Do people change their political ideology when they lose their job? If anything, they move to the left

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 16 August 2019

16 August 2019

By Dingeman Wiertz and Toni Rodon

What happens to citizens’ political preferences when they are confronted with economic hardship? This longstanding question has recently attracted renewed attention in the wake of the Great Recession.

Nonetheless, many matters remain unresolved. For example, which types of preferences are affected? Are we mainly talking about views on concrete policy issues and politicians’ approval ratings, or are more deep-seated convictions such as political ideology also influenced? And are all people equally affected by experiences of economic hardship, or do such events elicit a bigger response from some groups than from others?

In a recently published study, we take these questions to the data. We utilise Dutch panel data over the period 2007-2016 to study whether people adjust their left-right ideology in response to job loss and unemployment. Making use of the LISS Panel, we track labour market states and political ideologies for more than 7,000 individuals, whom we observe on average five times each.

Our focus on job loss and unemployment reflects that these are disruptive life events that are far-reaching enough to possibly evoke shifts in political preferences, while still affecting large swathes of society. The latter is especially true over our study window (2007-2016), which comprised a recession featuring multiple years of negative growth and a tripling of the unemployment rate.

Whether people will adjust their left-right ideology when they lose their job is by no means obvious. After all, political ideology is often portrayed as being deeply rooted in early-life socialisation processes. According to this school of thought, ideological attachments would be largely immune to changes in economic circumstances later in life. Yet, others insist that ideological convictions remain “malleable” during adulthood. If we follow that argument, and take into account the centrality of work in people’s lives, job loss may well trigger people to revisit their ideological beliefs.

But even then, it remains unclear whether people would become more left-wing or more right-wing upon losing their job. Standard political economy logic postulates that job loss alters what people stand to gain from redistribution and social protection as advocated by the political left. However, job loss may also give rise to other forces. For example, it is well-documented that economic adversity may intensify hostility towards immigrants – a sentiment that is usually associated with the political right. Indeed, as far as the Netherlands is concerned, the success of Geert Wilders’ right-wing populist party has regularly been linked to the economic turmoil taking place over the past 15 years.

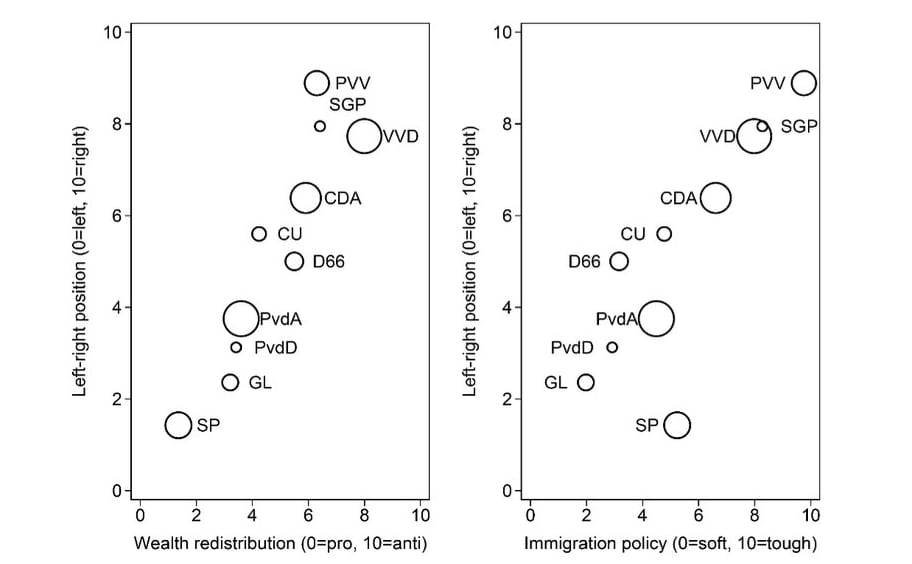

As further background to our study setting, Figure 1 illustrates the ideological left-right positioning of political parties in the Netherlands, alongside their views on redistribution and immigration. As can be seen, parties’ views on these themes are closely linked to their left-right ideology. This makes left-right distinctions clearly visible to Dutch citizens. In line with this argument, recent evidence confirms that the Dutch are very used to thinking in terms of left and right when it comes to political life. All of this goes to show that left-right distinctions remain highly relevant in the Netherlands.

Figure 1: Parties’ left-right positions and their views on redistribution and immigration

Note: Data are from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey. The circles represent average scores over the period 2006-2014, with their size corresponding to the average vote share of each party across the general elections of 2006, 2010 and 2012.

What do we find? Overall, our analyses underscore that left-right ideologies are highly resilient, exhibiting a strong degree of stability over time, even when people are exposed to impactful events like job loss. However, it would be wrong to conclude that political ideologies remain entirely “frozen” when people lose their job. Instead, we find that people tend to revise their ideology – at least in the short run – slightly towards the left upon losing their job.

As far as there are forces at play that push job losers to the right of the ideological spectrum, these forces appear trumped by other pressures that pull job losers to the left. Indeed, while we do observe many people who revise their ideology to the right during our study window, these rightward shifts do not seem directly driven by job loss experiences. This finding aligns well with other recent work suggesting that the success of right-wing populist parties is primarily fuelled by fearsof economic hardship, as opposed to actual experiences of economic hardship. If anything, actual hardship seems to first and foremost trigger a leftward ideological shift.

Although this leftward shift is small (0.2 points on a 0-10 left-right scale) and eventually dissipates as time goes by, it masks a great deal of variation in how people respond to job loss. For many people, job loss has hardly any impact on their ideology, yet for important minorities, job loss is followed by substantial ideological adjustments. These divergent responses are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Variation in the effect of job loss on left-right ideology

Note: These graphs present predicted left-right scores based on regression models that allow the influence of different labour market transitions to vary across individuals. Whiskers depict 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2 demonstrates that job loss triggers a bigger leftward shift when it represents a more disruptive life event. That is, when job losers have to swallow a bigger dose of economic hardship (panel A), when they have fewer financial resources to cushion the shock (panel C), and when they are more cynical about their economic prospects (panel D). There is also evidence that job loss has a bigger ideological impact when it comes as a greater surprise (panel B), but this factor appears less consequential. Be that as it may, Figure 2 reveals important variation in how people politically digest economic shocks.

To put our findings into perspective, it is worth pointing out that the ideological effects of job loss that we observe are not mirrored by an increased likelihood of voting for left-wing parties – at least not during our study window. The potential reasons for this are manifold. For one thing, voting is ultimately only partially ideology-driven and possibly also strongly influenced by who is currently in power. Moreover, aside from its impact on political preferences, economic hardship can have important additional effects, such as alienating people from politics or making them withdraw from public life more generally.

Going forward, it will be fruitful to jointly investigate these effects. That said, political ideology also remains interesting in its own right, as a thermometer of undercurrents in the electorate that may end up shaping the political landscape in the longer run.

This blog first appeared on the LSE European Politics and Policy Blog

Close

Close