Why the arts should be at the heart of a recovery curriculum

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 16 July 2020

16 July 2020

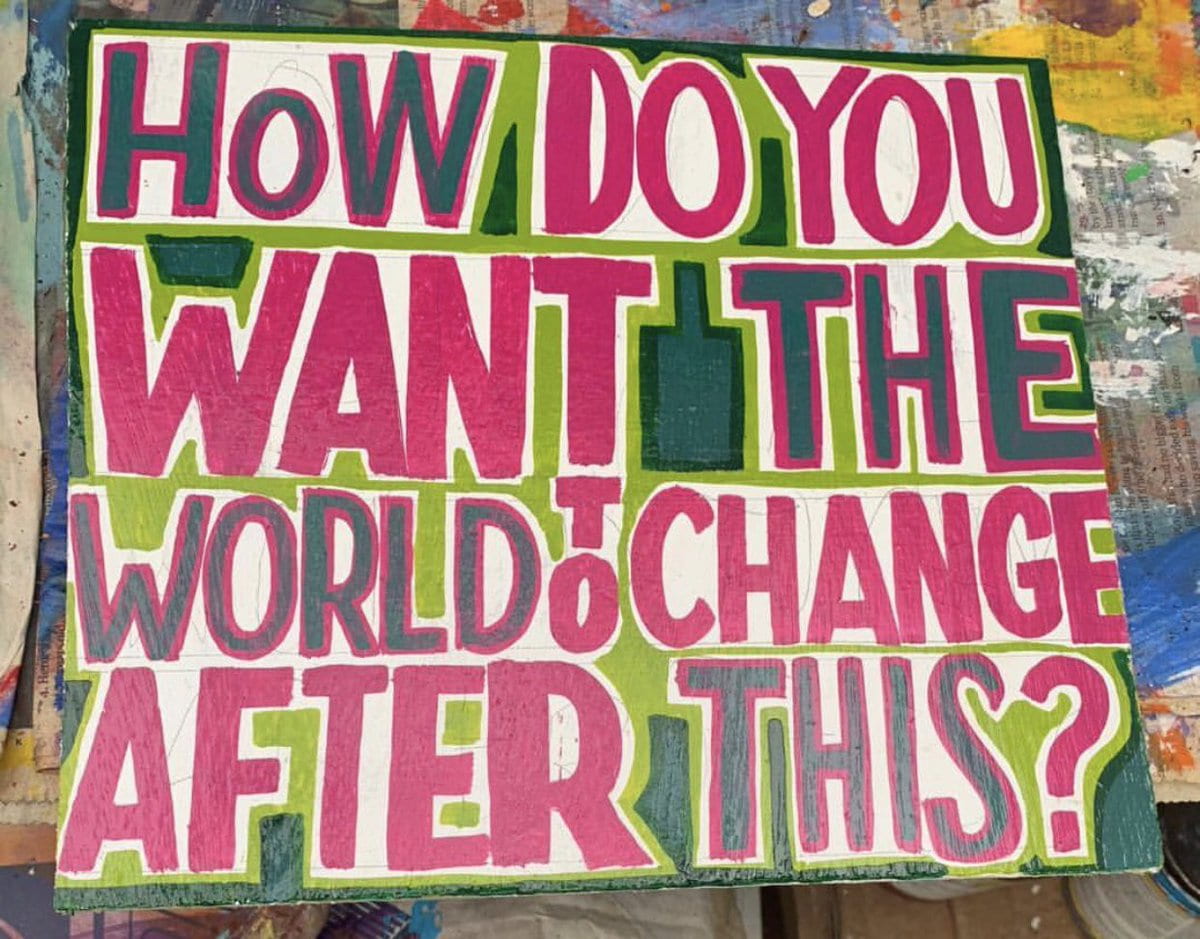

To make up for lost education during the lockdown, the UK government recently advised primary schools in particular to prioritise ‘progress in the essentials’. Consequently, many have voiced concerns regarding the implications this may have for the arts in English primary schools. The artist known as Bob & Roberta Smith has spoken out against the idea of a ‘catch-up’ curriculum, suggesting that this could potentially ‘damage the creative potential of this country, stunting our ability to draw and design the future’.

Many educators and artists believe the arts are more important than ever at this time. They are calling for a renewed focus on the arts in schools as a response to the emotional fallout of the national pandemic.

The government’s announcement echoes the messages which have resounded throughout the pandemic suggesting that pupils – especially those from deprived backgrounds – are falling behind or need to catch up. This catch-up rhetoric often seems to focus exclusively on the core subjects such as numeracy, literacy and science at the expense of the arts. But surely the arts have merit of their own which warrants their inclusion in a ‘catch-up’ curriculum? In fact they could provide what children and teachers need most.

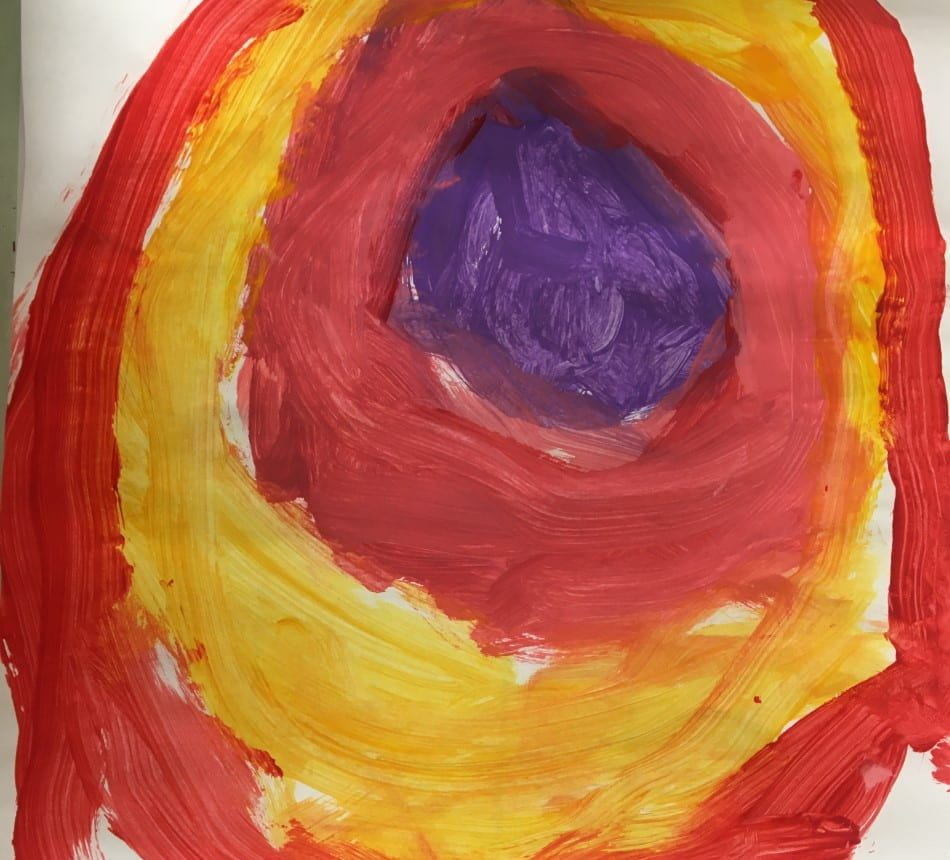

In my own PhD research exploring visual art’s position in the early years curriculum in disadvantaged primary schools across England, the 25 teachers I have interviewed so far have been quick to describe the benefits of the subject for children’s self-esteem. In providing an inclusive and accessible strand of the curriculum, art provides children with opportunities to express themselves and communicate regardless of their background and attainments. This has been demonstrated in my preliminary findings, as one participant commented on how art helps children “to be creative, and express themselves, to express how they’re feeling… and their emotions”.

Additionally, the teachers I have interviewed have almost unanimously indicated the high value the subject has for the children they work with. A further phase of my project will aim to use participatory methods to explore children’s perspectives of their own art education, which will provide further insight into how curriculum narrowing affects children themselves. Ultimately, if our aim in supporting children’s return to full time school is to cement their curiosity and desire to learn, continuing to offer them experiences they hold in high regard – and, put simply, enjoy – would appear to be fundamental.

Considering the upheaval of routine, lack of social interaction and potential loss of loved ones that children have endured over the course of the crisis, some schools are planning to implement what has been termed a recovery curriculum. The idea behind the recovery curriculum is that a focus on relationships, community and space for expression may be key to supporting children through this transition. This reflects the belief that, upon children’s return to school, teachers’ main concern should be reigniting their love of learning so that they can continue their education with enthusiasm. The arts, with their scope for self-expression, collaboration and exploration, are well placed to contribute to fulfilling some or all of these levers for recovery.

A troubling finding from my research has been the suggestion from some participants that the arts were already being ‘squeezed’ from the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) curriculum before the pandemic took hold, a finding which is echoed in other studies of England’s national curriculum. My own participants have variously described the position of visual art in the curriculum as ‘pressured’, ‘squashed’, ‘an afterthought’ and ‘side-lined’. If the curriculum was narrowing as a result of the pressures of policy changes and a heavy focus on accountability and assessment before school closures complicated matters, the implication that these pressures are set to increase come September is disquieting.

The arts could be a great asset in supporting children through these monumentally difficult times. As all children return to school full time in September, we cannot afford to risk disrupting their learning further by greeting them with an impoverished curriculum. A truly broad and balanced approach is crucial to igniting children’s love for learning and making school a safe space for them again.

Follow the IOE’s Helen Hamlyn Centre for Pedagogy (0-11 years) (HHCP) on Twitter

3 Responses to “Why the arts should be at the heart of a recovery curriculum”

- 1

-

2

Dominic Wyse wrote on 17 July 2020:

In my view the risk to the breadth and depth of national curricula is an ever-present danger. Really enjoyed reading this.

-

3

Sam wrote on 22 July 2020:

Not surprisingly, the government are using the crisis to pursue their own ideological agenda. I hope as a society we call them out on it – and refuse it – a bit better than we did with the recession and ‘austerity’…

Close

Close

Thanks for this Helen. I am a passionate Cambridge Primary Review advocate and formerly a High Scope practitioner so I heartily agree!