The low groundwater level in Babylon

By Zainab, on 20 February 2024

BY AMMAR AL-TAEE

Babylon, especially as the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 BC), is significant for its historical and cultural accomplishments but it also was a place where early technologies sought to address water management through incomparable feats of engineering. The Shatt al-Hillah, one of the branches of the Euphrates River, passes through the center of Babylon, dividing it into eastern and western parts. That relationship served well in trade, transport, defending the city, and irrigating its fields, but it also posed complicated challenges to maintain the city. Groundwater, tied to the level of the Shatt al-Hillah, continued to confound the Babylonians throughout the city’s history. Likewise, it posed challenges to modern archaeological excavations. First, the German presence at the turn of the last century, and later Iraqi expeditions, struggled to go deeper into the city’s archaeological layers; as soon as they were excavated, pits filled with water, preventing archaeologists from knowing more about the early periods, including those of Hammurabi.

Water shortages in the Shatt al-Hillah occurred in the second half of the 19th Century because the intensity of discharge of the Euphrates caused scouring of the river bed downstream of the Shatt al-Hillah branch. Hence, water movement increased toward the main branch of the Euphrates with fewer discharges into the Shatt al-Hillah; sediments began to accumulate in the Shatt al-Hillah branch causing the river bed to rise. Ottoman Authorities took measures in the last quarter of the 19th Century when a French engineer named Schoenderfer was entrusted to find a solution. A weir across the Euphrates River was built, but it could not withstand the currents.

After the British engineer Willcock’s intervention, a barrage known as the Hindiyah Dam was completed and opened in 1913, and as Shatt al-Hillah water levels began to rise again, so did groundwater levels in Babylon. Between the initial weir and barrage, there was a golden opportunity for the Robert Koldewey expedition to excavate Babylon. Olof Pedersen mentions in his book Babylon the Great City that in between the constructions, the groundwater dropped to −3.55 meters (= 21.95 MASL, meters above sea level), allowing Koldewey’s team to excavate down to levels now impossible to reach. As a result, the first excavations of Old Babylonian and Middle Babylonian levels took place at higher parts of the city, especially at private houses in the Merkes area.

Figure 1, North wall of the Palace after the groundwater level decreased, November 1911, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft

After the barrage was built at Sadat al-Hindiyya, the groundwater levels at Babylon became one of the biggest problems facing the process of developing the ancient city for tourism. In the late years of royal rule, the Iraqi monarchy sent experts, headed by young archaeologists Taha Baqir and Fouad Safar, to ascertain ways to develop Babylon’s visitor infrastructure and find appropriate solutions to the issues of groundwater levels. The responsible team set to work, but alas, the monarchy soon collapsed in 1958 with a military coup led by Abdul Karim Qasim and the project was halted.

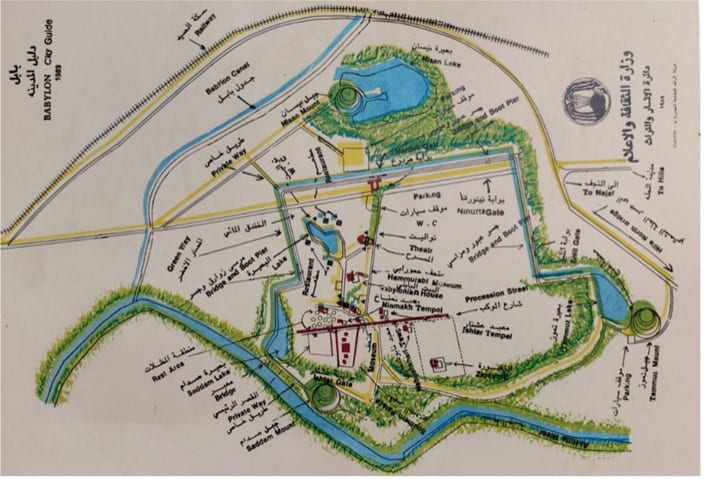

Later, referring to the King’s initial idea, Saddam Hussein launched a project called the ‘Revival of Babylon’ and instructed Iraqi archaeologists and engineering teams to start planning tourism development. The first initiative, coming out of a 1979 international conference, addressed the issue of groundwater under Babylon. However, the revival of the country’s heritage and archaeological resources was hijacked by Hussein’s political ambitions steeped in a personal agenda, which cost Babylon an important and essential part of its heritage.

With the beginnings of the Iraq-Iran war in full swing and accompanying signs of political unrest in the country, Saddam Hussein sought to enhance his personal glory by twisting the Babylon project, and instead of working to address the high levels of groundwater, he dug water canals with four artificial lakes, surrounding the central part of Babylon with water on all sides, and the groundwater problem increased. Between the 1960s and 1980s, the effect was caustic on Babylon’s exposed archaeology. The increased moisture brought salts with it, and capillary action devastated the original masonry walls just above ground level; Ishtar Gate’s famed animals, the mušhuššu-dragons and the bulls, began dissolving into dust.

Figure 2, Map of Babylon after completing Babylon Revival Project and filling the lakes with water, 1989, credit: SBAH

Several cosmetic remedies tried to hide the problem by treating Ishtar Gate’s degrading masonry symptoms rather than solving the root cause. Rather than replace crumbling ancient Babylon’s mud and bitumen mortars and respect Neo-Babylonian brick types, the Ishtar Gate was subjected to heavy-handed and inappropriate cement mortars and wrongly selected brick masonry infills. Instead of matching the Neo-Babylonian masonry, a patchwork installation featuring modern construction bricks normally used in houses was installed. To add insult to injury, at the Ishtar Gate, a heavy concrete floor was poured inside, blocking moisture evaporation. With no place to go, trapped humidity migrated deep into the masonry. These interventions only accelerated the erosion of the lower parts of the monument.

After the downfall of Hussein, removing the cast concrete floor became a priority. World Monument Fund (WMF) and the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), pulled it up and explored the depth of the Ishtar Gate. They were not able to reach Koldewey’s levels, as Babylon had become, so to speak, a floating city on a lake of groundwater sitting mere centimeters below.

Later, in the summer of 2016-2017, the WMF and SBAH made another section on the western side of the Ishtar Gate, hoping that groundwater levels in the summer would be low, but they discovered underground water 150 cm below the floor, and an intact mušhuššu relief swimming up to its neck in groundwater.

Figure 3, The Mushkhushu is swimming in the water 150 cm below the ground, 2016, credit: WMF

In July 2023, WMF and SBAH began large-scale replacement of Ishtar Gate’s inappropriate modern infill bricks and their cement-based mortar. Excavations along the masonry facades meant to find the depth of these modern replacements to calculate costs for substituting in more sympathetic brickwork. Surprisingly, in some locations, the replacement continued 250 cm to 300 cm below the former concrete floor level, and the groundwater level was now below that. The mystery of why the infills were so deep was found in the SBAH’s archive. Only one paper mentioning that in 1958, a team from the SBAH, headed by Salem al-Alusi, with Kadhim al-Janabi and Najib Kiso, removed the dragons and bulls from the lower eastern side of the Ishtar Gate for the purpose of maintenance in the SBAH laboratories. But that created another question: why were the reliefs not returned to their places after their maintenance and why were they not in SBAH’s stores? So where did they go?

A piece of the riddle happened in 2019. Wahbi Abdel Razzaq, a retired SBAH archaeologist, who had an important role in the project to revive of Babylon, told me, “The SBAH removed parts of the masonry from below and reinstalled the dragons and bulls, on top of the Ishtar Gate.” Mr. Wahbi did not explain to me the details, which seemed strange to me at that time.But the historic photos of Babylon explain to us the process clearly and provide the final clue to understanding what happened. Photos taken in the 1950s show that the level of the excavated intact parts of the Ishtar Gate found by the Koldewey, and later Iraqi missions, show it was not that high, but rather lower. Mr. Wahbi’s words were correct. That is, in reflection of the masonry damage suffered on the west side, the lower parts being affected by rising damp on the east side were raised to be at the top of the Ishtar Gate.

Figure 4, before the animals were moved to the top of Ishtar gate from the bottom, 1950s, credit: SBAH

Figure 5, after the animals were moved to the top of the gate from the bottom, 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

The strange thing is that despite our descent to more than three meters underground, the groundwater did not emerge before reaching 26.3 MASL! Which indicates a significant decrease in groundwater levels in Babylon compared to the year 2016. This is positive for those wishing to carry out archaeological excavations within the site of Babylon. On the other hand, this matter is a serious indicator that the groundwater levels in Babylon, which is in the middle of Iraq are witnessing a widespread and accelerating decline.

Figure 6, during the excavation process, 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Recently, the Water Resources Department provided me with the water levels of the Shatt al-Hillah, during the past seven years. The water level had decreased by about 2 m from 28 MASL in 2020 to 26 MASL in 2023. The result is a decline in groundwater levels in Babylon because the groundwater is mostly fed by the river. Especially after many of the neighboring upstream countries took an offensive stance to ensure that their people get enough water at the expense of Iraq’s water shares, ignoring international treaties related to the regulation and use of water.

As the Shatt al-Hillah continues to shrink, groundwater has become a major source of water for farmers after river water levels decreased or dried up. This was confirmed by Omran Nahr, who lives in one of the villages adjacent to Babylon and works in drilling wells. Nahr says, “During the last seven years, my business started to boom, to the point that I abandoned the manual method of digging wells and bought a machine for digging wells.” According to Nahr’s opinion, the groundwater level in the villages surrounding Babylon was reduced by about 3-4 m. As for southern Babylon, especially in the villages surrounding Borsippa around 20 km to the south of Babylon, it decreased by 8 m. “I used to dig 10 m to reach groundwater, but now I need to dig around 18 m”.

This is an indication of the beginning of the depletion of groundwater, which represents a major economic and environmental threat, especially in light of the major climate change crisis that is afflicting Iraq, in turn, will lead to a decline in crop yields, and it is expected that the current trend represented in Iraq will continue. Hotter, drier, and a large water deficit for decades, which will reduce the country’s domestic food supply and turn the land into salt fields.

Figure 7, the land turned into salt, the area south of Ninurta temple in 2023, credit: Ammar Al-Taee

Close

Close