In this blog, Dr. Rozhen Mohammed-Amin, Co-Director of the Nahrein Network, discusses the Cultural Heritage Organisation’s (CHO) new initiative: the Digital Heritage Internship Program (DHIP).

Follow CHO on X: @Cho_Kurdish

In 2016, my post-PhD academic plans hit the walls of a (largely) disconnected higher education system in Iraq and its Kurdistan Region. Bringing students from different disciplines and departments to think together and deliver interdisciplinary digital heritage projects proved much more difficult than I had anticipated and prepared for. The stubborn silo and teaching-intense higher education system also brought teaching overload for students and faculty members’ competition for those teaching hours. Add to these a debilitating economic crisis in the Kurdistan Region that resulted in an up to 75% reduction in the salaries and (therefore) reduced working hours of public servants, including academics in public universities. These and other factors left the departments with no time, space, and (for most) motivation to explore new teaching and learning approaches for their students. Outside of curriculums, the local higher education landscape, environment, and culture were/are not very receptive to new non-traditional approaches either. After all, in practice, interdisciplinary research papers involving academics from different disciplines are not approved for academic promotion purposes. So, justifying interdisciplinary projects for undergraduate credits in different departments within such a silo system was/is a very difficult task.

My Nahrein Network Co-Investigator fund empowered me and my team to try transformative teaching and interdisciplinary learning approaches through our new Digital Heritage Internship Program (DHIP). The program brings together and trains local youth (mainly graduates) from different disciplines to conceptualize, design, develop, promote, and fundraise for innovative digital heritage projects. They do so using state-of-the-art technologies like Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR). DHIP aims to connect heritage protection and promotion with local and global needs and challenges for the sustainable development of the Kurdistan Region and Iraq’s heritage. The program also equips local youth with 21st-century digital knowledge, skills, and networks for expanding the creative industry in the Kurdistan Region and the rest of Iraq for making cultural, social, environmental, or economic impacts. Through this program, we strive to practically embody “think globally, act locally” in our digital heritage Research and Developments.

In its first pilot year (2023-2024), we brought together and trained 15 graduates (10 women and 5 men) in Sulaimani city from a total of 12 disciplines within Engineering, Design, Social Science, Arts, and Humanities, and IT. Having more women in the program was one of our objectives for addressing the vast digital literacy gap between men and women in Iraq[1]. In the first six months of the program, we delivered a total of 120 hours of structured training sessions (in-person or online), accompanied by work sessions as well as in-person and remote consultations in team or individually. We also integrated peer learning in some parts of the program. The gained knowledge and skills were applied in the team capstone projects, assigned by our team from the Cultural Heritage Organization (CHO) and the Kurdistan Institution for Strategic Studies and Scientific Research (KISSR).

[1] https://iraqtech.io/digital-illiteracy-isolating-iraqi-women-from-the-outside-world/

Our CHO-KISSR team and international and local collaborators provided extensive in-person and online training in DHIP. Learning from esteemed and supportive international and non-Kurdish speaking trainers like Mary Matheson (Arizona State University), Dr. Akrivi Katifori (Athena Research Center), and David V. Madrid (Historic Environment Scotland) was truly rewarding for our interns and for building their confidence at an international level. To encourage role modeling, we targeted more women trainers. The interns received theoretical and hands-on training in a wide range of topics they take to imagine and develop for the interdisciplinary and multi-dimensional world of AR and VR-based heritage experiences. The training ranged from independent learning to AR and VR experience assessment and everything in between, Design thinking, AR and VR experience design for heritage, historical research methods, immersive storytelling, story writing, storyboard development, team building and working, photography, photogrammetry, drone use, 360 tours, UX/UI design, crowdsourcing in heritage, participatory design, design for participation, AR and VR development in Unity Game Engine, communication, community engagement, marketing, proposal writing, and fundraising.

Capstone Projects

By design, DHIP training and learning is project-based. Such training is intended to not only enhance and consolidate the program’s learning outcomes but also to build the interns’ portfolio in the utilization of promising AR and VR technologies in the field of heritage and beyond. Our CHO-KISSR team has foreseen the local need for investing in AR and VR knowledge and skills even before the recent labor market survey, led by KRG’s Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research and its partner universities, IREX, and the US Embassy/Baghdad. We identified the main themes of the assigned capstone projects based on a local need or requests of local stakeholders, who were excited or inspired by our past Talk to Sarai[1], Virtual Sarai, and Feel Like Me digital heritage projects. We also connected the project themes to global and local challenges and needs such as climate change and women empowerment.

In a span of 10 months and with the four-team capstones, the interns managed to greatly impress those who supervised, heard about, or experienced their projects! The depth and breadth of their activated imagination in the digital heritage field, creative thinking, and synthesizing have shocked our team, collaborators, and even international trainers like Mary Matheson.

[1] https://www.ucl.ac.uk/nahrein/news/2021/nov/talk-sarai-telling-stories-digitally

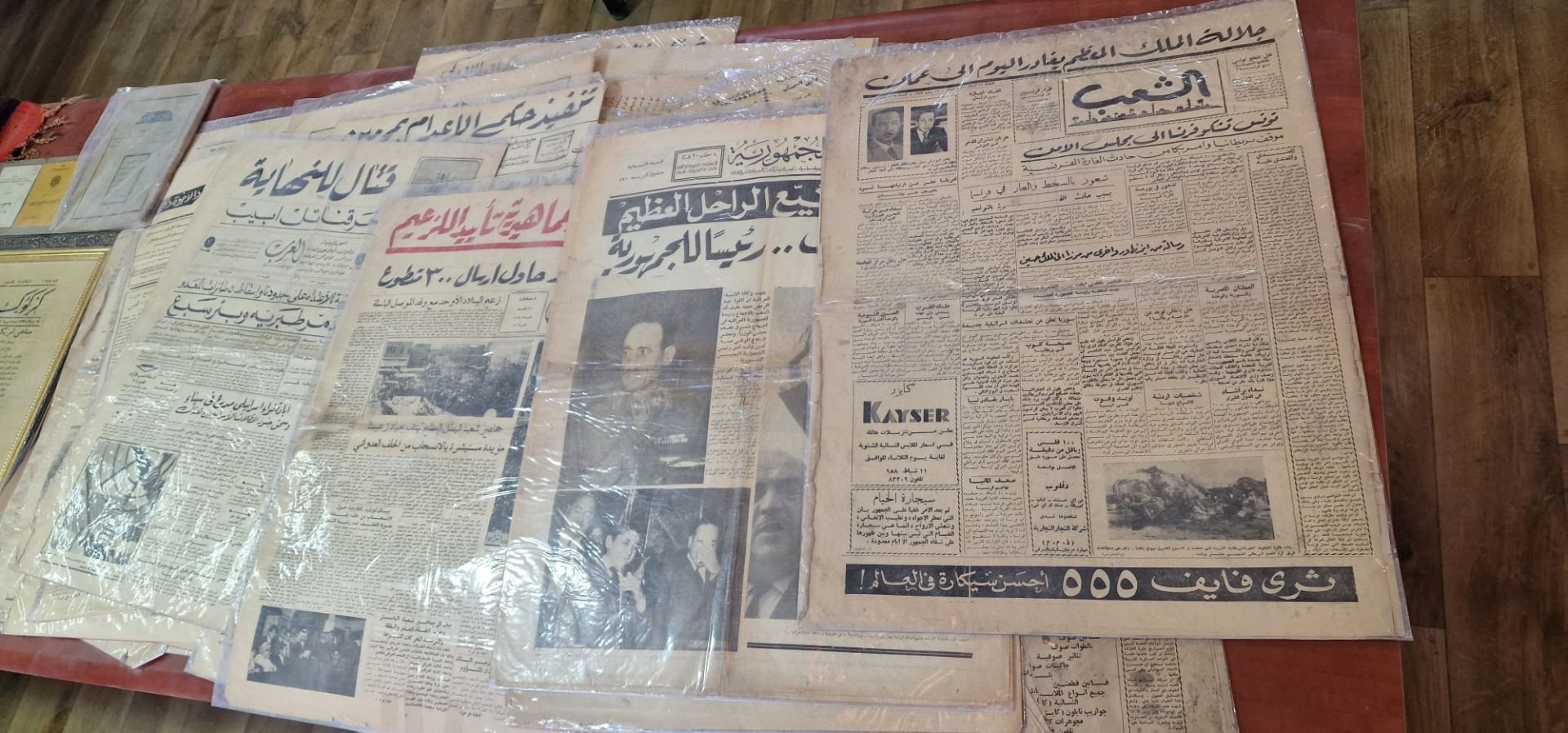

The Historical Empathy

Learning from Our Past Thinker VR Project guides users through the life, stories, memories, writings, and wisdom of Piramerd, a celebrated local poet, writer, and founder of the influential Zheen printing house and newspaper. Through a blend of visual and aural immersion, the VR experience aims to evoke empathy in users by allowing them to connect with the poet’s lived experiences and legacies, focusing on his dedication to education, ethical journalism, cultural advocacy, and public service.The project fosters an appreciation for heritage and historical understanding that can bridge the knowledge and emotional gap between past and present generations.

The Climate Heritage

Bridging Art, Culture, and Heritage for Protecting Environment VR Project combines the power of heritage, technology, and storytelling to immerse users in the sights and stories of the escalating pollution and environmental crisis of the Tanjaro River, near Sulaimani City in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. By immersing users in the perspectives of a local fisherman, an eagle, and a fish, the experience shows and tells about the massive pollution occurring in Tanjaro. The project aims to raise users’ awareness about the largely overlooked but fatal environmental crisis around them and to inspire sustainable actions.

The Historical Evolution of Cities

How Industrial Change is Changing our Life AR Project showcases the economic, social, and cultural influences of Sulaimani City’s first factory, the former Cigarette Factory (renamed as the Culture Factory). By integrating location-based storytelling with witness testimonies, the interactive tour engages users with the factory’s transformative impact on the city and its people. It also unveils unheard-of or little-heard stories and encourages reflections on how industrial rise and fall can create and transform a vibrant economic and social centre into an abandoned ghost complex, and how such neglected spaces can be repurposed into a creative hub.

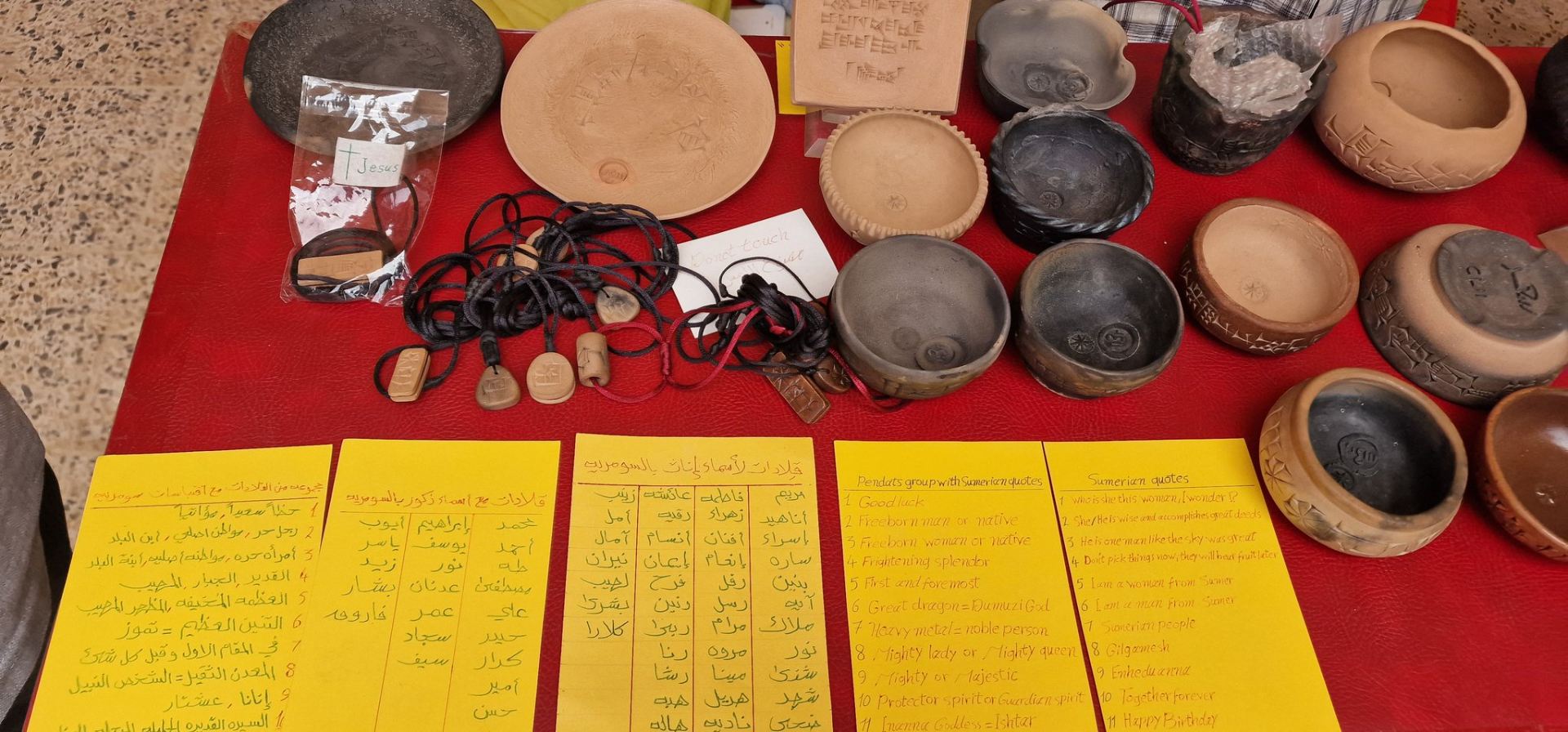

The Narrative Spaces

When Storytelling Meets Design, the AR Project enriches the physical spaces of Hotel Farah (renamed to Kurd’s Heritage Museum), the oldest hotel in Sulaimani City and a current museum, by adding narrations through a statue and displayed collections. Through a mix of captivating stories from historical figures and fictional characters, the mobile AR tour unfolds the stories and significance of the building, related people, and its current collections. This interactive journey through time and space heightens users’ engagement with the museum space, drawing their attention to its diverse components, contents, and stories. The project aims to enrich visitors’ experiences with and perceptions of heritage places.

In designing and developing each of these capstone projects, the interns worked closely with diverse experts and local stakeholders. This close engagement and co-creation exposed the interns to real-world challenges and problem-solving related to (among others) finding scarce archival resources, handling diverse (and sometimes competing) interests and requests, and balancing ambitions with resource and technical capabilities. The project-based nature of DHIP proved to be the “glue” for holding the interns together and to the programme as they were navigating the many challenges of the underdeveloped infrastructure of AR and VR developments in the Kurdistan Region and the rest of Iraq. Our planned post-DHIP promotion of the projects through the local stakeholders and interns themselves promises to further deepen the interns’ interest, and sense of ownership for the promotion and expansion of the projects, and local heritage.

Beyond Expectations

As we embark on the formal and in-depth evaluation of our pilot internship, some interactions and outputs are worth celebrating. First, the high retention and attendance rate of the interns in the program came as a surprise, even to our best-case scenario and most positive team member! Warned by the experience of other training and internship programs and refusing to adopt the penalty measures some of these programs had to take to protect against high dropouts (even in the case of paid internships), we expected to retain only one team of four in our non-paid internship by the end of the originally estimated four months of our program’s life span. Yet, even after extending the structured training for another two months and the whole program for a total of 10 months for completing and testing the scaled-up capstones, we retained all the interns. Only two interns were absent slightly below our high threshold of 90% of attendance. Some of the interns had zero or close to zero absences.

Beyond numbers, the scaling up of the capstone projects by the interns and the enthusiasm the four teams showed for their projects speak volumes about the overall high engagement of the interns with the program and increased interest in digital heritage. This happened despite the fact that the majority of them had not heard about AR or VR before the internship and only a few of them initially showed interest in heritage.

The co-creation nature of our interns’ digital heritage projects proved (at least from our perspective) highly effective for engaging these young interns with heritage promotion and protection and raising their heritage awareness to a degree that even we, the organizers, did not imagine when we planned the program. The content and stories they found and the connections and reflections they made were truly impressive and inspiring. It is also fair to say that the interns helped to achieve one of the main overarching goals of DHIP, establishing a digital heritage network. Although we have yet to publicize the projects in a closing ceremony, we have been approached by excited local community members and media to try and feature our interns’ projects.

A Demanding Ride

Running the program was anything but smooth. Disruptive thinking and working is never easy anywhere, let alone in Iraq. We experienced and had to solve/balance many logistical and technical challenges. One of the challenges has been the scattered state of local heritage collections, resources, and even knowledge. Balancing the needs and competing interests of stakeholders was another challenge. As it turned out, flying a permitted drone (needed by one of the groups for 360 tours) in a post-conflict country like Iraq is far more complicated and team and paperwork-consuming than what we had prepared for.

Managing our interns’ growing expectations was another key challenge to solve. As an ambitious educator and an immensely curious scholar in digital heritage, I was finding it really hard to limit the interns’ growing ambitions in the face of time, resource, and expertise limitations. Then there were challenges related to team dynamics and equitable contribution among the interns.

Also, from the early stage of applying, we experienced an imbalance in recruiting interns based on the four targeted main disciplines and subdisciplines. We could not find or attract any intern with basic skills in the technical development of AR and VR. Although our interns’ feedback and incoming requests point to our limited promotion of DHIP and passive recruitment strategy, limited local skills in computer programming, software development, and/or Game Engine use are reported/observed by many others. In fact, our own team’s software developer had to self-taught himself about AR and VR development due to a lack of such training in and outside his university program. Add to these, the very limited infrastructure and external local expertise in the technically demanding and fast-growing world of AR and VR developments. As a result, the recruitment imbalance extended to the teamwork and the workload of our CHO-KISSR developer. Although the technical development (understandably) was not picked up by almost all of these non-technical interns, the program created a good pathway for increasing the motivation of our existing interns and others. We managed to increase local appreciation and understanding of what it takes to (for example) open a virtual book from the right (not left) side and why local culture, language, and perspective matter in creating or blending virtual and physical worlds.

Internally, our CHO-KISSR team also experienced an imbalance when two key team members started their postgraduate studies in the early months of the internship. So, other team members periodically stepped in to cover for them to ensure the quality and depth of DHIP. Periodic covering for each other and work catch-up is a supportive team culture that we are proud of because it has been making our largely women team accommodating and accessible to mothers, students, and others with proven long-term commitment and dedication but periodically require flexibility.

I should also mention that since the start of the first lecture of the program and referrals, we have been receiving calls, emails, messages, and even visits from local students and graduates inquiring about the start date of a new round of DHIP and expressing interesting in registering in our program.

The “Shoulders of the Giants”

The planning and implementation of DHIP stood on the shoulders and insights of several giants that I would like to acknowledge. The root of DHIP and its inspirations dates back to my life-changing postgraduate studies at the University of Calgary in Canada and my transformative experience as an intern at the Human Interface Technology Lab of New Zealand or HITLabNZ (based at the University of Canterbury). At the University of Calgary, Prof. Richard Levy, Prof. Tang Lee, Dr. Jeffrey Boyd (my supervisors), Prof. Branko Kolarevic, and Prof. Sebastian von Mammen have inspired and guided me in connecting heritage with digital technology. These have been two areas of my intellectual curiosity and activating imagination since my childhood, and all the way to my postgraduate education and ongoing scholarly pursuits. My postgraduate exposure and interest was further consolidated by my experience at HITLabNZ. The inspiring nature, culture, and environment of this leading AR and VR research lab profoundly increased my appreciation for positive and supportive research and education environments and networks. HITLabNZ and its then-director Prof. Mark Billinghurst have deeply embodied the lab’s people-centered approach to finding technology-based solutions and inventions. The very idea and conception of DHIP was inspired by the “Virtual Intern Program” from Mark’s current Empathic Computing Laboratory (based at the University of South Australia) and informed by local and international consultations and need assessment. My transformative postdoctoral experience, funded by the Nahrein Network and BISI and supervised by Prof. Maria Economou at the University of Glasgow, was pivotal in shaping our interns’ emotionally engaging and empathy-driven storytelling approach for designing and evaluating their AR and VR projects. Beyond contributing knowledge and methodological guidance, Maria played a crucial role in connecting me with the highly inspiring and insightful EMOTIVE project and team members such as Dr. Akrivi Katifori (Athena Research Center), who delivered training to our interns. Another significant outcome of my visiting scholarship was meeting Dr. Lyn Wilson and establishing connections with Historic Environment Scotland (HES), whose direct support was instrumental to DHIP’s success. The consultation of Gabo Arora from Johns Hopkins University and his colleagues from LightShed (Barry Pousman and David Samuels) helped with setting up the pillars of the program. The critical insights of Prof. Eleanor Robson (Nahrein Network’s director) and the support and informed feedback of Abdullah Bashir (a Senior Business Advisor and a former member of 51 Labs) and some of his colleagues provided timely guidance for minimizing the program’s blind spots. In the logistical planning of the program, we also received feedback and support from Mustafa K. Ali and Ravin Rizgar (from Suli Innovation House), and Dr. Khabat Marouf and Dr. Vian M. Faraj (from Culture Factory). During the implementation, the program also received generous support from Dr. Lyn Wilson and her colleagues at the Historic Environment Scotland and many supportive local collaborators from organizations such as Zheen Center, Waterkeepers Iraq, KISSR, Kurd’s Heritage Museum (Hotel Farah), Culture Factory, Slemani Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage, Jamal Nabaz Museum, Anwar Sheikha Medical City, and beyond.

The Unknown Soldiers

I cannot write about DHIP without expressing my deep appreciation and gratitude for the dedicated CHO-KISSR team members who worked on running the program, with Khelan S. Rashid and Khazan F. Salih at the forefront, followed by Karo K. Rasool, Tabin L. Raouf, Khanda S. Majeed, Alan K. Sharif, Shajwan H. Abdalla, Davin D. Ahmed, and Bestun O. Amin. In addition to the giants, the demanding implementation of this program would not have been possible without the extra mile and immense care of these unknown soldiers. I would also like to thank the other CHO-KISSR team members (Roza A. Radha and Gulala A. Aziz) and our volunteer (Niyan H. Ibrahim) who indirectly and through their work for the CHO-KISSR team contributed to the program.

Close

Close