Until the DFE understands curriculum its well-meaning pilots will run off course

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 7 August 2018

Arthur Chapman and Sandra Leaton Gray.

Colleagues at the UCL Institute of Education were very excited a few weeks ago to see that the Department for Education had announced funding for a number of school-centred Curriculum Programme pilots worth £2.2 million. These grants aim to support teachers in developing curriculum programmes in science, history and geography. We always like to see practitioner research encouraged, and thinking through curriculum issues is a good way of building a strong basis for professional practice. We were disappointed to see, however, that the DfE in this instance didn’t seem to have done its homework properly in drafting the specifications, which leaves them wanting from an educational point of view.

The main thing that seems to be lacking is a proper understanding of what teacher knowledge means. This is rather ironic given the claim that the project aims to build it. The proposal is designed to reduce teacher workload by developing road-tested materials and an associated pedagogy for teachers to adopt – the materials that the fund will generate must be “knowledge-rich, and have teacher-led instruction and whole-class teaching at their core”. The schools that apply to develop these materials must also subscribe to this orthodoxy. This confuses curriculum – what is to be taught – and pedagogy – how it is to be taught – suggesting that the Curriculum Fund’s custodians have a worryingly shaky grasp of, well, curriculum.

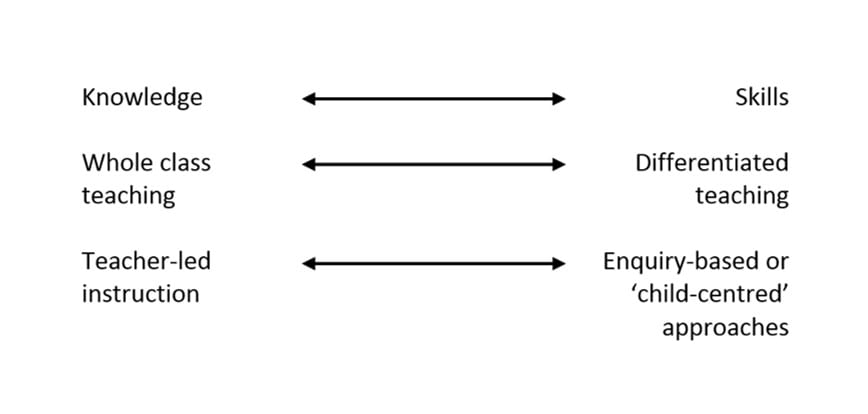

Where they have gone badly wrong is in bypassing the structural principles of the very subjects that they want to support. Their conceptual framing is indicative of a strictly binary, and potentially dangerous, mode of thinking to which ministers in the DfE and their supporters have been wedded for some time:

A key problem with this schema is precisely that it is schematic – much neater than messy educational realities which are conditioned by any number of complexities, including contextual variables, differences in curriculum subjects, and so on. And it’s here where we really feel the need to take them to task.

History is a case in point. Enquiry is key to the discipline of history. As Collingwood argued, historical knowledge-building depends on a logic of question and answer. More important here, however, is the way in which ‘enquiry’ has been used in English history education. Although enquiry (asking questions) involves ‘discovery’ (finding answers) it is not ‘discovery learning’ – in the open-ended and unstructured sense in which that term is often understood by critics of child-centred and constructivist instruction. Enquiry, as it is widely understood in English history education, is a tool for crafting and sequencing curriculum contentso as to give it rigorous disciplinary form and so as to facilitate pupil knowledge-building. Enquiry questions– such, for example, as the question Why was the Norman conquest successful?– are tools that teachers use to organise schemes of work and to plan and sequence content within key stages. Teachers use them to help build knowledge of the past, to develop children’s understanding of history as a subject discipline and, not least, to motivate and engage children to learn about the past.

Enquiry in history, then, is not what the DfE thinks it is. The declaration that enquiry-based approaches in history are invalid in some way is just one example of the muddled thinking underpinning the tender, and highlights the risk that £2.2m is about to frittered on a politically-driven exercise in redesigning the wheel. Let’s hope the independent evaluation the DfE is promising steers the project towards a more fruitful course.

7 Responses to “Until the DFE understands curriculum its well-meaning pilots will run off course”

- 1

-

2

hiesig wrote on 8 August 2018:

Thank you for this. Yes, the category errors / conflation of pedagogy and curriculum is concerning (particularly in a curriculum iniative).

Arthur Chapman -

3

Huw Humphreys wrote on 7 August 2018:

I agree. Apart from being an opportunity missed to engage the profession (and maybe even speak to the Chartered College, now that we have one) this is something that every teacher cares about. We have worked hard as a profession to frame each subject as a discipline, with its own approaches to content, its own “security of knowledge” and its own framing of the type of questions that require their own epistemology. Now we are getting a simplified – over simplified – approach that will do nothing to enhance the status of the knolwedge it seeks to promulgate, presumably. The binary approach is alive and well in the DfE, and the poverty of the thought behind these pilots makes me wonder whether the bright minds of the DfE are still over at the Department for Exiting the EU. Knowledge is important, but it is not served by the way it is accessed, understood and put to use in these pilots. The ongoing obsession with teacher-led instruction and whole-class instruction shows the ideological winning out over all other considerations.

-

4

hiesig wrote on 8 August 2018:

Agreed and thank you for your comments.

I think the lack of appreciation of disciplinarity may perhaps be linked to an interest in cognitive science of a generic type and a reliance on generalist educational arguments (‘cultural literacy’, for example).

Imagine a world where initiatives like this exhibited detailed knowledge of relevant bodies of subject disciplinary literature – such as the corpus of robust teacher knowledge developed through The Historical Association’s Teaching History – and subject specific cognitive science – such, for example, of the work of Sam Wineburg and colleagues in Stanford’s History Education Group.

Arthur Chapman -

5

Graham Holley wrote on 8 August 2018:

I hope the main post will be drawn to the attention of the DfE…

-

6

hiesig wrote on 8 August 2018:

I am delighted to say that the Historical Association have raised the wider issue of conflating ‘historical enquiry’ – a curricular construct – with generalist discovery learning and that the DfE are quoted today on the HA’s website aknowledging that the two are not the same:https://www.history.org.uk/ha-news/categories/455/news/3613/dfe-clarifies-reference-to-enquiry-based-learning.

There are a raft of additional questions to raise, no doubt – not least, where does this leave the status of enquiry in Geography? I expect that the GA will be seeking clarity on this as the HA did.

Whichever way you look at this, it’s far from ideal for clarity about defining features of a costly curiculum initiative to begin to emerge (a) after tender documents have been published (b) in a reactive ad hoc way and (c) in an unofficial form – publication on a subject association’s website.

Arthur Chapman -

7

Steven Chapman wrote on 7 January 2020:

Could not agree more. Having been involved in many Science curriculum developments over many years – including when I was at IoE- this is just ridiculously prescriptive about what good teaching looks like. It’s a long way from the Nuffield and Salters projects.

Close

Close

Well done IoE for flagging up so quickly that the DfE’s latest curriculum initiative is so very flawed. Framing the curriculum with a series of questions does not by itself direct pedagogy; what it does is to establish a readily comprehensible framework for testing its success at the end of the year. Directing how children should be taught the answer is as unwise as it is foolish. Time and again, examinees are stymied by a rephrased question; they need to learn multiple routes to provide solutions and this takes great care to ensure curriculum steps are small and don’t cause cognitive overload.