The Myth of the Working Mother

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 21 June 2013

21 June 2013

The question of what happens to children whose mothers go out to work has generated interest and worry over the years, and is one of the many questions that large-scale longitudinal data help us answer. So when the Campaign for Social Sciences asked me to present alongside David Willetts, Polly Toynbee and Prof Diana Kuh at the launch of the Making the case for longitudinal studies booklet, I chose this topic. I presented a series of research results by several authors, covering several generations. By looking at the findings together, we’re able to make more sense of the results than if we looked at any one in isolation.

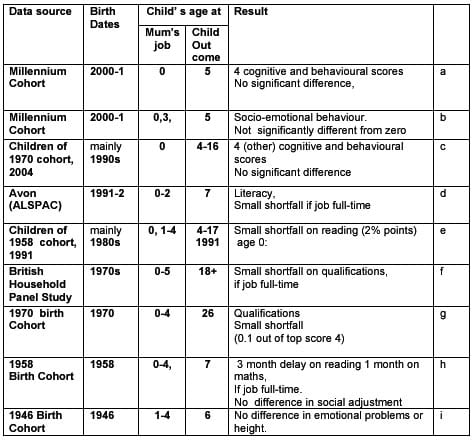

I have assembled (now) nine reports on evidence recording mothers’ employment in their children’s early years and then following the children to an age where they were old enough for their development to be rated. There are various different indicators of the children’s wellbeing or academic achievement, which have been taken at a range of ages from 5 upward. These findings are best summarized in the table below, with the most recent studies listed first.

The association of mother’s employment with a preschool child and outcomes for children at a later age: estimates from UK longitudinal sources.

The latest results come from two investigations on the children in the Millennium Cohort Study, born in 2000-1, which is the fourth in a long line of national birth cohort studies. It precedes the cohorts born in 1970, 1958 and 1946, which appear progressively lower down the table. In addition, the table includes evidence from:

- two studies of the children of the 1970 and 1958 cohort members (assessed in 2004 or 1991)

- a study of the Children of the 90s, who were born in 1991-2

- a subsample of young people from the British Household Panel Study born during the 1970s.

For babies born in 2000 in the UK, employment of their mothers has become the norm rather than the exception, thanks to increasingly generous maternity leave and improved options for child care. There was no significant difference in children’s development in the contemporary investigations of children assessed in the 2000s, adverse or otherwise, between those whose mothers were employed in their first year and other children, allowing for other things, such as mother’s education. As we look at earlier generations of children born between 1958 and 1991-2, there are significant estimates of shortfalls in academic attainment (though not emotional adjustment) found in several studies, particularly if the mother was in full-time employment during her child’s preschool years. Some of these results have fuelled folklore about the dangers of mothers working. The earliest study listed did not report academic outcomes, but found nothing else adverse at age 6.

However, one cannot be certain that the absence of significant findings in the 21st century studies means no child is harmed by any maternal employment. We do not yet know how these children will fare through adolescence, or that the mothers who stay at home are a perfect comparison for what would happen if the working mothers hypothetically stayed at home, and vice versa. It seems safe to argue, though, that worries about the working mother harming her children can be put to rest if we consider how the environment surrounding the balancing of work and life has changed. Not only have there been changes in maternity leave, employment flexibility and childcare provision, but the private and public policy framework has also been moving towards a greater role for fathers sharing the adaptations to work hours and employment.

It has been surprising how many people still assume working mothers feel guilty — I would hope this review can ally fears, but it should not endorse complacency. Working parents often need support for juggling roles, and they should feel entitled to it.

References

a) Hawkes, D. and Joshi, H. (2012) Age at motherhood and child development: evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study. National Institute Economic Review 222(1), R52-R63.

b) McMunn, A., Kelly, Y., Cable, N. and Bartley, M. (2011) Maternal employment and child socio-emotional behaviour in the United Kingdom: Longitudinal evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. Article first published online: 10 January 2011.

c) Cooksey, E., Joshi, H. and Verropoulou, G. (2009) Does mothers’ employment affect children’s development? Evidence from the children of the British 1970 Birth Cohort and the American NLSY79. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 1(1), 95-115.

d) Gregg, P., Washbrook, E., Propper, C., Burgess, S. (2005) The Effects of a Mother’s Return to Work Decision on Child Development in the UK. The Economic Journal 115(501), F49-F80.

e) Verropoulou, G. and Joshi, H. (2009) Does Mothers’ Employment Conflict with Child Development? Multilevel Analysis of British Mothers born in 1958. Journal of Population Economics 22(3), 665-

f) Ermisch, J. and Francesconi, M. (2012) The Effect of Parental Employment on Child Schooling. Journal of Applied Econometrics. Article first published online: 20 January 2012.

g) Joshi, H. and Verropoulou, G. (2000) Maternal Employment and Child Outcomes. Occasional Paper. London: The Smith Institute.

h) Davie R., Butler, N. and Goldstein, H. (1972) From Birth to Seven: The Second Report of the National Child Development Study (1958 Cohort). London: Longman in association with the National Children’s Bureau.

i) Douglas, J.W.B. and Blomfield, J.M. (1958) Children under five. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Close

Close