Dr. Ali Naji Attiyah, University of Kufa, Iraq

I was hosted by Dr. Edward Denison from UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture, from 10 February to 23 April 2020, on a BISI-Nahrein Network Visiting Scholarship. My main goal was to write an article on the importance of linking both types of heritage, tangible and intangible, in increasing people’s awareness of the role of heritage in their lives.

Seminar at UCL

Eleanor Robson, Sadiq Khalil and Ali Naji at UCL IAS on 13 February 2020

The Embassy of Iraq and Nahrein Network-University College London organized a symposium on the sustainable development of cultural heritage and archaeology on 13 February 2020, chaired by Professor Eleanor Robson. First, Dr. Sadiq Khalil presented a paper on heritage management in Iraq. Then I gave a paper on the role of cultural heritage in Najaf.

The attendees were professors with different disciplines such as history, archeology, architecture, and environment, in addition to other attendees who were interested in Iraq’s heritage.

The seminar was in the first week of the scholarship and it was a good opportunity to meet other specialists in heritage with different disciplines. Moreover, in the discussion after the seminar, the attendees responded very positively to my paper, finding that relating both types of heritage, tangible and intangible, is an attractive strategy to get a more holistic view of the importance of heritage.

Ph.D. Research Projects 2020 Conference at Bartlett School of Architecture

The exhibition space of the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

My host institute was the Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL and the host professor was Dr. Edward Denison, who has an interest in heritage. On 18 February 2020, the Bartlett ran an interdisciplinary conference and exhibition, featuring the work of students from across the faculty who are developing or concluding their doctoral research.

The conference and the exhibition aim to encourage discussions between students, staff, invited guests and critics, and the public. I attended the conference and exhibition to listen to the research ideas in architecture and those trends related to cultural heritage.

One presentation was particularly relevant to my work, by Amr El-Husseiny, whose PhD title is: “The Boundaries of Heritage: A Socio-Political Approach to Heritage Spaces in the Egyptian Context”.

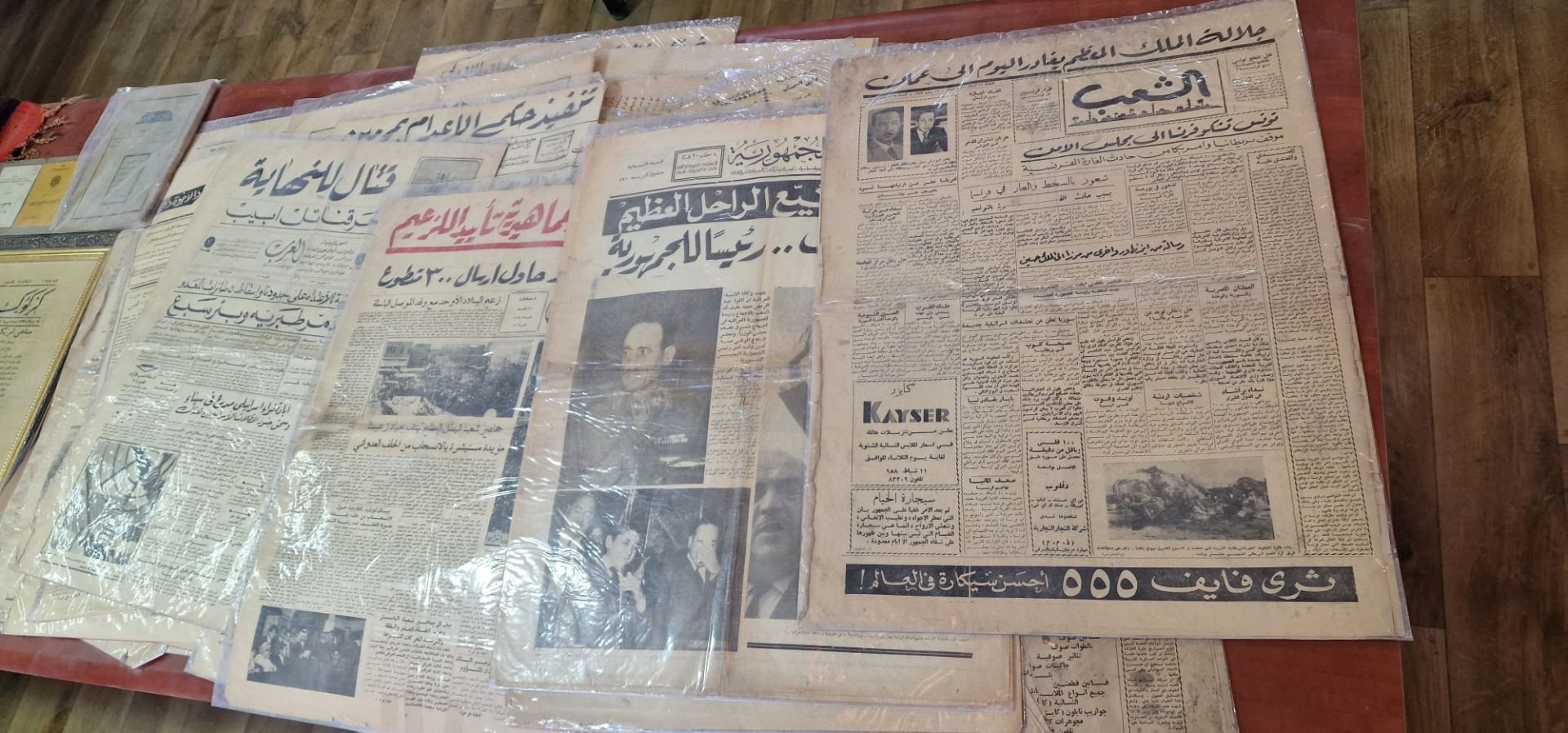

Heritage Workshop at Barcelona

The participants of the conference on heritage for peace, Barcelona, 5 March 2020

A workshop was organized by Heritage for Peace, together with the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas (ALIPH) and Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), 4–5 March 2020. The workshop was on the empowerment of civil society for the protection of cultural heritage in conflict areas and was held in Barcelona, Spain.

The event was attended by many representatives of civil society NGOs from Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, as well as members of State Boards of Antiquities, who had the opportunity to present their work and discuss their needs, as well as experts from the University of Oxford, Blue Shield, Syrian Heritage Archive Project, University College London, and others. I gave a presentation titled “Holistic View of Cultural Heritage in Historic Centre of Najaf City”, in which I tried to describe the role of local communities represented by NGOs in the protection of cultural heritage.

The event concluded with the launch of the Arab Network of Civil Society to Safeguard Cultural Heritage, ANSCH. I am delighted to be one of the founders of this network, which has the following objectives:

- To create a network of civil society organizations.

- To identify and define the heritage protection projects needed in Arab countries.

- To enhance the visibility of civil society organizations and their work.

- To empower local communities’ participation in the management of cultural heritage.

- To foster inclusive social development.

- To foster inclusive economic development.

- To promote the protection of the environment.

The website https://ansch.heritageforpeace.org/ will be a platform to exchange ideas between peers from countries that have a similar unsettled situation.

Meeting with ICOMOS-UK

On 12 March 2020 I held a Skype meeting with Clara Arokiasamy, the Chair of the ICOMOS-UK’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Committee, which she founded in 2012. The main points discussed were establishing ICOMOS-Iraq and the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage.

Webinar at the University of Oxford

On 17 March 2020 I gave a webinar for the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA) project, based at the Universities of Oxford, Leicester, and Durham. I described the role of intangible cultural heritage in the revival of tangible heritage, using historic City of Najaf as a case study. The discussion with experts following the webinar was very fruitful.

Research visits

Dr Ali Naji in Letchworth Garden City, March 2020

On 21 March 2020, I visited Letchworth, the world’s first Garden City, with Yasmin Shariff, the Director of Dennis Sharp Architects. Letchworth was created as a solution to the squalor and poverty of urban life in Britain in the late 19th century. The garden city movement is a method of urban planning in which self-contained communities are surrounded by “green belts”, containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. It shows how the life of local communities can be modernized while keeping their cultures and traditional way of life.

To increase my knowledge of tangible heritage and how it can be used to improve the lives of people, I visited three cities: London, Cambridge, and Liverpool. Apart from London’s four world heritage sites, there are many places inside Zone 1 that maintain their cultural characteristics such as buildings facades and streets. The same thing can be seen in Cambridge, where the buildings and streets are the same for hundreds of years, while six areas in the historic centre and docklands of the maritime mercantile city of Liverpool bear witness to the development of one of the world’s major trading centres in the 18th and 19th centuries.

I learned that in order to keep the cultural heritage in any city, which is still full of human activities, it is necessary to give priority to infrastructure. For example, London, a city of about 18 million people, needs an effective public transport system for daily travel to take pressure off car use. The University of Cambridge is a good example of the use of heritage buildings in new functions, encouraging people and authorities to be aware of the conservation of those monuments. The world heritage site in Liverpool represented by the docks was used for tourism and it was the identity of the city at the same time. Recently, its heritage value was threatened because of the new development project (Liverpool Waters) in the harbour. This is a good example of the sensitivity of the over-commercial use of heritage sites.

While in London I also visited the British Museum, the Science Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Sir John Soane’s Museum, as well as the History Museum of Catalonia when in Barcelona. While all very different in their aims, they share the idea of inter-generational communication of heritage.

Chapter in Handbook of Sustainable Heritage

As an outcome of this Visiting Scholarship, with UCL archaeologist Dr. Caroline Sandes I will co-author a chapter of the new Handbook on Sustainable Heritage, to be published by Routledge and CRC Press. Titled “Najaf, Iraq: developing a sustainable approach to threatened heritage”, it will examine the problem of threatened heritage in Najaf and how a more holistic approach, particularly involving the city’s intangible cultural heritage, will help to work towards a more sustainable conservation program that will encourage and involve local inhabitants to protect Najaf’s important heritage.

Dr Ali Naji in Liverpool, March 2020

Close

Close