Rules-of-thumb ~ are they the answer to our decision making dilemmas at the end of life for people with dementia?

By Nathan Davies, on 5 October 2016

Back in 2011 when I started my PhD and was working on a European study which was examining palliative care services for people with dementia, there was a distinct lack of guidance about how end of life care should be delivered. The only real ‘saving grace’ I guess was the Liverpool Care Pathway. This offered some guidance about what should happen towards the end of life. It was meant to incorporate and describe best practice from hospice care, the ‘gold standard’ of end of life care, and allow it to be translated to other settings such as the acute hospital ward. Although, I say saving grace… really, it wasn’t best suited to people with dementia and it only focussed on the last few days of life.

The Liverpool Care Pathway received some shocking criticism, spearheaded mainly by the Daily Mail and ultimately this led to the removal of the pathway by the UK government in 2013. What we saw in the middle of our projects were practitioners losing more and more confidence in providing end of life care generally, let alone for people with dementia.

This led us to think, what can we do to help with practitioners confidence but not develop yet another pathway or guideline? Maybe what we need is something that is short, easy to remember, prompts us to think and leads us to an action. Cue light bulb moment, and we have the idea of developing rules-of-thumb (heuristics). Rules-of-thumb are simple, easy to remember schematic patterns which help with decision making.

Could we produce something similar to this for practitioners making decisions for people with dementia at the end of life? Well, using a process of continual development and change with families and practitioners, we did. We have produced four rules-of-thumb, covering: eating and swallowing difficulties; agitation and restlessness; reviewing treatment and interventions at the end of life; and providing routine care at the end of life.

The full rules are available on our webpage which you can find here. But to give you a taster our rules consist of flow charts, taking the decision maker, through the thought processes and the individual smaller thoughts and decisions which need to be made about a much larger decision. In the diagram you can see our rule covering agitation and restlessness. The key rule here is to not assume that the dementia is the cause of the agitation/restlessness, but to look for an underlying cause. It also acts as a prompt to the practitioner, getting them to think; what else is going on here? They need to look at the changes that have occurred, thinking not only about the physical causes, but also the environment and the health and wellbeing of the carer. Finally, this rule reassures the practitioner that a cause may not always be found. This is ok!

We tested these rules at 5 different sites; 2 palliative care teams, a community nursing team, a general practice, and a hospital ward. In September we hosted the end of study symposium to

present the final versions and hear some feedback from those on the ground who actually used them.

Gillian Green, a community matron, said they were easy to follow providing common sense advice and she had not seen anything quite like it in her 26 years of experience in nursing.

Caroline Ashton, also fed back on her experiences of using the rules-of-thumb on her complex care hospital ward. She told the audience about how a locum registrar (doctor) on the ward was able to pick up the rules-of-thumb to help guide decisions about a patient, despite having very little experience of end of life care. That registrar has taken the rules away with her to use in her clinical practice.

The feedback we had from sites through our evaluation was great, with suggestions for improvement incorporated into a final toolkit of the rules-of-thumb. We are in the process of analysing the final evaluations and will publish these findings in more detail very soon.

So are rules of thumb the answer? I won’t say yes, but I definitely will not say no! Our experiences is that they have been a good way to get practitioners thinking about some of the basic underpinnings of end of life care, making the implicit knowledge that they have explicit. We have provided many of those involved in the study with copies of the final rules-of-thumb for them to not only continue using in practice but also to share within their wider organisations and colleagues. As I sit writing this blog I have opened another email explaining how the rules-of-thumb we have developed are going to be incorporated into end of life training being developed by the Alzheimer’s Society.

For more information on our work or a hard copy of the heuristics please contact Nathan Davies (Nathan.davies.10@ucl.ac.uk) or alternatively download the rules-of-thumb from our website.

This research was supported by funding from Alzheimer’s Society grant number AS-PG-2013-026 and by the Marie Curie Research Programme, grant C52233/A18873. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not the funders.

Reflections of a Novice researcher

By Nathan Davies, on 20 July 2016

In this post Marie-Laure from the eHealth Unit talks about her experiences of entering the scary world of academia. A very funny post which I am sure many of us can relate to in one way or another.

Visions

I always enjoyed research as an undergraduate and was thirsty for some time to gain in-depth knowledge of one particular field. A two-year part-time academic clinical fellowship (ACF) sounded perfect: I could balance my time between being a GP Registrar and a researcher. The eHealth Unit immediately caught my attention – I had seen what a difference technology could make in a hospital setting and wanted to know all about primary care and public health applications. I was hooked by the dream of developing an app that would save billions of pounds for the NHS, educate people by the millions and save thousands of lives! I let my imagination run away. When I pictured the eHealth Unit at UCL, I saw what I imagine a tech start-up in Silicon Valley to look like: people riding down corridors on segways, ordering their morning coffee from the full-time barista on site, free massage twice a day etc. I stayed up until the early hours completing my ACF application form powered by the thought of the free Coco Pops and Nobel Peace Prizes that would surely come my way. ·

Reservations

Application form submitted: tick. Interview granted: tick. Interview preparation: HELP? Clearly I couldn’t mention the peace prizes and segways in the interview. Yes I enjoyed research as a medical student, but I only had two mediocre publications. Plus, did I really want to be an academic? Would I have to start wearing glasses and spraying Eau de Old Library Book every day? ‘Research’ sounds very nice. But what is it exactly? How were the other ACFs I spoke to so certain of their chosen path in life? Had the Academia Fairy visited them in their sleep?

Enter Professor Murray, who just said: calm down, and be honest. I couldn’t say for sure that I wanted to do a PhD and pursue a career in academic general practice because I didn’t have any real experience of research. And that’s exactly what I told the interview panel. So yes, I was surprised when I was offered the fellowship.

Reality

First day at the eHealth Unit. Free coffee! (Who cares that it’s instant?) My first few weeks were spent familiarising myself with the Unit’s existing work, especially HeLP- Diabetes, the impressive NIHR-funded type 2 diabetes self-management programme, and getting a real sense for what research should look like.

Time to get to grips with my own project. I had exchanged a number of emails with Professor Murray before my start date, and had chosen diabetes prevention as my research topic. I spent at least a month reading and thinking (a true pleasure compared to the pace of seeing patients in general practice). I refined my research questions: what is the evidence that diabetes is preventable? What is the evidence that lifestyle modifications can help to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes in high risk populations? Which components of lifestyle interventions are effective and how do these work? Most importantly: can digital interventions help with these effective components?

With a good grasp of the current literature, I set about planning my research project. The eventual aim might be to develop a complex (digital) intervention so I familiarised myself with the MRC guidance. The first step in any complex intervention is to carry out a thorough ‘Needs and Wants’ assessment, i.e. qualitative work that would be used together with existing frameworks and literature reviews to inform an eventual digital intervention.

It was soon clear that I would need to apply for some funding for this and I put together a rough draft for the SPCR FR11 Grant. This was my first grant proposal. The first time I designed a study protocol. The first time I costed a study and recruited PPI input. The first time I provided the scientific rationale for a study. Does this officially make me a researcher now? I think so. With the help of two brilliant PPI and a very experienced team I put together a grant application. I was over the moon – on a Segway Rocket with a personalized PR0F3SS0R number plate – when I was told it had been successful.

Since the funding was granted I’ve been finding out about ethics and R&D approvals, and exactly why everyone sighs and looks at me pitifully when I say what stage I’m at. Yes, it’s a slow process. But I feel like a real researcher. And I know all the acronyms so feel like I’m part of the gang now. IRAS, HRA, REC, NoCLOR, CRN, PAF, DRN, DSH: no problem.

Reflections

So while free massages and Coco Pops haven’t featured thus far, I can’t say I’m disappointed. I’ve discovered what it’s like to conceive and own a research project and to feel like I have in-depth knowledge of a particular field (no matter how niche digital diabetes prevention may be). I can now say with confidence that I like research. Plus there are many other perks. I’ve attended a number of useful courses and I’ve had to think and learn about marketing strategies, social media and coordinating efforts across the team; skills that are rarely developed at this stage of GP training. And the work environment is incredibly supportive. I feel like I am part of a wider network, with many opportunities.

I also love the mix between clinical work and research. It’s easy to feel frantic and overworked in general practice. The two and half days I spend on my research offer an antidote to this. I’ve found the research has kept me interested in the wider picture too; the background and the many ‘why?s’ that crop up during my consultations. It’s sometimes difficult to balance the two, but none of it is insurmountable.

So, do I want to do a PhD? I can’t say for sure yet. But I wouldn’t be disappointed if the Academia Fairy visited me in my sleep now.

Human-computer interaction

By Nathan Davies, on 12 July 2016

In this post, Nikki Newhouse from the eHealth Unit and UCLIC talks about her visit to the CHI’2016 conference in San Jose, California.

In early May, I visited San Jose in California for CHI’16, the biggest annual conference in the HCI (human-computer interaction) calendar. Held over the course of a week, the conference’s scope is enormous, attracting around 3,000 international delegates who come to learn about and discuss how people interact with technology. Delegates are drawn from a wide range of disciplines and it’s an active, exciting event, where academics and students mix and engage directly with entrepreneurs, designers, industry experts and commercial leaders.

I attended as a participant in the CHI’16 Doctoral Consortium (DC). The DC brings together a small, international group of postgraduate students to explore and develop their research under the guidance of an expert panel. Competition to take part is high: 15 places were allocated from 67 applications and I was honoured to be the only student selected from the UK. The panel consisted of Hilary Hutchinson (Google), Alan Borning (University of Washington) and Yvonne Rogers (UCL). Participation in the DC involves attending a 2-day pre-conference workshop during which all attendees present key aspects of their research and receive constructive feedback from the group and panel on how to take their work forward. There was also the opportunity to develop networking skills and chat informally with invited guests from industry and academia.

Consortium attendees’ presentations represented the huge range of interests, questions and approaches that come under the exciting HCI research umbrella. I presented my multidisciplinary research on the use of technology in the transition to first time parenthood; other students’ work included projects on collaborative writing, working with service dogs, how people interact with digital books, rethinking the role of smart cities from a perspective of supporting wellbeing, and designing digital tools for dispersed populations with rare diseases. As well as gaining valuable presentation practice and personalised feedback, we presented a poster within the main conference and our extended abstracts were published in the highly-regarded CHI Extended Abstracts, available in the ACM Digital Library.

The conference benefits from standout keynote speakers from academia and industry and a multi-track programme that includes talks, workshops, courses, lunches, a job fair, interactive demonstrations, special interest groups and even ‘alt.chi’, a forum for ‘controversial presentations’. I attended an exceptional course on positive computing and designing for wellbeing, facilitated by Prof. Rafael Calvo and Dorian Peters (both University of Sydney) in which we explored approaches to evaluating and designing for wellbeing determinants like autonomy, competence, connectedness, meaning, and compassion. I also attended a hands-on course in participatory design methods, hosted by Aarhus University’s Susanne Bödker, Christian Dindler , Ole Sejer Iversen and Kim Halskov. The course gave an overview of participatory design history, practices and methods. Basically, we had a great time solving design challenges with Lego!

Attending CHI’16 has been one of the standout experiences of my PhD and I feel extremely privileged to be one of the ‘Class of 2016’. HCI is an exciting field to work in: it combines academic rigour and methodological pluralism with fun, curiosity and an inherently pragmatic approach to problem solving. CHI’17 will be held in Denver and I’m already excited about attending!

Patient-Centred Care

By Nathan Davies, on 23 June 2016

In this post Kingshuk Pal talks about patinet-centred care and what does it mean?

Everyone agrees that patient-centred care is a good thing. But what exactly does that mean? And why should we bother?

There are many definitions of patient-centred care. The simplest involves “understanding the patient as a unique human being”. More technical definitions involve lists of interconnecting components like: (1) exploring both the disease and the illness experience; (2) understanding the whole person; (3) finding common ground regarding management; (4) incorporating prevention and health promotion; (5) enhancing the doctor–patient relationship; (6) ‘being realistic’ about personal limitations and issues such as the availability of time and resources.

But true patient-centred care is also professional-centred care. It recognises that health professionals are not automated healthcare dispensers mechanically processing each complaint in robotic monotony. Healthcare professionals are unique human beings too. The doctor is a drug. Healing comes from connections as much as from prescriptions.

We are constantly driven to become more efficient. To do more in less time. But as we get busier and more productive, we give our patients less attention; we give them less of ourselves. We connect with them less.

What can we gain by challenging the paradigms of efficiently delivered, protocol-driven, evidence-based standardised care? What happens when we treat patients as people and give them our attention rather than a prescription?

This is one example based on a true story published in the Lancet last week:

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)30410-X/abstract

A visit to UC Irvine: eHealth research and diabetes education in the United States

By Nathan Davies, on 7 June 2016

In this post Shoba Poduval from the e-Health Unit talks about her exciting visit to California as part of the Ubihealth exchange Programme.

In March, thanks to the UbiHealth Exchange Programme, I visited the Informatics department at University of California in Irvine (UCI) supervised by Gillian Hayes and Yunan Chen. Ubihealth is a global consortium of research institutions with expertise in technology and healthcare, and the exchange programme allows researchers from member institutions to share knowledge and apply it to their own fields of work.

During my visit I met with researchers and clinicians involved in eHealth and patient self-management support. Josh Tannenbaum is an Associate Professor whose research looks at the use of digital games as an educational tool in interactive storytelling and identity transformation, with the purpose of challenging people’s assumptions about others. Professor Tannenbaum suggests that interactive digital games could be developed which allow people to experience life with diabetes, acquire greater empathy, and interact with people with diabetes in a way that is more supportive of positive lifestyle changes.

I met with Terrye Peterson, a nurse and certified diabetes educator at UCI Medical Centre. Terrye delivers diabetes education by visiting patients on the wards to discuss their management and deliver the education. Most people with type 2 diabetes in the US do not receive any structured self-management education, and barriers include limitations to access due to socioeconomic and cultural factors, health insurance shortfalls, or lack of encouragement from healthcare providers to seek diabetes education. In England, referral to diabetes self-management education has become a national Quality and Outcomes Framework (pay for performance) item for GPs, incentivising them to refer patients to a programme. In the US healthcare is funded by government programs like Medicaid, private insurance plans and out-of-pocket payments, and there is no national standardised reward and incentive scheme for referring. Other issues for diabetes management in the US include unaffordable co-payments (top-up payments) for essential treatments and lack of integration between outpatient and hospital care.

I also visited the UCI Centre on Stress & Health which, together with the Children’s Hospital of Orange County, develops interventions to relieve the pain, anxiety and stress of disease and the healthcare environment for children. I met with Drs Michelle Fortier and Zeev Kain to learn more about their work on a web-based tailored intervention for preparation of parents and children for outpatient surgery (WebTIPS).  The programme consists of an interactive website which teaches children what to expect from surgery, and skills for coping with anxiety prior to the surgery. There are games which allow children to place equipment on animated animals and deep breathing exercises to encourage calm. The team have published findings from their randomized controlled trial of the program with children age 2 to 7 years old undergoing outpatient elective surgery. They found that children and their families found the programme helpful, easy to use and it led to a reduction in preoperative anxiety.

The programme consists of an interactive website which teaches children what to expect from surgery, and skills for coping with anxiety prior to the surgery. There are games which allow children to place equipment on animated animals and deep breathing exercises to encourage calm. The team have published findings from their randomized controlled trial of the program with children age 2 to 7 years old undergoing outpatient elective surgery. They found that children and their families found the programme helpful, easy to use and it led to a reduction in preoperative anxiety.

Finally, I met with PhD student Kate Ringland who is studying an online community for children with autism built around the game Minecraft. Minecraft is a creative game which allows players to dig (mine) and build (craft) with 3D blocks whilst exploring a variety of terrains and landscapes. Kate’s research looks at how online communities can help support social interaction for people who find face-to-face communication challenging, such as children with autism. Her results suggest that people with autism are finding new ways to express themselves and connect with others in order to form communities.

Working at the eHealth unit has taught me about the potential for technology to change the way we interact with patients and deliver healthcare. UK eHealth research addresses some similar themes as that of our US colleagues, including patient education and social interaction, but there are also differences in our health systems which mean that interventions need to be implemented in different ways. We can learn from both our similarities and differences, and international exchange and collaboration is vital for sustaining this learning.

Acknowledgements: With thanks to UbiHealth, Nadia Bertzhouse, Elizabeth Murray, Nikki Newhouse, Aisling O’Kane, Louise Gaynor, UCI Informatics, Gillian Hayes, Yunan Chen, Josh Tannenbaum, Terrye Peterson, Michelle Fortier, Zeev Kain and Kate Ringland.

Pharmacovigilance at PRIMENT

By Nathan Davies, on 6 May 2016

What is pharmacovigilance and why is it important?

Pharmacovigilance (PV) is the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse events or any other drug-related problems. It’s an important discipline because it allows us to find out what safety issues relate to a drug with the aim of improving patient care and safety. Without pharmacovigilance we would be giving potentially harmful drugs to patients without monitoring their effects! There is also a specific legal requirement to monitor the safety of drugs in clinical trials.

So what are we doing here at Priment?

Historically, Priment has typically been involved with non-drug clinical trials (psychological interventions, qualitative research etc.) but there has been a desire over the past year or so to expand the research portfolio to include clinical trials of investigational medicinal products (CTIMPs) i.e. drug trials. To be able to achieve this Priment has excitingly developed a PV system and we can now support researchers at all stages throughout a trial with their PV needs. It’s an exciting time for the unit as we are taking on PV responsibilities for two really interesting trials, KIWE and PANDA.

KIWE is a trial that is investigating the use of the ketogenic diet in infants that have epilepsy. They would otherwise have to rely on years of anti-epileptic drug treatment so the findings will be really important for these children and their families. The trial team are based at the Institute of Child Health.

The PANDA trial is comparing the use of an anti-depressant drug (sertraline) with placebo in patients that have depression to find out who might fully benefit from anti-depressants. The team are based at the Institute of Psychiatry and we are also working with them on another trial that will join the Priment portfolio in a few months.

Why?

PV in clinical trials is new to many of the researchers working at/with Priment so we wanted to be able to ensure a consistent approach to this aspect of our work and to be sure that we are working in line with the regulations. By centralising PV we are taking away a barrier to starting work on CTIMP trials and hopefully giving researchers an added benefit of working with Priment as we expand our portfolio.

How Priment supports CTIMPs

We are involved from the protocol development stage right through to trial closure and provide support on protocol development, adverse event management, training, periodic safety reporting and the management of reference safety information (to name a few things!). We are here to support trial teams throughout the clinical trial lifecycle and will endeavour to do our best to provide answers to queries and problem-solve whenever necessary.

What does this mean for Priment?

Priment ‘sits’ within 2 of UCL’s Institutes – the Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care (IEHC) and the recently formed Institute of Clinical Trials and Methodology (ICTM). The inclusion of clinical trials into Priment’s work allows us to contribute to the achievement of the aims of both, notably ‘Evaluating strategies for the prevention & treatment of physical ill health’ (IEHC) and ‘To improve local, national and global health by conducting clinical trials and other well-designed studies’ (ICTM).

What next?

The Priment portfolio of CTIMPs is expanding and we are working on 2 more trials which we hope will be open by late 2016/early 2017. They are RADAR and ANTLER:

The RADAR trial is comparing the use of an anti-psychotic drug reduction programme with maintenance treatment in patients that have schizophrenia and psychosis. By slowly tapering patients off their treatment it is hoped that the unpleasant side-effects of the drugs may be avoided while hopefully keeping patients well.

The ANTLER trial is also investigating a drug reduction programme but this is for patients with depression. An anti-depressant drug reduction programme is being compared to maintenance treatment to find out which types of patients can benefit from reduced drug treatment.

For more information about PV at Priment, or to find out how we may assist you with your trial please contact Charlene Green (PV Coordinator).

One marathon, two marathon, who will do the third..?

By Nathan Davies, on 3 May 2016

An incredible achievement from two members of the department this month. Emma Dunphy and Ann Liljas have both completed a marathon!! Congratulations both! They have given us a short overview of their experiences – any one tempted to run next year..?

Both Myself and Ann Liljas have just completed a marathon. No, not the metaphorical marathons of academic work that PCPH people complete all the time, but an actual marathon. Ann ran Rotterdam Marathon 2 weeks ago and I ran London Marathon last Sunday. Perhaps it’s worth adding that global average (median) for women completing a marathon in 2014 was 4 hours 42 minutes and 33 seconds. Here is a little of our experience.

Ann:

Marathon training requires quite a lot of preparation and having signed up for Rotterdam marathon in April motivated me during the dark and cold winter months to get up early and go for a run before work. Doing several laps around Regent’s Park on my way to work sometimes made me wonder if it was just me running like an idiot at 7am in the dark in order to build up endurance for a long-distance run. On race day those morning runs felt incredibly far away – the sun was shining and I was surrounded by 30,000 other runners in colourful clothes. This was my fourth marathon (of which one was part of an ironman) and my goal was to get a new personal best. Based on my previous experience I know that my greatest strength is that I can keep running at the same pace for a long time. So I started at a pace that felt challenging yet manageable. After three quarters of the run I started feeling lack of energy but managed to keep going albeit slightly slower. But when I saw the finish line in the horizon I thought I better spend any energy left and managed to increase my speed a little. I completed the marathon in 3 hours 33 minutes and 4 seconds – a new personal record by five minutes.

Emma:

I thought I would hate all the training but actually the routine of running to or from work and around the canals, hills, and grotty neighbourhoods of London has been a real pleasure. Well… most of the time. I ran for the Terence Higgins Trust, a charity for sexual health and people living with HIV. It’s a wonderful cause and it was motivating when the race got tough.

On race day, I was absolutely terrified. Even though I had trained well and avoided injury, it was just nerve racking to be facing such a distance, with what felt like the whole world watching. Everything you hear about the crowd lifting you was true, especially with family and friends dotted along the way. Ann was cheering for me at mile 13 but I somehow missed her amongst all the other cheers. I hobbled in at 4 hours 23 minutes, exhausted but very proud. I celebrated with group of friends and some paracetemol. What a day!

Big Bang Data Exhibition at Somerset House

By Nathan Davies, on 8 April 2016

In this blog Tra My Pham talks about a recent visit the Thin team had to the Big Bang Data exhibition at Somerset House.

Our team recently went on a field trip to the new Big Bang Data exhibition at London’s Somerset House. Through the work of artists, designers, journalists and visionaries who used data as raw materials, the exhibition showcased the complex relationship between data and our lives, how data affects the way we do things today and impacts our future.

The introductory section of the exhibition revolved around the concept of ‘the cloud’, a buzzword for online storage services such as Dropbox or Google Drive where we can store and access our data over the Internet instead of using a computer’s hard drive. These conceptually light and intangible services are actually supported by a heavy network of physical servers located in industrial-scale warehouses known as data farms. For example, Facebook’s first data centre in Europe is based in Lulea, Sweden, serving more than 800 million Facebook users. The invisible infrastructures supporting ‘the cloud’, hidden inside such closely-guarded data centres, were unveiled to viewers in Timo Arnall’s fascinating film Internet Machine.

History of data was the main theme of the next section that we went on to see. The last few decades have witnessed an information explosion, which involves a radical shift in the quantity, variety and speed of data being produced, as well as the continuous evolution in the way data can be stored, accessed and analysed. From floppy disks with storage capacity of 1.44 megabytes in the late 80s, we can now easily store and carry around terabytes of data in portable hard drives for everyday use. Going back a couple of decades, storing 1 terabytes of data would require more than 700,000 floppy disks!!!

This section also gently touched on the discipline of data visualisation, which has become essential in capturing and making sense of the abundant data available nowadays. I was particularly drawn to ‘Horizon’ by Thomson and Craighead, a digital collage of real-time images taken in different time zones around the world and constantly being updated, forming what resembled a global electronic sundial.

Some of the work in the next section we visited focused on the issue of data privacy and security, something we all need to consider in our roles in research. For example, by mapping pictures of cats posted on social media in I Know Where Your Cat Lives, Owen Mundy exposed how easy it is to trace the location of cat owners using their own digital footprints.

Other artists’ interest lies in collecting and visualising their own personal data. My two favourite pieces of work in this stream were Dear Data by Stefanie Posavec and Giorgia Lupi, and Annual Reports by Nicholas Felton.

In Dear Data, London-based Posavec and New York-based Lupi got to know each other through postcards filled with data they collected and drew about their weekly activities; from the number of times they looked at the clock to how often they laughed or made complaints.

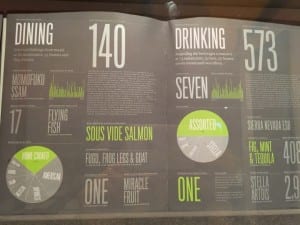

Since 2005, Felton has been gathering a legacy of information about himself, his personality and everyday habits such as dining, drinking, reading and travelling. These data are presented in the form of annual reports, reflecting his activities during the years.

To me, these two pieces brought about a sense of wittiness. However, what struck me most was that there is no single correct way of making sense of the data, and data that seem to be trivial at first sight can be integrated and visualised to tell meaningful stories. As a researcher using a large primary care electronic database, this was by far the most special section of the exhibition to me, and gave me much inspiration for improving the data visualisation aspect of my work.

This section showed how the future form of our data society is being shaped for the common good. What drew my attention was Pixellating the War Caualities in Iraq, a simple yet stunning pixel visualisation created by Kamel Makhloufi to highlight the casualties during the Iraq war. Each pixel had a colour, blue for ‘friendly troops’, green for ‘host nation troops’, orange for ‘Iraqi civilians’ and grey for ‘enemies’. The two images showed the same data but in different presentations. The right image illustrated the deaths as reported chronically, and the left image grouped the deaths by the characteristics of the person killed. This work really emphasised the power of visualisation tools in conveying meaningful messages from large and complex datasets.

We also visited other sections of the exhibition including ‘London Situation Room’, where stories of Londoners were depicted through data, and ‘Black Shoals: Dark Matter’, which was a spectacular visualisation of the world’s stock market.

The exhibition ended with ‘What Data Can’t Tell’. This section featured works to illustrate that using data analysis alone may not be enough to resolve some of our society’s complex issues such as education, health care or war, which also involve a high level of moral arguments.

Before concluding our visit at the exhibition, we made our last stop at The Data Store. This section brought together products that capture data with the aim of enhancing our everyday life, such as personal fitness wristbands, or wearable camera that automatically take pictures over the course of a day, also known as narrative clips.

Flipping their learning, and your teaching

By Nathan Davies, on 21 March 2016

In this Post Melvyn Jones talks about new methods and ways of teaching/learning – something in here for us all to take away to our next class!

In this Post Melvyn Jones talks about new methods and ways of teaching/learning – something in here for us all to take away to our next class!

A room full of students staring at you – “ok teacher, teach us”. We’ve all probably been faced by a passive group of students turning up to be taught and it can be a bit daunting. Mid way through you see the smart phones being glanced at, the odd stifled yawn. How effective is this teaching?

So faced with this should you be doing the “teaching”, or is what you are after for the students to do the learning? What is out there to help you?

I’ve tried out a few of the CALT teaching updates; a lunch hour session where you can get some fresh ideas on making student learning more effective. I went, I sat, but most importantly I took away what I had learnt and had a go.

First up “Flipped learning”- in a world where information is everywhere, is there any point in transferring facts in a lecture anymore? Flipped learning suggests getting the student to use the face to face session with the teacher to try new things out, to understand concepts and to explore any difficulties they are having with the subject matter. The price of this “flip” is that the student must cover the factual material before. It is no longer preparatory reading with all the “optionality” that implies; it is the “meat” of what they will learn. The “lecture” is no longer a lecture but a discussion, an interaction using that material to advance the students’ learning. Your job as the teacher is no longer to passively transfer that information but to help the students understand and interact with it in a way that consolidates their learning. So what if the student hasn’t done the reading? Well that is their problem; the logic goes that if you buckle and go into lecture mode you disadvantage the students that did do the preparation and you reduce the motivation of all the group to prepare for the next session, so hold your nerve. Make sure your students know that this is what you expect and if you teach the same group, be consistent and try to get your other teaching colleagues to do the same.

Next up Pecha Kucha, strictly this is presenting 20 slides on a subject and moving on every 20 seconds, but I tried a “Pecha Kucha lite”, each student talks about a subject using just 1 slide and you set a very strict time limit; I did 5 minute slot per student but adapt it depending on the group size and the time available. Make it fun but also supportive; “bong” them out if they overrun, stop them if they try a second slide or bend the ground rules, but do give them constructive feedback, moderate the feedback from the rest of the group, and make sure everyone is involved. It is a very effective way of getting students engaged, you will very quickly see if they haven’t “got it” or have misunderstood something and most importantly it is the student doing the learning and to a lesser extent you doing the teaching. So what did my students think when I had a go? Their feedback included the following “engaged with learning especially as the result of feedback”. Job done?

Importantly these types of skills (Independent learning, presentation skills, team working), are the skills that our students need to develop, to go out and to get jobs in a very competitive world. The UCL connected curriculum @UCLConnectedC is pushing us to develop research based education, so students learn about research but also that the research informs their learning.

I would strongly recommend these sessions. Whether you do large group teaching, one to one supervision or bedside teaching there will be something for you. You will interact with people from a wide range of disciplines, as varied as Physics to the Built environment, think about your teaching again and probably be back at your desk by 2.30.

Academic Primary Care – Not sinking, nor swimming, but motoring!

By Nathan Davies, on 14 March 2016

This month Rammya Mathew an Academic Clinical Fellow from the Centre for Ageing Population Studies talks about her first and very impressive first time at the SAPC regional Madingley conference which this year we hosted.

This was my first experience of SAPC, and what a fantastic introduction it was. The conference was jam-packed with inspirational speakers, some of whom have paved the way for academic primary care, and many more who look set to be future leaders within the field. The question posed to us by the chair, Professor Elizabeth Murray, was ‘Innovatio n in a sea of change – will academic primary care sink or swim?’. However, the overwhelming attendance and the enthusiasm among delegates spoke volumes in itself, and provided a sound evidence base for the conclusion, which I will share later.

n in a sea of change – will academic primary care sink or swim?’. However, the overwhelming attendance and the enthusiasm among delegates spoke volumes in itself, and provided a sound evidence base for the conclusion, which I will share later.

The opening keynote speech by Professor Martin Marshall challenged our views of traditional research. The need to bridge the gap between the knowledge base that academia provides, and what actually happens in clinical practice was brought to our attention. He introduced the concept of participatory research, and by sharing his own experiences of being an embedded researcher in East London, he demonstrated the impact that this model may have in terms of knowledge creation and mobilisation.

The ‘Dragon’s Den’ was an exciting new addition this year. For some reason, our esteemed judges got slightly confused and enacted the ‘Strictly come dancing’ panel instead. But we had to forgive their mishap, as their sense of humour more than compensated for the error. The calibre of the candidates that were pitching was truly remarkable. Dr Kingshuk Pal from UCL propositioned HELP DIABETES – a fully-fledged online website that supports self management of diabetes.  However, the dragons were fierce in expressing their concern that HELP DIABETES would be another tool best suited to those who are already self motivated. The second pitch was by the medical education department at Imperial College London, who were asking for all medi

However, the dragons were fierce in expressing their concern that HELP DIABETES would be another tool best suited to those who are already self motivated. The second pitch was by the medical education department at Imperial College London, who were asking for all medi

cal students to go to jail!  They put forward a passionate argument that this would improve their understanding of health inequalities and provide experiential learning of working with marginalised groups. This was a moving presentation that tugged at the heart strings of the audience, but the dragons questioned what would be removed from the curriculum in order to make way for this initiative. The last and final pitch was an online pathway, which offered advice, testing and treatment for chlamydia. Being practical and having demonstrated proof of success, it sealed the deal.

They put forward a passionate argument that this would improve their understanding of health inequalities and provide experiential learning of working with marginalised groups. This was a moving presentation that tugged at the heart strings of the audience, but the dragons questioned what would be removed from the curriculum in order to make way for this initiative. The last and final pitch was an online pathway, which offered advice, testing and treatment for chlamydia. Being practical and having demonstrated proof of success, it sealed the deal.

One of the things that stood out to me from the presentations at SAPC this year, was that the conference clearly demonstrated the excellent insights that well-conducted qualitative research can offer. A particular presentation which highlighted this was by, Dr Nadia LLanwarne from Cambridge. She presented the findings of her research, exploring the missed opportunities for diagnosing melanoma in primary care and the patient experience along this journey from initial presentation to diagnosis. I certainly came away from the conference this year, feeling assured that qualitative research is both valuable and necessary – its role was cemented, in terms of putting quantitative research into context and relating it to the real and often ‘messy’ world we face in general practice.

Professor Roger Jones, editor of the BJGP, rounded up the conference with an excellent plenary session. Using his personal story, he talked about the degree of change we have seen in primary care over the years – across academia, education and clinical practice. It was a real eye-opener! It was encouraging to hear the he still looks forward to going to work everyday and has maintained his enthusiasm for general practice, despite the ever changing working environment. Finally, the conference came to a close and we unanimously concluded that academic primary care was not sinking, nor swimming, but was indeed motoring!

Close

Close