Revisiting Brian Simon: a major educator in historical perspective

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 14 November 2023

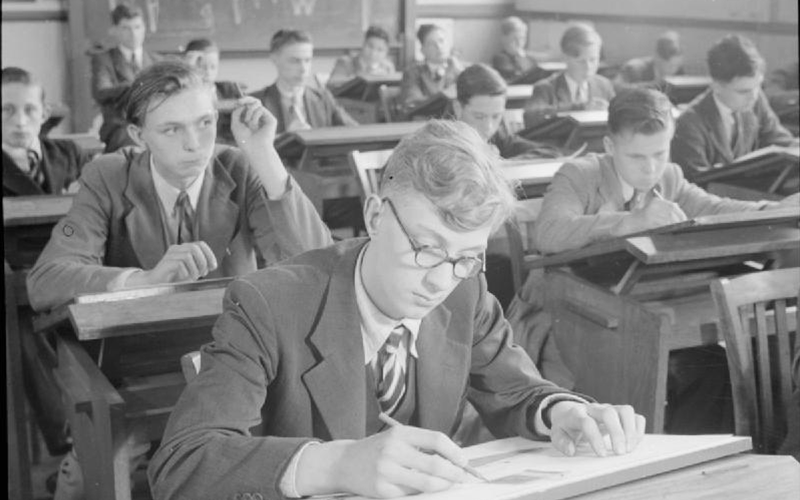

Technical drawing at Tottenham Polytechnic, Middlesex, England, UK, 1944 (Credit: Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer / Wikimedia Commons).

14 November 2023

Student, soldier and schoolteacher, Communist Party activist, and educational academic, campaigner and reformer, Professor Brian Simon (1915-2002) had a distinguished public record in education which was well recognised during his career. His many publications in the history of education, including a four-volume history of education in Britain published in 1960, remain required reading in the field. He had a particular link to IOE as he trained here as a teacher in the 1930s before embarking on his career in education, and his extensive personal archive was donated to IOE after his death.

Yet it is only now, some 20 years on, that we can see him in a more long-term historical perspective as in many ways an underrated figure in 20th century Britain, whose work is well worth detailed consideration in its historical context. His wife, Joan, was also a significant figure in her own right as well as for her contribution to their formidable partnership over several decades.

A new book published by UCL Press – Brian Simon and the Struggle for Education – makes the case for a deeper understanding of Simon’s life and writing. The book has its formal launch this week at the annual conference of the UK History of Education Society, which Simon helped to establish and was an early leader of, along with the International Standing Conference for the History of Education.

Professor Gary McCulloch (centre) and relatives of Brian Simon at the launch of the new book, October 2023. Credit: IOE Communications.

Simon himself was not a philosopher, nor yet a sociologist, but approached educational and political issues as a historian with a deep concern for contemporary reform. His views of past and present informed and reinforced each other so his active support for comprehensive education and his virulent criticisms of the Conservative reforms of the late 1980s in education each drew on his historical perspectives. Nevertheless, they stemmed also from his Marxist theory. No less fundamentally, they were based on his vision of the power of education for individuals and for societies over the long term.

In one way, Simon was significant in relation to socialist intellectuals across Europe, especially in his intellectual affinity with Antonio Gramsci in Italy. Simon was attracted much more to Gramsci’s idea of hegemony than he was to what he regarded as the pessimistic approach to educational change taken by the self-styled ‘new’ sociology of education in the 1970s. His brother, Roger, was a leading populariser of Gramsci in the UK.

As the book demonstrates, Simon hid his light behind loyalty to the Communist Party of Great Britain, even in the 1950s and 1960s when many socialist intellectuals who had joined before the Second World War had abandoned it. By contrast, Simon sought to bring the party together intellectually and to restore its position on the British Left after the damage done in the 1950s, especially by the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary in 1956. Unlike contemporaries such as Eric Hobsbawm and E.P. Thompson, and despite his own deep reservations, he refused to criticise the Communist Party or the Soviet Union in public. His own reputation as a public intellectual has suffered lasting damage due to this loyalty and restraint in what proved to be a losing cause.

In the broader intellectual context of the British Left, Simon has a distinctive and fascinating profile. He had particular ideas about a scientific approach to social change, but has been overshadowed by the intellectuals of the Labour left like Harold Laski, Stafford Cripps and R.H. Tawney, who have already been the subject of substantial biographical works in their own right over the past decade. Brian Simon and the Struggle for Education restores Simon to his rightful position as a figure worthy of detailed attention in his own right, and of further research in future years.

Close

Close