etc. and synthetic pigment equivalents like vermillion. Many of the worse pigment poisoners, like Scheele’s Green, Hooker’s Green and some varieties of cobalt violets (i.e. cobalt arsenate) are now banned. These materials are very bad for you, large enough doses can kill. They are also dangerous because they begin to break down thermally and at low temperatures, i.e. not much above room temperature and start releasing straight arsenic. Also, if you have samples of these minerals, don’t have them on an open display shelf, keep them in a sealed bag or box. Keep them away from sunny windowsills! When preparing them as pigments, do so in small amounts, and make sure your skin, mouth and eyes are covered. It’s probably a good idea to wear disposable gloves too. Make sure you was hands and face afterwards, and certainly before eating.

Cadmium pigments and lead pigments are a big risk in the same way, but at least you buy these in powdered form, so there is not the grinding hazard.

Copper minerals, i.e. malachite, azurite, atacamite, chrysocolla, conichalcite (a copper arsenate, so a double whammy, and it looks just like malachite) and lead minerals (to be honest rarely collected as minerals but the main ones are crocoite, galena etc.) are also poisonous, but you would need a much bigger dose to kill you, but they can have lasting damaging effects. Again, the rule is to try to avoid making pigments from these minerals unless you’re in a lab environment, and if you are doing this in your studio, do so in small amounts, cover up and wash afterwards.

The good news is, that once incorporated into a binder, these pigments are much safer, but care needs taking, especially with the very thermally unstable arsenic sulphides.

Something to be aware of is flushing pigments and paints made from these minerals down the sink. Try and avoid doing this!

Above: Conichalcite, a calcium copper arsenate hydrate. Quite a poisonous mineral, as minerals go! This is the nearest natural equivalent to the copper arsenate pigments which were really popular in the late 19th Century.

What’s OK (assuming above precautions are taken)?

Limestones and other carbonate rocks (these don’t contain silica, so no silicosis risk)

Biominerals (shells, coral, cuttlefish bone, bone etc) are carbonates or phosphates and don’t present any major risk, although they can absorb heavy metals during the lifetime of the organism, so this is something to be aware of. Boiling these materials in water before processing, for at least 10 minutes, should kill off any biological hazards and reduce the smelliness!

Iron-ochres and earths – however many of these do also contain clays, which are silicates and they can contain other heavy metal compounds. The purer the iron ochre, the safer it is. You’ve already got a lot of iron in your body, so you need to absorb an awful lot more to make yourself poorly from it. Nevertheless, iron poisoning is a thing. Breathing in a few particles won’t do you much harm, but it’s always best to avoid it. Again, this is more of an issue if you’re processing ochres on an industrial scale but cover up to avoid ingestion of materials and you’ll be OK. However, as dust is the enemy, even if these are not going to poison you, you need to avoid the dust, they can cause respiratory problems.

NB: Not all ochres are iron-rich. Other metals (cobalt, nickel, aluminum) can also form ochreous deposits.

FAQs – I’m happy to add to these!

What about heavy minerals and pollution in the environment?

This is an issue. But again it’s about reducing the chances of your body absorbing this stuff. The are trace amounts of heavy minerals that are pollutants in shells, bones, cuttlefish bone etc., so treat them with care and cover up whilst you are processing them. Clays can hoover up pollution, so take care if you’re collecting clays from industrial or former industrial areas. If you wash them and they smell funny or you get that oily, iridescent film on the water, then to be honest, I would leave it at that and dump them. They can contain some really nasty stuff, like benzene (this is a problem with the London clay in some Victorian industrial areas in London). Brightly coloured mine waste products should be treated with care too. The orange ochre mineral ferrihydrite that you see in streams is usually OK but check what was being mined there as these deposits can also contain arsenic and other horrors. Anything else, personally I’d leave well alone. It is waste for a reason and also sorts of nasty chemicals were used to process it.

Are you saying that I really should be only processing pigments in a lab environment?

No, not at all. Making these things at home is good fun. You just need to follow the basic safety advice; wear a mask and ideally eye mask, wear long sleeves and clean-up yourself and your space afterwards.

I’m still anxious about the risks some of these materials pose and feel I don’t know enough about them. Should I use them?

The simple answer to this question is no. If you don’t feel comfortable using a certain material then just don’t.

I’m getting conflicting advice about the risks of working with a certain rock, mineral or shell. How do I find out what the truth is?

Again, if this is making you uncomfortable, simply don’t use that material. But remember, the hazard is caused by getting this stuff into your body. If you do everything you can to avoid that, then you will reduce the risk. Try to rely on scientific sources rather than social media and hearsay to get more information.

Should I just completely avoid using seriously toxic mineral pigments like orpiment and vermillion?

No, but you should learn about them first and understand what the risks are. There’s lots of safety info out there. These minerals/pigments need handling with care. As I keep saying, you just do everything you can to avoid this stuff getting into your body. I wear gloves for handling orpiment. However, if you have no need to use these pigments they can be easily avoided. You can buy safe modern paints which have similar colours and properties.

Is it safe to teach kids pigment processing techniques?

It’s not safe to use the toxic mineral pigments mentioned above (copper, arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury etc. based pigments), but processing ochres and chalks will be fine and good fun; no more risky than making mud pies. Levigating clays and ochres in water is pretty safe too. Make sure they’re supervised, old enough not to know not to eat it and make sure they’re wearing a mask if they’re working in dusty environments.

Many minerals have therapeutic properties, won’t this help protect me?

No, they don’t and no, it won’t. Sorry. In fact many minerals pose risks as described above and can be very harmful. Breathing in their dust or inserting them into your body can be really dangerous. Also the mineral trade to produce therapy crystals is really, really, really unethical and exploitative a lot of the time … but that’s another story.

Close

Close